‘Market Relationships’ that Stand the Test of Time: A Q&A with TechnoServe’s Simon Winter on progress and peril in Ag development

TechnoServe is a nonprofit that is squarely focused on profits … for farmers and small businesses, that is. The organization works with smallholder farmers, suppliers and big agri-producers in the developing world to boost incomes across the supply chain spectrum. Just last week, it announced the signing of a three-year, $15 million agreement with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which will support an estimated 30,000 small-scale cashew farmers in Mozambique.

Simon Winter, senior vice president of development, has been with TechnoServe for one of its now four-and-a-half decades. Winter is responsible for leading and managing strategy and strategic planning. Among his responsibilities is oversight of TechnoServe’s initiatives around access to finance for small- and medium-sized businesses, and he previously served as regional director for Africa.

I had a chance to talk with Winter about a range of issues in advance of next month’s BoP Summit 2013. Best practices, major roadblocks, and next steps in advancing base of the pyramid strategies in agriculture is one of the summit’s key agenda items.

SA: You’ve been with TechnoServe for 10 years now. In that time, can you tell me how the organization has changed and what that evolution has meant to the farmers and businesspeople it has served?

SW: One key change has been the growing global awareness around food and nutrition insecurity and its challenges for people at the base of the pyramid. This was really heightened during the food price hikes of 2007-2008, which helped put agriculture firmly back onto the development agenda. New resources were made available, and agricultural development, linked to market systems, became more interesting and exciting for people from diverse private sector backgrounds. All of this has had the effect of making it easier for small organizations like TechnoServe to grow our impact.

SW: One key change has been the growing global awareness around food and nutrition insecurity and its challenges for people at the base of the pyramid. This was really heightened during the food price hikes of 2007-2008, which helped put agriculture firmly back onto the development agenda. New resources were made available, and agricultural development, linked to market systems, became more interesting and exciting for people from diverse private sector backgrounds. All of this has had the effect of making it easier for small organizations like TechnoServe to grow our impact.

A second change has been the growing interest by corporations to be more strategic about the potential they have to create business and social value by reducing poverty. That change has created a lot of opportunities for us to engage with them and help shape their agendas in a very pragmatic way, informed by lessons from working at the BoP. And these kinds of partnerships can deliver more sustainable impacts because companies are doing them for strategic reasons, as opposed to traditional corporate social responsibility approaches.

Outside of corporate partnerships, there has been increasing attention to partnership in general. TechnoServe has grown rapidly, but we’re still tiny in comparison to the size of the challenge we’re tackling. We recognize that competing with other organizations in ways that inhibit building collective knowledge is antithetical to our goals. The vast majority of our programs are now implemented in partnership with other institutions, leveraging complementary skills and assets. We’ve also benefited from the rise of networks and convening spaces for organizations like ours – NextBillion, the Aspen Network for Development Entrepreneurs, the upcoming BoP Summit and many others.

Another big change has been the push for greater transparency and accountability among development organizations. We’re not quite where we need to be, but the tide is rising. It’s an opportunity for us because we’ve always been an organization that’s been very thoughtful about accountability, impact and measurement. In a sea of other organizations that haven’t cared as much about these things, it’s a challenge to show our distinctiveness and prove our impact more robustly. As we hope that more resources will become available to support this trend, we can learn better from others and also share our own lessons.

So what has all of this meant to the people we serve? For farmers, there is a greater likelihood today that they will be able to move into a market system framework in a more holistic way that offers them support to address their challenges. Opportunities are increasing to help producers link to suppliers, buyers or sources of finance. We have greater opportunity to catalyze market systems to function more effectively.

Do we think we’re having more impact at a household level than 10 years ago? Not yet. But the chances of creating sustainable change and setting poor communities on a good trajectory are better. While single crop interventions today offer no greater chances for impact, promoting savings can provide the resources for small farmers to invest in a more diverse range of activities.

Today there is a much greater appreciation and evidence that promoting small business growth is critical for supporting poor communities. More organizations understand that helping them develop on a path of growth is a holistic effort, requiring marketing planning, access to mentorship and access to finance, among other elements. But we have a long way to go – we’re still searching for the most successful models for access to finance, and while we’re strengthening networks of mentors and business development service providers, many are not operating sustainably yet. The small and growing business agenda is still nascent and evolving.

