Moving Health Commodities in Africa: Private sector transport for public health systems

Editor’s note: VillageReach recently completed this assessment of the Mozambique Ministry of Health’s (MISAU) transport fleets and logistics practices to identify key opportunities for improvement. The assessment also considered the unique business environment and practices of commercial transport operators to determine if MISAU’s freight transport and distribution requirements could be outsourced to the private sector. The research coincides with the ministry’s investigation of outsourcing its transport in order to improve operating efficiency, access higher-quality resources and vehicles, gain access to innovations developed in the private sector, and free up internal resources to address core health systems functions. The author is VillageReach’s director of strategic development and head of private sector engagement.

Across sub-Saharan Africa, tens of thousands of health centers serve rural communities. Many of these facilities are located at considerable distance from district and regional storage centers that supply the health centers. Well-managed transport is critical to the successful operation of this supply chain that originates at national stores. But for most health systems in the region, current practices and resources are inadequate to provide reliable and sustainable transport to support the distribution of medical commodities.

Mozambique is no exception. Freight transport fleets are a critical component of health care, owing to the vast geography and great travel distances in the country. The Ministry of Health oversees the use of government vehicles at both the national and provincial levels. In rural districts, however, there are few formal fleet management practices, in part owing to the chronic shortage of functioning vehicles. It is common to see vehicle graveyards at health facilities, due to shortages of parts, lack of maintenance and other factors; in some cases, these expired vehicles may not have moved in years.

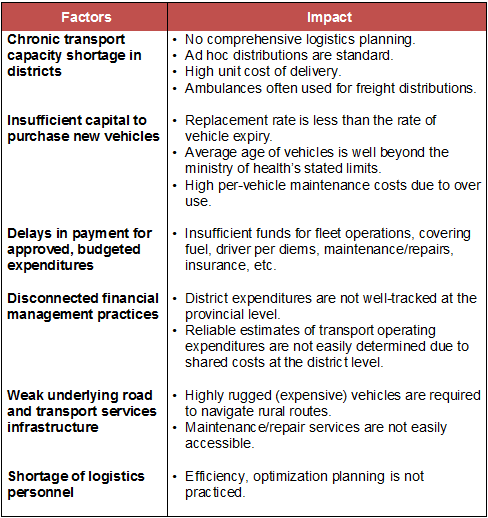

Many factors contribute to the often chronic shortages of vehicles. We observed that MISAU’s transport function is limited in capacity and performance primarily due to the key factors in the chart below.

As a key component of our Dedicated Logistics System (DLS) directed at improving vaccine access and delivery in Mozambique, we own and operate vaccine distribution vehicles in each of four provinces. The work covers distributions to more than 400 rural health centers, serving a population of approximately 8 million. We retain responsibility for all aspects of the logistics planning and fleet management for these vehicles and work in close cooperation with each provincial health authority that has some transport capacity of its own. Our use of dedicated logistics vehicles to deliver vaccines has resulted in significant improvements in the availability of vaccines at health centers, and documented reductions in cost of delivery.

But making transport more cost-efficient and reliable meets only half of the challenge. It also must be sustainable; hence our current work looking into commercial transport as an option for outsourcing from the Ministry of Health.

MISAU may well have one of the best opportunities in the region to leverage public-private partnerships in the next decade; Mozambique has a burgeoning extractive industry and is expected to play a critical role in supporting trade expansion in southern Africa. An anticipated result is increased capital to fuel the creation of more small- and medium-size enterprises (SMEs), including those engaged in transport. As rural development progresses and communities become more connected, the creation of more small-scale regional and district-based transport carriers will help address the growing demand for freight transport.

We are seeing this growth firsthand through the social enterprise we co-founded, VidaGas, that supplies propane fuel to rural health centers for refrigeration, lighting and sterilization. The provincial health administrations in three northern provinces currently outsource much of their energy requirements to VidaGas rather than assuming responsibility for this function themselves.

Because of the high capital costs and technical complexity of running a logistics function, the Ministry of Health should also consider applying this outsourcing principle to transport.

This development could have far-reaching benefits for ministries of health that typically have under-capitalized transport functions, limited logistics expertise and insufficient vehicles and storage facilities to reach all rural communities.

(A rural road in Mozambique, right, gives a glimpse of some of the problems involved in moving health commodities.)

(A rural road in Mozambique, right, gives a glimpse of some of the problems involved in moving health commodities.)

Our research included these recommendations to help prepare the ministry for external transport support.

1. Update assessment of true fleet capacity within provincial fleets. The evaluation revealed a discrepancy between official fleet lists of the provinces and the number of functioning vehicles available in districts. District audits would reveal true current transport capacity for an entire province, and also expose prevailing practices in the use of vehicles.

2. Benchmark vehicle use. To consider outsourcing the transport function to the private sector and evaluating its competitive benefits, a more accurate benchmarking of the current use of vehicles, the attendant costs and overall performance is needed.

3. Establish key performance indicators for optimal fleet operation. These core indicators and regular dashboard reporting would enable proactive logistics planning, support goal-setting and improve performance over time.

4. Manage district fleet assets independently. District health managers do not have responsibility for the vehicles used for distributions. Providing districts with ownership and full decision-making responsibility over their vehicles would enable greater accountability and performance evaluation.

5. Conduct district logistics audits. Independent audits of current logistics practices, including route planning, vehicle use, etc., would help support either future requests by MISAU for additional vehicles it will own and manage directly, or outsourcing the transport function to the private sector.

6. Establish logistics management positions and supporting training. There is a severe shortage of professionally trained logistics managers for all levels of MISAU’s supply chain. Identifying these roles is critical for both direct management of an internal transport function and for outsourcing.

7. Streamline budgeting and financial approval processes. To enable greater accountability at lower levels of the health system supply chain, managers require greater funds management flexibility and shorter response times to requests for financing.

8. Establish private sector engagement practices to support outsourcing. Establish base-minimum performance levels and monitoring practices to develop data in support of ongoing evaluations, and establish both performance incentives and responses to deter substandard performance by private carriers.

John Beale is VillageReach’s director of strategic development and head of private sector engagement.

- Categories

- Environment, Health Care