Updated: The Ugly Truth About Famines

(Above: A malnourished child waits for emergency medical assistance from the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), an active regional peacekeeping mission operated by the African Union with the approval of the United Nations. Photo credit: United Nations).

The real culprit is not drought or poverty, but poor governance

In a local hospital in Mogadishu, a man carries a plastic carpet rolled up in his arms. An aid worker stops him briefly and sees a bundle inside the carpet, wrapped in blue cloth. Inside is the body of the man’s four-year-old son, Abdul Rahim. “I have no money, so I cannot bury my son properly,” he says. “I will just bury him by my tent.” As he walks away, his weeping wife trails behind him, covering her face with her head scarf.

In a refugee camp elsewhere in the city, a 48-year-old man with the spindly body of a boy looks after his last remaining child. Severely malnourished himself, Abdi Ibrahim Yunus has lost five children in three days to measles. He can do nothing more now than watch the precarious breaths of his last child, lying on the floor, covered with a flowered cloth to keep the flies away.

Scenes like these have played out across Somalia in the last few months, as one of the worst droughts in 60 years wreaks havoc on crop and livestock production and causes food prices to skyrocket. This drought-which spurred the UN to declare a famine for the first time since 1984[1]–has affected the entire Horn of Africa, including much of Kenya, Somalia, Ethiopia, Eritrea and Djibouti.

And yet the only areas where the UN has officially declared a “famine” are two pockets of southern Somalia controlled by the al-Shabab militia.

This highlights one of the ugly truths about famines. While a number of environmental, geographic and economic factors must converge to create such a catastrophe, “famine deaths in the modern world are almost always the result of deliberate acts on the part of governing authorities,” writes development expert Charles Kenny.

We live in a world better equipped than ever before to prevent famines. The spread of roads and rail lines allow food to reach remote corners of the globe. Humanitarian agencies have increased capacity and funding to respond to such crises, bolstered by donations that rose from $1 billion in 1990 to $9 billion in 2008. A revolution in telecommunications and geospatial technology makes it faster than ever to identify and respond to pre-famine conditions.

According to one calculation, less than three-tenths of one percent of sub-Saharan Africa’s population was affected by famine in the average year between 1990 and 2005.

But add in endemic corruption and poor governance (or brutal government stand-ins like al-Shabab), and a manageable crisis in other countries becomes a full-blown catastrophe in places like southern Somalia.

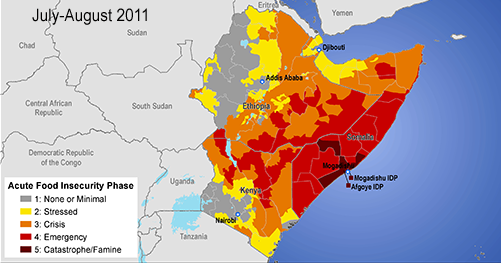

Let’s examine a map of acute food insecurity in the Horn of Africa (figure 1 below).

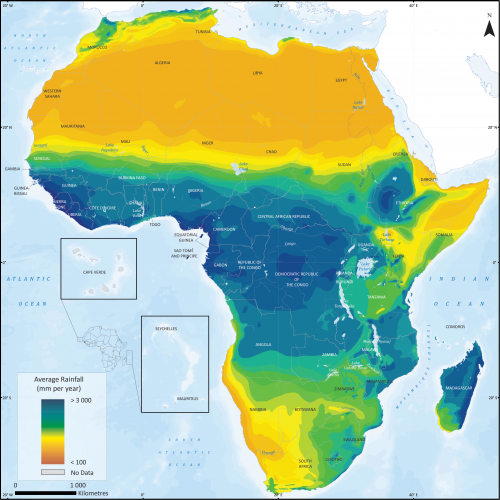

Much of the area surrounding Somalia is in “crisis” or even “emergency” mode, with the two areas around Mogadishu experiencing “catastrophe/famine.” But the climate in the rest of the Horn of Africa is not much different from these two famine zones. In fact, if we examine a map of annual rainfall in the region (figure 2), we can see that these famine areas actually receive more rain than many places around it. In particular, we can see that northern Somalia is more arid than the south (and has fewer rivers, to boot).

The surrounding countries, of course, have not experienced so dramatic a political collapse as Somalia. Nor are their governments fully democratic or perfectly functional. But they have, at least, been responsive to the problems of their citizens in a basic way. The Ethiopian government, in conjunction with the World Food Program, has provided food, seeds, and technical assistance in vulnerable areas over the last few years. Kenya also is supporting relief efforts, while continuing to provide school lunches in drought-stricken areas so that children receive at least one meal a day.

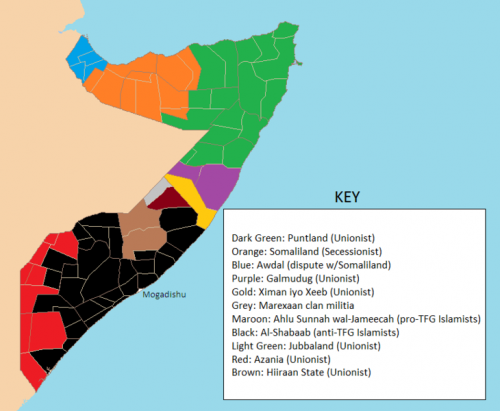

Even within Somalia itself, differences in governance quality affect the severity of the crisis. If we examine a map of internal governing authorities (such as they are) within Somalia today (figure 3), the overlap with the food insecurity map is striking.

In the regions governed by al-Shabab or a patchwork of clashing forces, we see nothing but emergency or famine. Roam northward, particularly west into secessionist Somaliland, and the disaster eases. For years, Somaliland has proclaimed itself independent from the chaos surrounding it, and an elected government provides basic services, security, and a social peace.

Meanwhile, until recently, al-Shabab had banned humanitarian aid from Western groups and was diverting rivers away from villagers towards the land of those who paid them bribes. Perhaps most devastating was the group’s ban on vaccinations in the past few years, which they viewed as a Western plot to kill children. Now, with bodies weakened by starvation, thousands of children are dying from preventable diseases like measles and cholera.

In 1998, economist Amartya Sen was awarded the Nobel Prize for his work in “welfare economics.” In lauding his groundbreaking research on famines, fellow economist Jeffrey Sachs summarized in Time magazine in 1998 what he called “Sen’s law: shortfalls in food supply do not cause widespread deaths in a democracy because vote-seeking politicians will undertake relief efforts; but even modest food shortfalls can create deadly famines in authoritarian societies.”

As we see in Somalia today, even technically lawless countries have areas of good and bad governance, and now the fate of countless Somalis hangs on the quality of the governance wherever they happen to live.

After all, a drought is a natural disaster. But a famine is man-made.

[1]A declaration of famine is usually made by a country’s government, though this requirement was waived for Somalia. However, countries like North Korea, Sudan and Zimbabwe have experienced famine conditions since 1984.

- Categories

- Education, Health Care