NexThought Monday – Relieving the Burden: The role of microinsurance in financing HIV care

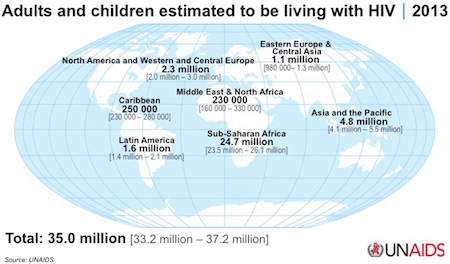

More than 35 million people are living with HIV/AIDS, many of whom live in low- and middle-income countries and are unaware of their HIV status. New HIV infections appear to be on the decline due to greater accessibility and reductions in treatment costs and although HIV cannot be cured, lives can be vastly prolonged using a combination of anti-retroviral drugs.

With the introduction of generic drugs, treatment costs have plummeted from $10,000-$15,000 (U.S.) per person per year in the 1990s to around $115 in 2013 for first-line ART (anti-retroviral therapy) for low- and middle- income countries. About 5.6 million more people are receiving ART treatment than in 2010, yet three in five people living with HIV (PLHIV) still have no access, and the financial implications of an HIV diagnosis remain considerable for low-income populations. Treating the disease is financially burdensome for those without access to government-subsidised and readily available ART, and many patients must pay substantial out-of-pocket expenses for the treatment of opportunistic infections, CD4 count tests and transportation to treatment centres.

To cope with the financial implications of a diagnosis, many families sell vital assets. According to figures from Avert, two-thirds of HIV-affected households in Uganda have had to sell land, capital or property to pay for treatment and 67 percent required financial support from family during treatment. Studies from Zambia and Kenya found that many do not envisage a future for themselves once they are diagnosed and sell assets, expecting their lives will be cut short before feeling the impact of such losses. As HIV treatment is increasingly prolonging lives, many people with HIV are living longer with limited finances to draw on.

In low-income communities, the burden of caretaking of afflicted adults often falls on children, which affects school dropout rates and weakens the educational levels of the population. Women are also disproportionately likely to bear the burden, largely due to cultural conceptions of women’s role as caregivers.

On an economic level, firms and businesses are also affected as AIDS deaths often hit those in their prime working years. With 19 million people unaware of their HIV status and many more not receiving treatment, companies lose the savoir faire accumulated by skilled workers who become sick or die.

On an economic level, firms and businesses are also affected as AIDS deaths often hit those in their prime working years. With 19 million people unaware of their HIV status and many more not receiving treatment, companies lose the savoir faire accumulated by skilled workers who become sick or die.

Countries with HIV epidemics face a substantial loss of human resources such as teachers, health workers and agriculture workers. Further, national savings are often reduced as resources are diverted, all of which can reduce GDP and national development. In some countries, more teachers are dying of HIV/AIDS than are being trained.

This all indicates a real need for effective protection mechanisms to protect the vulnerable and limit the infrastructural impact of HIV.

HIV and microinsurance

Microinsurance is best described as a mechanism specifically tailored to the needs of low-income people to protect them against risk in exchange for affordable premiums proportional to the likelihood and cost of the relevant risk. It can play a role as an HIV risk financing mechanism and alleviate some of the burden on public resources.

To help manage treatment costs, some countries are starting to provide free ART to people with a CD4 count above a specific threshold, yet currently only 8 million of the 14.8 million eligible are on treatment. There is a real gap in financing inpatient care and medication for comorbid/opportunistic infections — as public programmes are often limited to ART treatment, these additional and often substantial costs require out-of-pocket payments. This is important as those with limited access to health care often do not seek medical treatment until symptoms manifest. It is in this gap that microinsurance could provide some helpful solutions to HIV care.

Insurance policies usually exclude HIV but perceptions of the risk of insuring people with HIV are gradually changing with treatment costs lowered and chronic diseases such as cancer posing a bigger risk. The cost of testing and monitoring the statuses of an entire client base is increasingly thought to outweigh the perceived benefits of exclusion.

To manage the HIV crisis, a number of microinsurance programmes have been piloted or implemented.

India

In Salem district, Tamil Nadu state, India, a programme piloted by DHAN Foundation in 2010 aims to protect PLHIV and dependents with health and life coverage. The life cover provides a safety net for dependents in the event of the death of the family member, whilst the health cover provides primary health care and hospitalisation benefits which address the increased health care needs of PLHIV. The programme also offers wage loss compensation when a customer is hospitalised for up to 15 days. The premise of the project is to provide coverage to an entire community — an integrated pool of both PLHIV and general population with normal risk — by way of a mutual fund meaning the risk pool is more evenly distributed, adverse selection is reduced and a healthy portfolio maintained. As of March 2014, the pilot was already successfully covering over 60,000 households.

Kenya

In Kenya, discrimination laws prohibit insurers from demanding HIV tests which incentivises expanding coverage. The HIV epidemic has also hit higher-income segments, suggesting the viability of commercial HIV insurance for these segments. Costs remain an issue for low-income people who can rarely afford private insurance that often costs $150 per year per family — a large sum in a country where almost half the population live below the poverty line. This opportunity has led to the creation of more affordable microinsurance products and encouraged insurers to form partnerships with one another and with social welfare groups to lower costs and increase subscription rates. Whilst progress has been made in terms of the insurance products offered, the supply of microinsurance products for low-income segments has been hindered by various regulatory challenges, such as clients being obliged to pay their premiums up-front instead of in weekly or monthly instalments — which would be a less burdensome solution for many low-income households.

Challenges and barriers

Although the above offer examples of expanded microinsurance coverage, additional examples are hard to come by.

