‘Frightening Hype’ in Impact Investing and Other Ways to Move the World

Impact investing, with its promise of financial and social returns, started out as a way to unlock large amounts of private sector capital for for-profit social enterprises, allowing them to grow more quickly. Now, we’re seeing a dissonance – especially in India, where the enormity of the BoP population has lent a fierce emphasis on an enterprise’s ability to scale. Nowhere is that friction stronger than between many social entrepreneurs and the impact investors who purportedly support them. Socially committed for-profit entrepreneurs with business models that don’t lend themselves to an easy financial exit are ignored by the social investment community and isolated from the conversation. Even many of those who fit into the investor mold are facing unreasonable pressure to create returns and scale.

On the investor side, the line between “social enterprise” and “enterprise” is continually blurred as impact investors chase the few exit-possible enterprises making some sort of impact at the BoP. Impact investors are also grappling with what Naren Karunkaran, in a a recent article in The Economic Times, calls a “frightening hype.”

“It has ramifications for India as the country is still recovering from the microfinance bubble that burst, debilitating an entire industry that worked for the poor.”

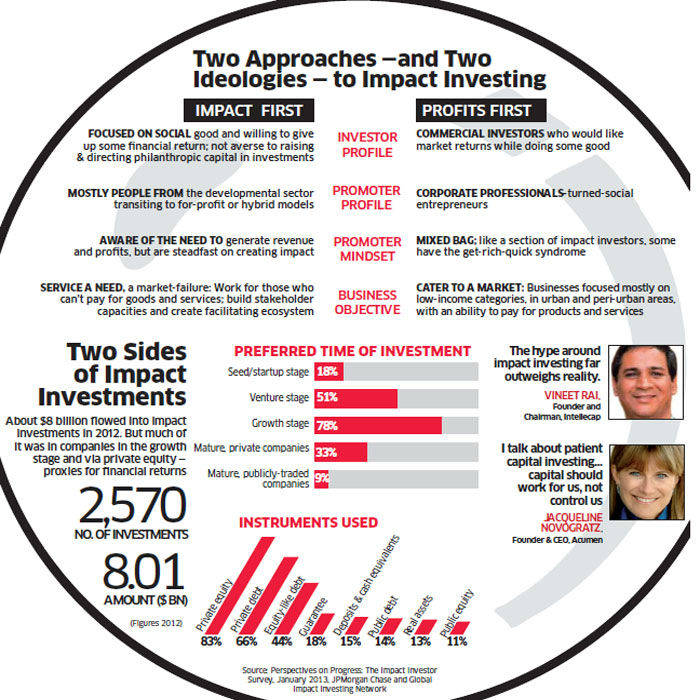

As a result, Karunkaran argues, there is emerging an uncomfortable dichotomy between “impact first” and “profit first” impact investors. This is illustrated further in the following graphic:

Source: Economic Times. July 23, 2013.

That fact is some enterprises are well suited for impact investing – for example, for-profit social enterprises that fill critical supply chain gaps or provide access to low-cost healthcare – playing hugely integral roles in the development story.

However, because of the hype, the overwhelming emphasis on scale, and of course the ever-present white elephant in the room, the question of exit – many social ventures (both for- and non-profit) making deep, meaningful impact on the poor, disrupting ancient, oppressive systems, and empowering the next generation’s leaders, are receiving neither the attention nor the funding they deserve. Disrupting systemic problems that have existed for, literally, thousands of years require deep, holistic approaches – approaches that often need to be subsidized or take non-profit models. However, many organizations that may be more effective as non-profits often feel pressured to go for-profit just to tap into impact investments, while for-profit models making deep impact that might need more time to get their model off the ground sometimes are denied that leeway by investors. In the current high-pressure investment climate, the latter might benefit from starting as a non-profit and transitioning to for-profit later.

If non-profit ventures are able to function well and create deep impact (possibly a more transformational impact than the typical for-profit social enterprise), then perhaps we should be asking another question: How do we introduce better mechanisms to create rigor in high-performing non-profits, channel massive funding to them, and help them grow?