SA: TechnoServe is using a new impact measurement system that, according to your annual report, harnesses four main inputs: Participants (how many individuals have benefited from the work), financial benefits (business revenues/jobs/wages), sustainability (or how long these benefits lasted) and efficiency (how much impact is created by each dollar TechnoServe spends). Why the change, and what advantages does it have over the old system?

SW: We needed the change because it was time for an improvement on our old system. As we’ve grown, we’ve realized that getting our results to be accurately measured and auditable is actually the foundation of learning about our successes and failures. The new system has the advantage of being more embedded in our day-to-day work as it relates to our programs. Now we differentiate by types of programs – is it farm-based or business-based? We’ve trained our staff in collecting and verifying the data, and we’ve designed the system to catch possible errors.

SW: We needed the change because it was time for an improvement on our old system. As we’ve grown, we’ve realized that getting our results to be accurately measured and auditable is actually the foundation of learning about our successes and failures. The new system has the advantage of being more embedded in our day-to-day work as it relates to our programs. Now we differentiate by types of programs – is it farm-based or business-based? We’ve trained our staff in collecting and verifying the data, and we’ve designed the system to catch possible errors.

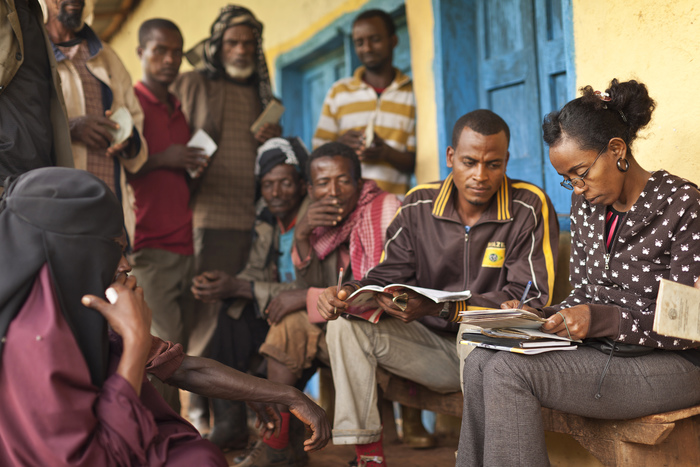

(Left: Record keeping in Ethiopia. Image credit: © Vincent L Long/TechnoServe)

It also sets us up to be better able to interrogate our programs within a sector, or countries, or across countries, and ask more of ourselves about why some things are working better than others. This allows us to have richer discussions about our work and course-correct when necessary. And this measurement system is not a one-off thing – it’s part of a broader effort to get better at managing for impact.

Why do we believe it’s important to look at impact across the organization? We want to know that we provide value for money, and that we’re showing improvement over time. Because we’re mission-driven, we designed the system so it would be in line with our mission and vision. We live our brand through the way we measure our work.

SA: According to your annual report, TechnoServe helped to mobilize $26.2 million in financing to farmers, and $17.4 million in financing to businesses in 2012. What are the main methods for securing this financing, and have you noticed any promising changes or innovations in recent months and years?

SW: The main way of securing financing is helping farmers or businesspeople present their businesses to financial institutions in ways that enable the institution to understand the needs, risks and potential for them getting repaid at a manageable level of risk. This requires a combination of training farmers and businesspeople in financial literacy and financial planning and management so they can understand the financing they need. And this can be complemented by risk management mechanisms such as loan guarantees or insurance. We can help take that package to a financial institution in a way that’s outside the skill set of many farmers or small businesses. At times, we work directly with financial institutions themselves to understand and serve such enterprises.

We’re working to develop a standard set of tools and practices around financial literacy, business forecasting, and other topics. We have a small handful of access to finance specialists and we’re growing that practice. This is a key area of knowledge building and sharing for us. We aim to make this kind of thing more exciting and useful for financial institutions that want to engage clients at the BoP.

In recent years, we’ve seen the rise of impact investing and the recognition that it’s possible to deploy capital in commercial ways and achieve development outcomes as a result. Right now, the key is to make sure the market is there on the demand side. Pipelines are still thin and as a result, capital is sitting on the sidelines. We’re excited to partner with more impact investing institutions to help them deploy capital in productive ways.

Another area where our work has grown is going beyond traditional business plan competitions. We have developed business accelerator initiatives that provide more intensive training and support to meet the needs of the most promising entrepreneurs. We also recognize that there are many potential businesses where entrepreneurs are not yet convinced they should start them. We are actively considering how to leverage TechnoServe’s expertise to find new and unconventional ways to start those businesses.

