When People Say They ‘Lack the Money to be Banked’ – Here’s What They Mean

“I don’t have enough money.”

This response surfaces as the most common answer in surveys designed to uncover barriers to formal financial access. In the most recent World Bank Global Financial Inclusion Index (Findex) surveys around the world, the litmus test of financial inclusion, 59 percent of unbanked adults cited this as a reason for not being banked, surpassing all others. The response seems innocuous enough. But what happens when you dig a bit deeper?

Between 2014-2015, Bankable Frontier Associates worked with members of the Alliance for Financial Inclusion’s (AFI) Pacific Islands Regional Initiative (PIRI) and the UNDP Pacific Financial Inclusion Programme to collect baseline data on access to financial services in three member countries: Fiji, Samoa and the Solomon Islands. The synthesized results from those studies can be found here. In addition to collecting a set of PIRI indicators, which member countries had agreed to measure as part of a regional data measurement framework, these surveys also collected the Findex and G20 Basic Set of Financial Inclusion Indicators.

In these surveys, not having enough money also emerged, unsurprisingly, as the number one reason for not having a bank account among unbanked Pacific Islanders (80 percent of unbanked adults in Samoa, 56 percent in the Solomon Islands, and 50 percent in Fiji. It would be easy to dismiss this segment of the unbanked as unbankable. But doing so would mean ignoring the financial needs of more than half of all adults in these three countries combined. And doing so ignores a host of underlying reasons that might feed into this seemingly straightforward response.

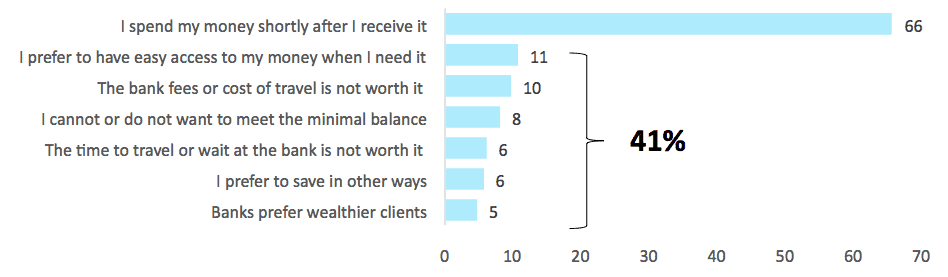

In anticipation of this, we asked unbanked Fijian adults to respond by explaining exactly what they meant by not having enough money in a recently completed national demand side survey. The findings illustrate that people do have money—but they hold onto these amounts for very short periods before they transact.

We know from the financial diaries that the poor live vibrant financial lives, using a multitude of creative strategies to stretch and grow their money and cope with volatility. But in addition to using formal and informal financial strategies, they also conduct thousands of small transactions on a regular basis. The responses from Fiji suggest that financial service providers may need to reconsider how they think about low-income, unbanked customers. Yes, savings are important—but so are flexible products that they can easily access to store and transact in their communities.

The remaining respondents in our survey pointed to other reasons for not having an account: the time required to travel to branches or other access points, the cost of travel or of keeping minimum balances, a perception that banks are for wealthy individuals only, or a preference for having money easily available when needed. For the poor, financial access must be understood in terms of the customer’s financial journey—once he or she has money to put aside, what are the other decisions or touch points that bring income to top of mind? And given these decision-points, how does the bank distinguish itself from the informal tools that are already available, familiar, proximate, and/or easy to use?

As those in the financial inclusion industry have argued for some time now, access is not enough. By the Numbers, a recent report by the Center for Financial Inclusion, points to the fact that in low- and middle-income countries, usage of bank accounts has not increased even though access has. While people in these countries, including low-income individuals, save and borrow extensively from informal sources, such as friends or family, local shops, moneylenders or savings groups, institutions do not yet fit into this picture. This was also true in Fiji, Samoa and the Solomon Islands, where 71 percent, 61 percent, and 87 percent of adults, respectively, had saved money in the past year, though largely in places that could be accessed quickly, such as at home. Thus, while governments make efforts to drive bank account openings, many will likely continue to be disappointed by low usage, as has happened with India’s most recent financial inclusion drive, Jan Dhan Yojana.

RELATED ARTICLE: WHAT STANDS BETWEEN WOMEN AND FULL FINANCIAL INCLUSION?

Financial service providers and policymakers should embrace opportunities to break down barriers to formal account usage during the product design process, and continually test and iterate before products go live. Above all, they must ask the hard question of whether the products truly compete with entrenched solutions and offer the value-proposition that low-income clients seek.

While providers and policymakers have expanded their financial inclusion offerings to include savings, credit and insurance, payments and appropriate transaction accounts should not be considered inferior or of lesser importance. Instead, for the 59 percent of unbanked individuals who “don’t have money” for a bank account, safe, accessible and flexible transaction products may be exactly the right first step into the formal financial world.

Photo credit: Stephen Rees, via Flickr.

- Categories

- Uncategorized