One such high-performing NGO is Educate Girls, which since 2007 has improved learning outcomes in 5,700 schools, enroll 50,000 girls in school, and reached half a million children in gender-gap districts in Rajasthan (where half of all adolescent girls are married before the age of 18, up to 95 percent of drop out of schools and over 50 percent face domestic violence). The organization does this through community ownership of government schools. In partnership with Instiglio, CRISIL, and a few other organizations, Educate Girls recently launched Payment by Results (PbR), a new initiative aimed at channeling larger amounts of funding to high-performing NGOs and helping them hold themselves accountable for their results. At the official launch of the initiative last week in Mumbai, Educate Girls and its partners explained the power of the PbR initiative for India and globally.

From left to right: Safeena Husain, Educate Girls; Michael Belinsky, Instiglio; Neera Nundy, Dasra; Raman Oberoi, CRISIL; and Gul Mukhey, Mentor Growth Capital.

Under Payment-By-Results, an NGO receives donor funding after it achieves a pre-described outcome. This has the potential to unlock larger amounts of donor funding and also allows the NGO more flexibility to take risks and be innovative, since funding is linked to outcomes instead of activities performed. To meet its working capital requirements to carry out the program, high net worth individuals or impact investors are looped into the mix; they supply the initial capital and when outcomes are achieved, donors pay back those investors, sometimes even with interest. To monitor outcomes, a third party employs rigorous evaluation methods, such as baseline studies and/or randomized control trials. Educate Girls hopes that implementing PbR in 200 schools will help it eventually scale to 30,000 schools, reaching 4.4 million children.

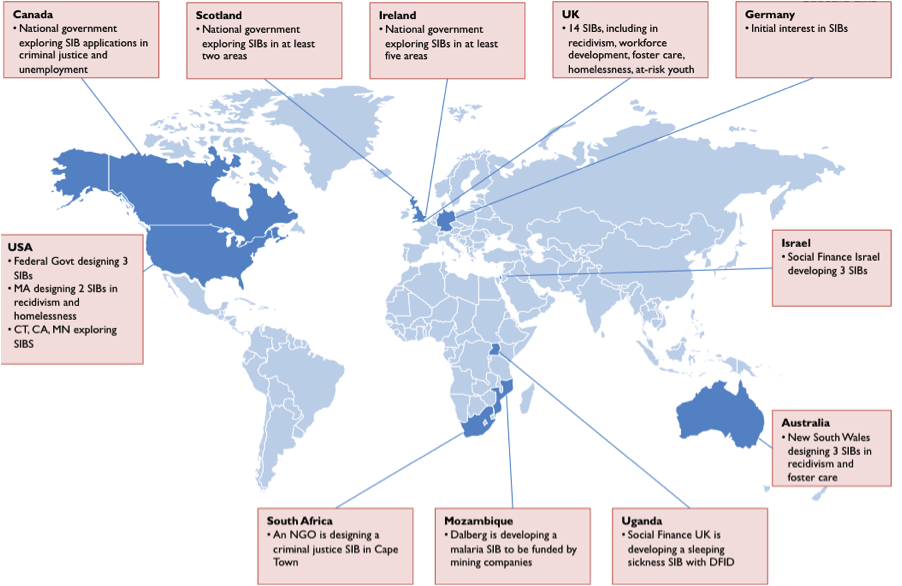

PbR is similar to social impact bonds and pay-for-success contracts delivered in other countries and sectors – the World Bank’s Results-Based Financing for Health projects are a good example, or the social impact bond pilot in Peterborough, England. (The graphic below shows similar projects sprouting up all over the world.) The difference here is that now we’re applying similar principles outside the public sector, actively involving private donors instead. Also, this is the first initiative of its kind in India, where the social sector is thirsty for more transparency and capital to scale quickly.

Source: Instiglio

Beyond its obvious benefits for NGOs, PbR gives impact investors the flexibility to contribute to and gain a better understanding of sectors outside their mandates that may not give large financial returns – including girls’ education and empowerment, which we know is one of highest-social return investments in existence toward a better world. (Besides the far-reaching benefits of lessened violence toward girls by allowing education to challenge dominant power structures, of women investing in and uplifting their communities, and of the proven benefit of educated girls having fewer children, the World Bank estimates that India could add $400 billion to its GDP as a result of increased participation of women in the formal economy.)

The way forward for impact investing is not clear, but we know impact investors have the capacity to be more creative about whom they fund and how – PbR is one example. And creativity is necessary, indeed, if impact investors are going to emerge from this bubble unscathed, and we are serious about channeling capital to the ones doing the toughest, system-changing work.

- Categories

- Impact Assessment

- Tags

- impact investing