The High Cost of ‘Data Darkness’ in the Developing World

Imagine two Indian women, Lakshmi, from Sulya, and Bharani, from Heggadadevankote. They live in the same general area in the same country. They speak the same language, wear the same kinds of clothes and share a common culture. They have similar personalities and capabilities, but they need very different things to succeed. Though they may live near to one another, the economy in which each woman operates is entirely different.

This would not come as a surprise if one of our would-be entrepreneurs hailed from the city and the other from a more rural countryside, but what if both women live in rural districts? What if they live only a few miles from one another? Surprisingly, their economies may still diverge enough to warrant separate inputs and business strategies.

Madura Microfinance is in the business of individual success with microloans. Our clients are largely poor women who live in rural districts in India. Our business strategy is intractably linked to the entrepreneurial success of our clients, which makes offering appropriate tools, trainings and products paramount to doing good business. Packaging and endorsing services that promote success is also essential to helping these women secure bright, secure and productive futures.

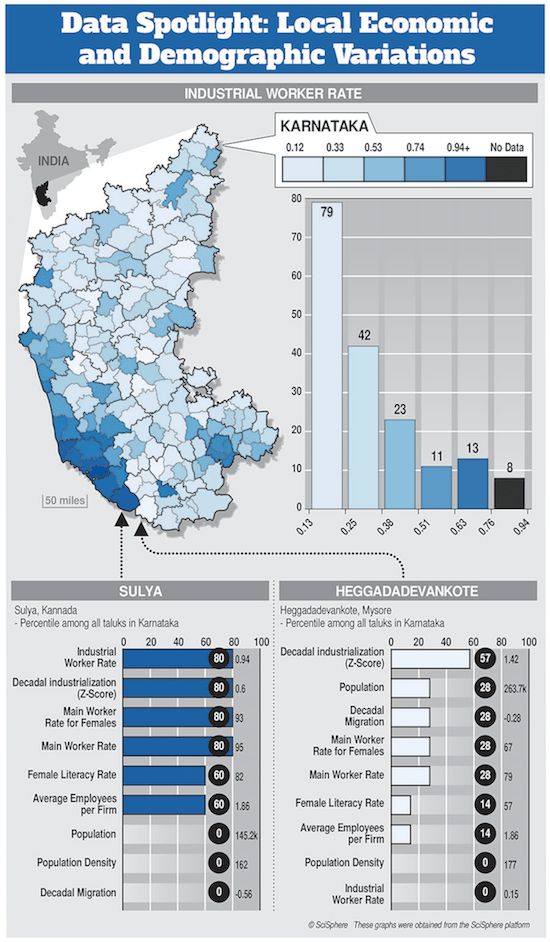

Simple matrices that treat Lakshmi the same way they treat Bharani are bound to fail. Despite being directly next to each other, these two taluks have distinctly different economies and demographics. Sulya is significantly more advanced. Industrial workers in this taluk earn in the 80th percentile for their whole district. Female literacy rates are at 82 percent. The main worker rate – the fraction of adult women employed more than half time – for women is 93 percent. Lakshmi has the opportunity to work in a factory, but she can also sell products to factory workers as they come in and out of shift.

Life in Heggadadevankote is different. The industrial worker rate – the fraction of the adult population employed outside of agriculture – is at rock bottom. The main worker rate for women is 67 percent, and only 57 percent of women can read. Bharani has no factory employment prospects. Her choices are to work as daily wage agricultural labor or sell products to the laborers. Her customers are likely to be less literate, less prosperous and without the regular salaries of factory work. To access products and markets, she has to travel further.

Life in Heggadadevankote is different. The industrial worker rate – the fraction of the adult population employed outside of agriculture – is at rock bottom. The main worker rate for women is 67 percent, and only 57 percent of women can read. Bharani has no factory employment prospects. Her choices are to work as daily wage agricultural labor or sell products to the laborers. Her customers are likely to be less literate, less prosperous and without the regular salaries of factory work. To access products and markets, she has to travel further.

This is not an anomaly. Take a close look at the map Madura Microfinance has created (left). It highlights several key economic statistics throughout the Karnataka district. Looking only at population would be misleading. It is important to recognize that dramatic differences beyond population can exist at the local level. There is no “average” level of industrialization and no shortcut to developing or prescribing appropriate development tools. With markets showing such different profiles, companies hoping to offer appropriate and economically beneficial financial products need to offer differentiated packages for these very different types of markets.

Today’s developed economies are digitalized. Information is widely available, waiting to be culled and analyzed. Social media, bank records, credit history and government tracking systems sliced and diced by ZIP code or neighborhood make it easy to design products and services for individuals and deliver them based on algorithms. Information is hyperlocal, personal and easily accessible. In comparison, the developing world is data dark. Gathering even the most elementary data is a monumental task. It requires feet on the ground, paid employees and auditing systems.

Based upon our research, however, the importance of this task cannot be overemphasized. Undifferentiated products and poor local knowledge result in inefficiencies on many levels. Products don’t have good market fit, customers don’t get what they really need, and the cost of customer acquisition and delivery is higher when you don’t know which customers to target for which product. This results in higher prices for lower-income customers. Without this data, products and services cannot be designed and targeted properly, leaving Lakshmi, Bharani and the businesses that serve them far behind the curve.

Tara Thiagarajan is the founder, chairman and managing director of Madura Microfinance.

Photos courtesy of Madura Finance.

- Categories

- Uncategorized