When Human Rights Protests Cost Lives: How can the world fight Uganda’s anti-gay laws without hurting the health of its citizens? The private sector may be the answer

Just over a month ago, Uganda President Yoweri Museveni famously signed a harsh anti-gay bill into law, effectively outlawing same-sex activity in his country and prompting three Western nations to freeze their foreign aid to Uganda, with several more expected to follow suit.

Joining the majority of African countries – and (too) many others around the world – Uganda’s decision to ban homosexuality presents a critical dilemma for the international community: How can we reconcile the country’s unacceptable human rights violations with its dire need for development assistance? Can we make a diplomatic statement without comprising the health and economic condition of Uganda’s most vulnerable people? As one might expect, this nuanced challenge does not have a black and white solution; rather it falls into what I would call a newly minted “g(r)ay area of global development.”

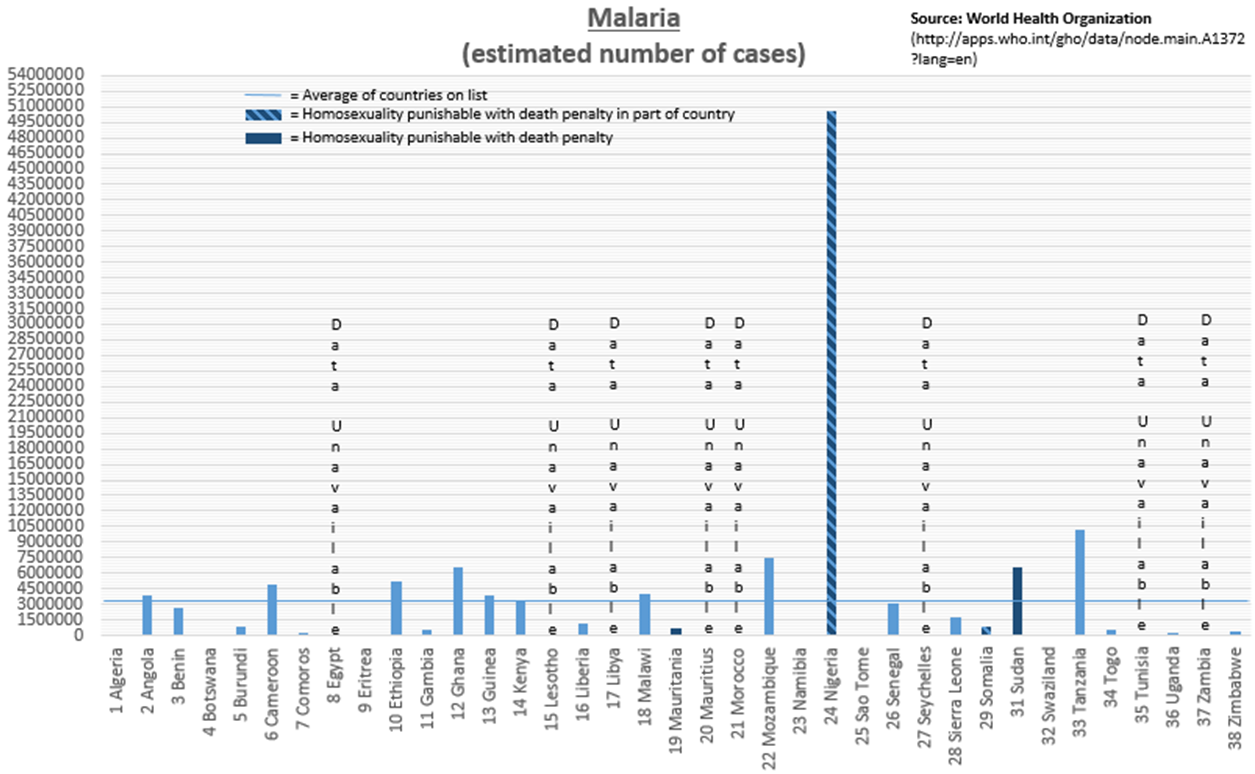

Coming amid a flurry of recent stories linking LGBT rights and global development – from Russia’s anti-gay law that drew attention during the Sochi Olympics to World Vision USA’s decision to continue its discrimination against people in same-sex marriages – this latest anti-gay position reflects a trend among developing countries, especially those in Africa. According to the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association, 38 African nations criminalize homosexuality, four of which have death penalty punishments built into their laws. Reprehensible in principle as they are inhumane in severity, these laws bring with them far-reaching implications about the continent’s overall development, perhaps most notably in their public health outcomes.