Stigma is largely responsible for a lack of engagement by commercial insurers. Assumptions that covering PLHIV is too risky and not financially viable have perpetuated for years, even though Kenyan and Ugandan companies started to successfully provide optional HIV/AIDS treatment coverage over a decade ago, back when ART costs were dramatically higher. This perception of HIV as costlier than other chronic illnesses is not supported by actuarial data, and risk analysis in fact favours HIV coverage. As the biggest expenditure for PLHIV is on treating opportunistic illnesses, it seems futile to encourage insurers to cover HIV if they are not going to address other chronic diseases such as tuberculosis (a leading killer for PLHIV) as well; the focus should be on incentivising insurance companies to cover an array of chronic diseases.

The SHOPS project, USAID’s flagship private sector health initiative, found that in Nigeria, Uganda, Kenya, Malawi and Namibia, decisions to cover HIV were often determined by national policy. Whilst Kenya’s laws may incentivise expanded coverage, in Nigeria insurers are obliged to refer clients to public sector providers, hindering profitable partnerships with private providers.

Programmes have often failed to move beyond pilot stage because willingness to pay was not high enough. For clients to value insurance enough to part with a premium, they need assurance about the quality of health care they will have access to. Throughout Sub-Saharan Africa, investments have been made in building capacity of lower-level facilities designed to deliver HIV care at relatively low cost. However, many facilities remain sub-standard and benefits are not always effectively communicated to clients. Lack of insurance culture and financial education has hindered scaling of microinsurance programmes and eligible clients do not always perceive the benefits of insurance. Efforts to incentivise insurers are wasted if few potential clients will purchase the product.

Identifying ability to pay is important. The global middle class is increasing and with more disposable income, more people can access private health care. Within low-income populations, there are vast disparities in ability to pay for premiums. Whilst severely at-risk groups (e.g. sex workers and cross-border truckers) might desperately need the protection offered by insurance, they may be unable to pay premiums and must rely on publicly available interventions. On the other hand, mutual schemes for some rural low-income communities, such as Dhan Foundation’s experience in India, can offer affordability to clients as well as relatively low risk for insurers. In reality there are big disparities in suitability and need for microinsurance products in low-income populations.

Partnerships: An area of opportunity

Many low-income PLHIV are priced out of private health coverage as commercial companies often demand high premiums with limited benefits, while public programmes are limited and struggle with the number of people requiring ART. HIV/AIDS response programmes have traditionally been aid-funded by initiatives such as PEPFAR, because of the emergency nature of the crisis when it first emerged but with reduced treatment costs and relative stabilisation of transmission rates, there is a global move towards country-owned responses through partnerships.

(PEPFAR works with partner countries and other key stakeholders in the U.S. and abroad to minimize the impact of HIV/AIDS on women and girls around the world, right. Photo courtesy of PEPFAR)

(PEPFAR works with partner countries and other key stakeholders in the U.S. and abroad to minimize the impact of HIV/AIDS on women and girls around the world, right. Photo courtesy of PEPFAR)

Partnerships offer opportunities to address challenges through financial burden and risk sharing and can incentivise insurers to expand coverage.

Government and donors

Increased domestic funding for HIV responses, as in South Africa, Kenya and Zambia, is vital to strengthening the infrastructure required for microinsurance growth. Governments and donors can finance quality facilities, partly or fully subsidise premiums or manage services normally provided by insurers, such as HIV testing, to make schemes more financially viable. They can lead the implementation of educational schemes for potential clients to reduce HIV transmission and increase uptake of health insurance and, importantly, implement policies that incentivise growth of HIV-inclusive microinsurance.

Social health insurance plans can also strengthen the private insurance market by offering insurers a large risk pool of sick and healthy individuals, limiting the risk of covering ART.

Governments and donors can also assist by supporting actuarial analysis. For example, in Namibia, actuarial analysis from a public-private partnership involving the SHOPS project found male circumcision to be a cost-effective HIV preventive. Now, nine out of 10 health insurance plans cover male circumcision.

Health care providers

Leveraging partnerships with health care providers can reduce costs for insurers. Through such partnerships insurers can negotiate a package of services at a mutually agreeable price and soliciting higher quality treatment can improve health outcomes and ensure less frequent hospital visits — helping reduce costs.

Financial institutions

Financial institutions such as MFIs have an important, mutually beneficial role to play. A significant number of credit defaults are due to health problems, which is an important incentive for MFIs to support microinsurance. DHAN Foundation’s microinsurance scheme profits from the social capital built in earlier programmes, in the form of community organisations that have gained expertise in microfinance services over a long period. Using existing financial infrastructure to distribute microinsurance streamlines the implementation process and reduces costs.

Conclusion

In regions with high HIV prevalence, excluding PLHIV from coverage means shunning segments of a client base whose condition can often be stabilised relatively easily and cheaply. In countries with low HIV prevalence, including PLHIV in insurance pools will have a negligible impact on underwriters’ profit margins. Of course, in high prevalence regions, targeting a client base disproportionately composed of PLHIV would mean high risk in the customer base, so premiums would outprice many. The success of DHAN Foundation’s pilot stems from its inclusion of PLHIV without catering exclusively to them; the product covers an entire community. Further, partnerships are vital to spreading risk to incentivise insurers to expand coverage and ensure that inclusive microinsurance is financially viable.

Microinsurance is not the primary solution to solving the HIV/AIDS crisis but in the absence of universal health care and access to ART, it can play a vital role in managing existing cases, providing ART for those with limited access and addressing hospitalisation needs. Effective financial mechanisms such as insurance can help safeguard individuals from poverty cycles, in turn protecting the infrastructural development of emerging economies.

Julia Graham is the knowledge and advocacy coordinator at Microinsurance Network, Luxembourg.

- Categories

- Health Care