(Isaac Kirior, (right) chairman of the Tiret Self-Help Group, and member Eusila Lelei tend purple passion fruit vines in the highlands of western Kenya as part of Project Nurture. Image credit: © 2011 Nile Sprague / TechnoServe)

SA: Perhaps related to that, public-private partnerships are a significant focus for TechnoServe. Why is that and how do you seeing it improving the revenues for famers in the long run?

SW: The cost of helping small-scale farmers and small businesses acquire skills and participate in new markets is often greater than private companies are willing to bear. So in many cases, potential opportunities to engage smallholder farmers languish because the private sector can’t do it on its own. When there is a public good rationale that says something is worth investing in, public or foundation funding can help bridge that gap.

Take, for example, Project Nurture, our partnership with The Coca-Cola Company and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation in Kenya and Uganda to help more than 50,000 small-scale farmers to double their incomes from mango and passion fruit. Coca-Cola is benefiting from a small amount of fruit that’s being processed into juice, but most farmers are earning greater value by selling their growing fruit production on the fresh market. Although Coca-Cola is not realizing all of the benefit from this program, they are putting pieces in place for a growing source of fruit – and helping to reduce poverty in the process.

Once these types of market relationships are built and the heavy investment in skill-building has been made, the maintenance costs of sourcing from smallholders should be something that is absorbed in the cost of the goods being sold. Then the change becomes sustainable. The farmers have new markets to sell to and the company has a new source of supply. Public-private partnerships can help us reach that point of continuous improvement and sustainable revenues and income.

SA: I understand TechnoServe has adopted a stronger emphasis on women and youth recently. In what concrete areas are you seeing that focus take hold?

SA: I understand TechnoServe has adopted a stronger emphasis on women and youth recently. In what concrete areas are you seeing that focus take hold?

SW: We’re in the process of standardizing gender procedures in all our programs. We and many others recognize that empowering women is critical for the success of our programs. Our measurement system disaggregates results by gender, allowing us to address disparities. We’ve also developed a set of tools and practices including gender-sensitive program design and tools for our staff to engage women. One example of the type of impact this can have comes from our coffee work in Ethiopia. When we conducted a pilot training program in a socially conservative Muslim area, about 5 percent of the attendees were women. But when we expanded the training and incorporated gender sensitization strategies, some villages reported attendance of up to 30 percent women.

(Above image credit: © 2012 Vincent L Long).

In terms of youth, we’ve recognized alongside other stakeholders that youth unemployment remains a major risk and potential source of instability in increasingly democratic environments. In many countries, job creation is not keeping up with the number of people entering the workforce. Because farming has been an unattractive job for so long, young people are moving to cities and the future of farming is in jeopardy as the average age of farmers creeps higher. One way we’re working to address this is through the Strengthening Rural Youth Development though Enterprise (STRYDE) program in partnership with The MasterCard Foundation. This program aims to assist 15,000 young people in rural areas of Kenya, Uganda and Rwanda through a training program that incorporates topics including life skills, personal finance and employment. STRYDE is taking a systems approach to the challenge of youth unemployment.

SA: You’re participating in the leadership team for the Base of the Pyramid Summit in October, hosted by the William Davidson Institute. (Full disclosure, WDI manages NextBillion). The goal for this team of experts is work with conference attendees to prioritize their recommendations for a post-conference “action agenda,” turning ideas into real-world impact. Why is this sort of process needed to move the sector forward?

SW: A decade ago, there was great excitement about the fortune at the base of the pyramid. I think that promise has not yet been fully realized. There was excitement about the BoP, but with the surge of interest in food insecurity, climate change, shared value and other newer trends, the BoP vision has yet to assist poor producers and to create decent jobs at its fully scaled potential. I think it’s time to step back and say, what do recent trends mean for the BoP agenda? How are we integrating new knowledge in a way that will benefit people at the BoP?

I’m particularly excited about participating in this summit because it’s going to do real work. We’ll use our insights and take this agenda forward to action and to build better partnerships. This will allow us to achieve greater impact at the BoP. This summit is bringing together an excellent combination of thinkers and practitioners. It will be all about real problem solving. If you care about this conversation and its consequences, the BoP Summit is the place to be.

- Categories

- Agriculture, Education