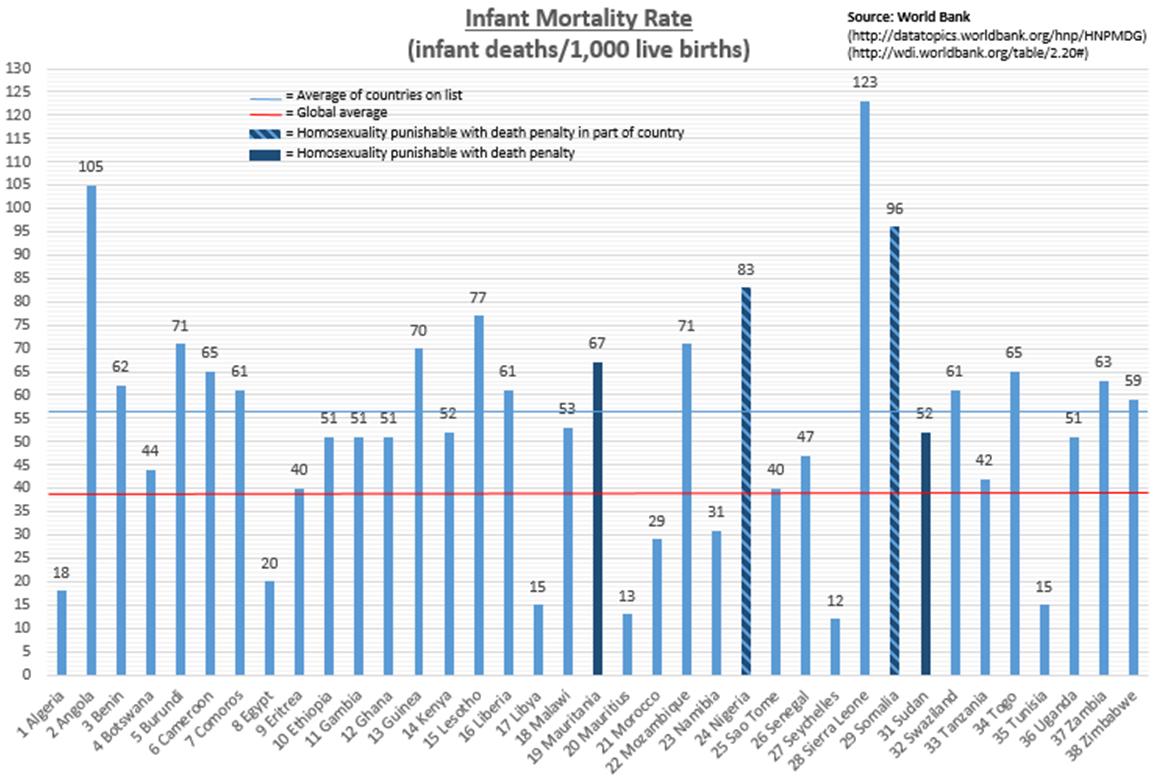

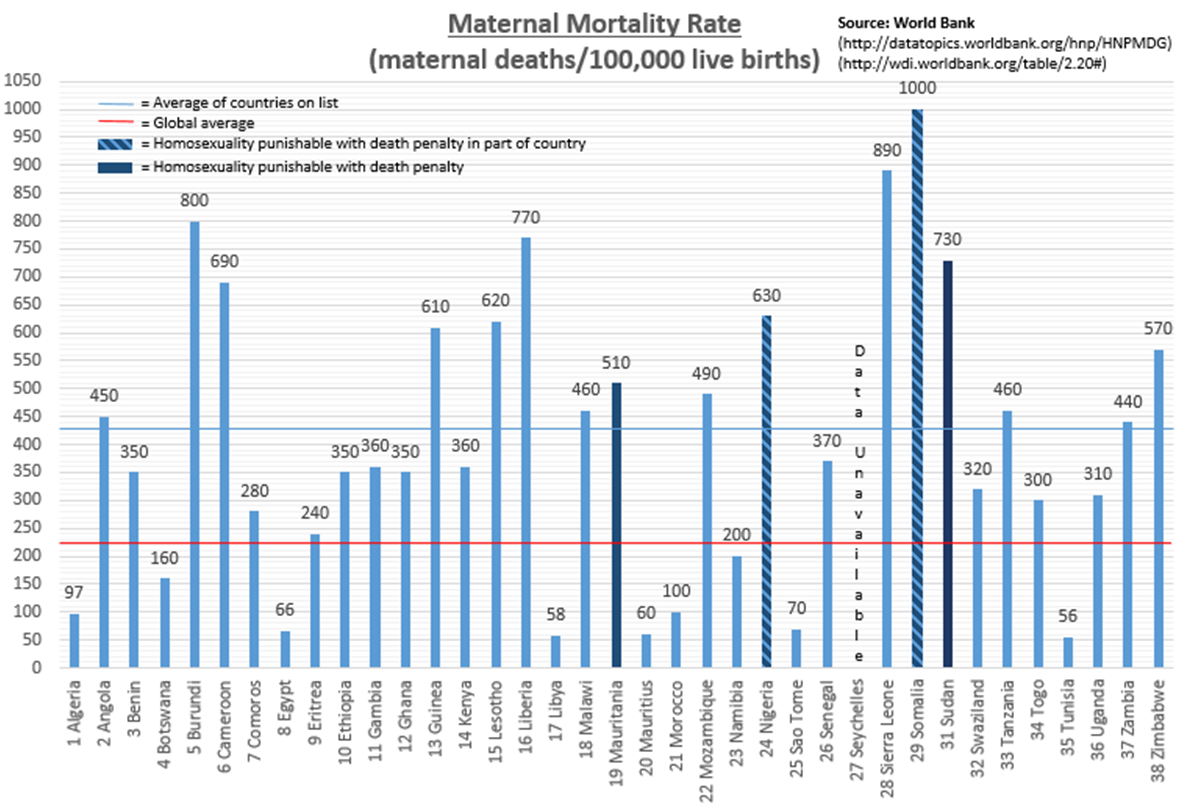

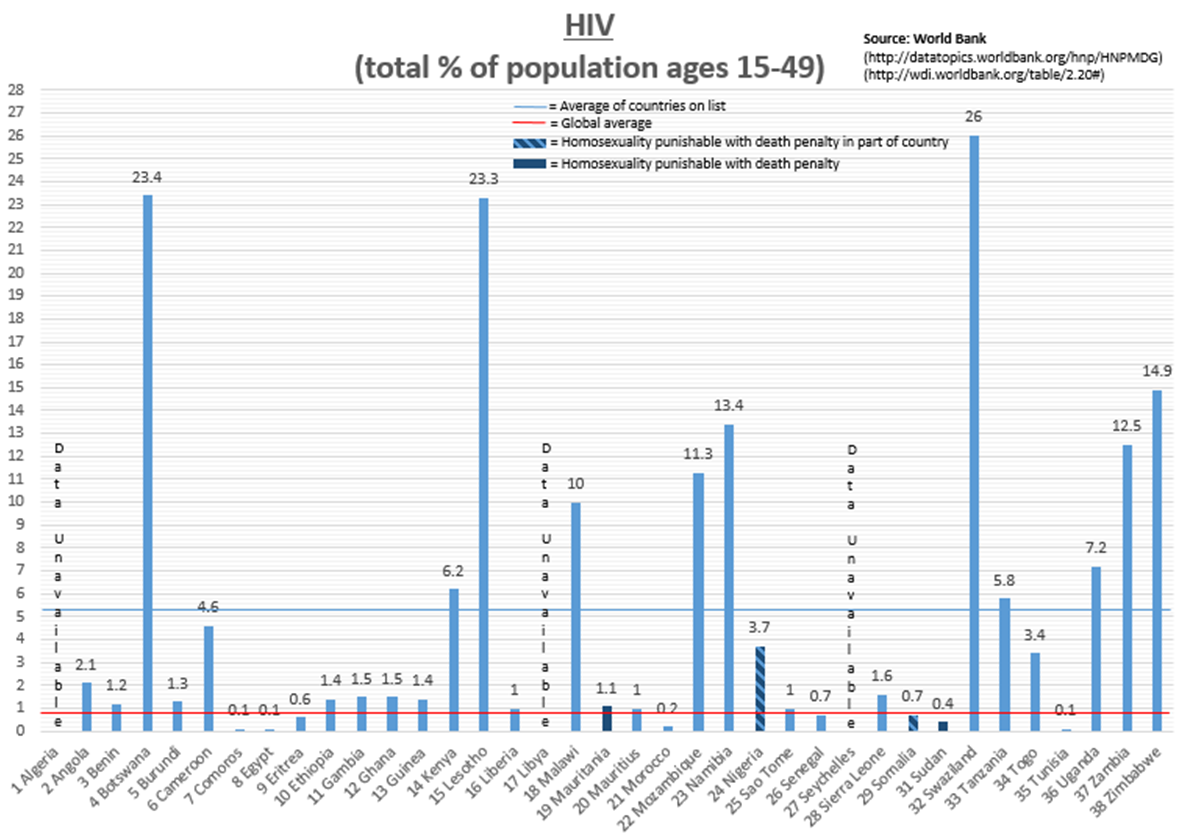

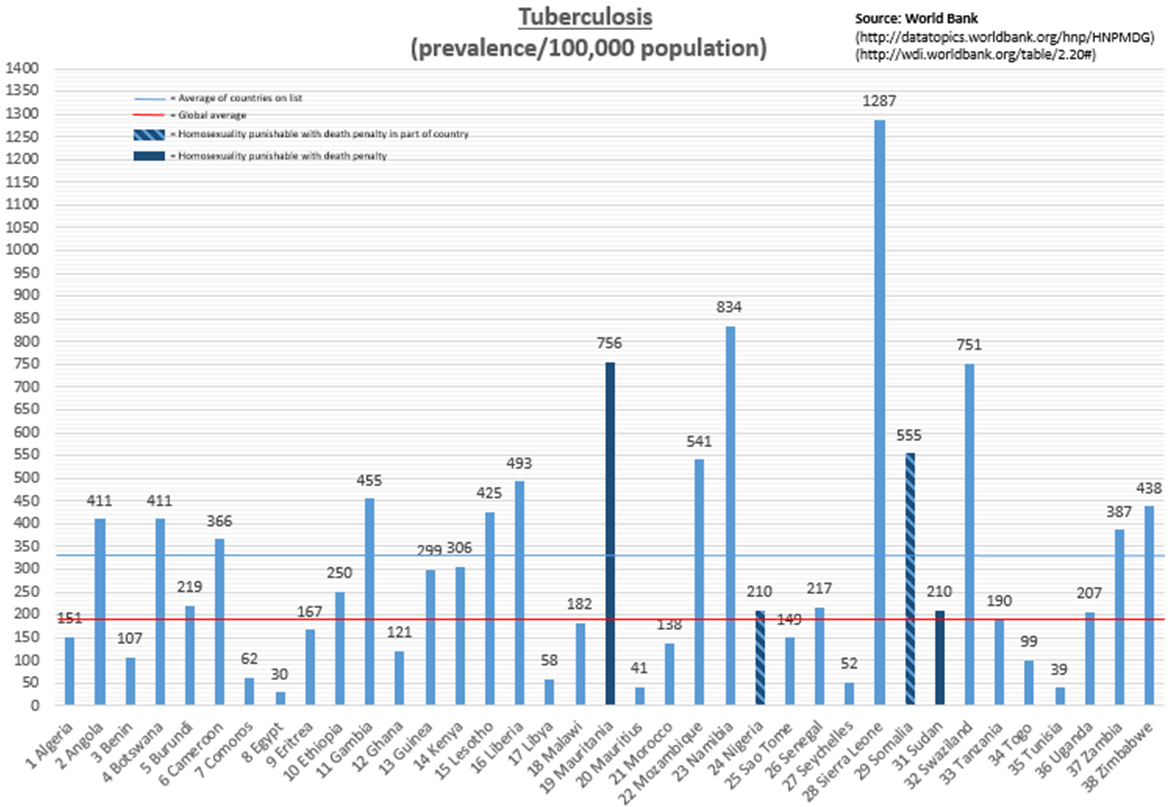

Culling data from the World Bank and WHO, I was able to take a closer look at how these 38 countries perform on the major health issues captured by the UN’s Millennium Development Goals (4: child health, 5: maternal/reproductive health, 6: HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria). Not surprisingly, these countries are doing significantly worse than the rest of the world: nearly 50 percent worse in infant mortality[i], nearly 100 percent worse in maternal mortality[ii], more than 600 percent worse in HIV prevalence[iii] and more than 50 percent worse in TB prevalence[iv] (malaria estimates[v] don’t include the global average).

To interpret a causal relationship simply from these statistics might be a stretch, but the correlation between a country’s basic human rights around sexuality and its public health outcomes is convincing – a conclusion not lost on some development economists like Bill Easterly, who maintains that “the first step (to ending poverty) is not identifying technical solutions, but ensuring poor people’s rights.”

So if gay rights run parallel with health outcomes, what does it really mean when a foreign government withholds bilateral aid in protest of anti-gay legislation? On one hand, freezing funds is an important condemnation of a deplorable law, democratically achieved or otherwise. But on the other, it means that Ugandans benefiting from the assistance hang in the balance.

Consider the case of Norway, one of the countries that halted its aid to Uganda.

Norway provided more than U.S. $50 million in bilateral assistance to Uganda in 2012. Of that sum, more than half went to the environment and energy; education; economic development and trade; and health and social services – all of which disproportionately affect low-income communities and those most at risk of infant and maternal mortality, HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria. This aid was also offered primarily through the public sector, multilaterals and NGOs, with less than 1 percent going to the private sector – a notably low priority.

The private sector comprises a crucial component of Uganda’s health system, with significant reach into high-need communities. According to the World Bank, this mix of physicians, nurses, midwives, clinics, pharmacies and hospitals provides more than 60 percent of Uganda’s health care and 53 percent of its care to people in the lowest income quintile. Families tend to prefer these groups because they are often perceived as cleaner and friendlier than public facilities and more attuned to local needs and customs, thus fostering a sense of loyalty among customers. They also hold the potential for sustainable development that is decreasingly dependent on future donor funds.

In light of this reality, what if Norway reallocated its aid to investments in local health businesses and providers that target families in low-income, high-burden markets? As it happens, Norway – along with Denmark – has already agreed to redirect about U.S. $8.5 million to private-sector initiatives, aid agencies and rights organizations. But what if it committed even more? And what if it brought other countries on board to protest Uganda’s anti-gay policy while supporting a local private sector that already plays a vital role in getting health products and services to Uganda’s most vulnerable people?

The answer, of course, is unclear. But there are mechanisms in place to find out.

Norway, for one, has established a few funding initiatives focused on private-sector development, as well as the Norwegian Business Council in Uganda. Likewise, as the United States reviews its foreign aid policies in Uganda, it could consider further tapping its Development Credit Authority, which has provided more than U.S. $3 billion in credit to private-sector borrowers in the developing world, including U.S. $7.5 million devoted exclusively to Uganda’s private health sector. And, after postponing a U.S. $90 million loan to Uganda’s health system in response to the anti-gay law, the World Bank could advocate for increased investment in its Health in Africa Fund, which is mobilizing U.S. $1 billion in resources to support “socially responsible and financially sustainable private health companies.”

It is an unfortunate truth that our 21st century world still plays host to dozens of countries that would sooner legislate against homosexuality than, say, implement policies aimed toward economic growth and improved health outcomes. But Uganda’s recent decision reaffirms that this stance is indeed a reality with which the international community must contend. It is critical that the world demonstrates its diplomatic disapproval without abandoning its health and development goals – and the at-risk men, women and children they support. Rechanneling investments in the private sector could strike that intricate – and never more important – balance.

- Categories

- Health Care