An Ironic Impact of COVID-19: Will the Pandemic Put Digital Health (Finally) on the Path to Reducing Health Inequalities at Scale in Emerging Markets?

COVID-19 and its associated lockdowns have worsened access to healthcare and widened health inequalities around the world. At the same time, the crisis has offered a solution to the problems it has caused by opening the door to healthcare via telemedicine or other digital services. Since the outbreak started, digital health services — such as doctor consultations through online chat or over the phone — have experienced tremendous growth in both developed and developing countries. Now, as a vaccine promises to bring a gradual end to the pandemic, the big question remains: Can the digital health services that have become the new normal in the past year help to close inequalities in access to healthcare over the longer term?

AXA Emerging Customers is the financial inclusion arm of AXA, working in 12 emerging markets to protect low- to middle-income people with simple and affordable insurance. In 2020, we bundled digital health services with 15 of our inclusive insurance schemes across nine countries, reaching 1.8 million people. We did this for both social and economic reasons: Digital health has a big potential to improve health outcomes for lower-income people. It also makes our insurance proposition more tangible, and hence should increase sales and renewals. In addition, if these services help people develop healthy behaviors, our hospital claims should go down. With these cost savings, and since the actual cost of digital health coverage is not a huge percentage of the premium collected, we often were able to add it without increasing the price of insurance to customers.

Most of these schemes are administered by third-party telemedicine providers, which are paid by AXA for their services just like any other healthcare provider. But there is one key difference between these projects and more traditional digital health coverage that is just added to health insurance policies for affluent customers: All of these inclusive insurance schemes are delivered through business-to-business-to-customer distribution partnerships. That means AXA does not offer insurance services to low-income people directly, but rather through a partner-agent model. So microfinance institutions and other partnering businesses and organizations are our distributors, and we insure their customers. Last-mile distribution by trusted agents of our partners is a key element of scaling up both inclusive insurance and digital health massively.

The early success of these projects suggests that digital health initiatives can continue their momentum after COVID-19 ends. But to make sure they work for lower-income people, they need to be deployed on a mass scale, with the right engagement tools to facilitate adoption and ensure consistent utilization in the long term. Unless these efforts are prioritized, consumer behaviors won’t change, and healthcare access and quality will remain fragmented and inconsistent in these markets, with no clear way for patients to obtain the right care at the right moment. Below, we’ll discuss how digital health initiatives can build upon the progress they’ve made during the pandemic.

How Digital Healthcare Can Address Growing Health Inequalities

COVID-19 has increased existing health inequalities within countries and regions, with higher infection and death rates among people from poorer backgrounds who live and work in crowded conditions. Not much data is available for emerging markets, but the data from Europe clearly illustrates this health equality divide. Between the start of March and the middle of April 2020, age‐adjusted death rates in the poorest areas of the U.K. were more than double those in the wealthiest areas.

This discrepancy might get even worse, for three main reasons. First, low- to middle-income people are more prone to develop a chronic disease, which often remains undiagnosed — and which can increase the severity of COVID-19 infections. In France, the odds of developing severe COVID-19 are seven times higher in obese patients, three times higher in diabetics, and 3.5 times higher in patients with hypertension. Second, lower-income people are often fearful of visiting healthcare facilities, which may lead to delayed treatment of COVID-19 and other serious illnesses. Third, the further you go down the income ladder, the more taboo mental health disorders are — and the more professional support is limited. As a result, pandemic-induced anxiety and depression are ravaging low- to middle-income people — a population that’s already more likely to be laid-off and to live in precarious conditions, which can further exacerbate mental health issues.

The gap in access to healthcare is more acute in emerging markets, where the majority of the population has unequal access to health services. The WHO estimates that about 150 million people around the world suffer financial catastrophe from out-of-pocket health expenses each year, while 100 million people are pushed below the poverty line. Low- to middle-income consumers often forego treatment, as they can’t afford it, can’t navigate the health system, are not diagnosed for chronic conditions, and rely on informal medical advice. That means they often end up in hospitals when their condition becomes too serious to manage, leading to costly and often tragic results.

The story of Lydiah, captured in the recent book by Julie Zollmann, “Living on Little,” memorably illustrates this problem. At age 27, Lydiah, a young woman in Kenya, was experiencing a lingering illness. She went to the hospital at least four times during that year, and each time she was told she had malaria. On each visit, she would be given a new medicine. After showing no improvement, she started going to private clinics — but that didn’t help either. As a last resort, she turned to traditional medicine, but her condition continued to worsen. Then, just before Lydiah died, she was diagnosed with very late-stage tuberculosis. By that point, her family had spent a fortune on various treatments, yet tuberculosis care is free in Kenya. As Zollmann rightly explains, “Low-income people are subject to a substantial quality tax, with treatment costs escalating as individuals seek care from multiple providers to resolve even common illnesses.”

Imagine if Lydiah had access to standardized health advice via telemedicine. That was the case for Elham, a microfinance borrower living in Minya, who runs a small shop and takes care of her family of four. She is one of the half a million-plus borrowers AXA Egypt insures through partnerships with microfinance institutions, as part of our AXA Emerging Customers program. Elham got access to telemedicine provided by Altibbi, a healthcare company with whom we partnered during the first lockdown to increase access to digital healthcare. Her son had a severe fever just after the Eid holiday last May. She thought he’d gotten COVID-19, but she was too scared to take him to a healthcare facility because of the virus. So she used Altibbi’s digital health services, which referred her to a safe place to do lab tests. It turned out that her son did not have COVID-19, and after multiple tele-consultations, her doctors found the right treatment. “If I didn’t have access to Altibbi, I wouldn’t be able to access healthcare at this time,” she said. And in fact, obtaining healthcare had not been much easier for her family even during “normal” times. Elham often went to clinics where she needed to wait a couple of hours for service, losing her income for half a day. Since these clinics were costly, she would rarely see a doctor for herself or schedule any follow-up sessions for her children. Digital healthcare can provide a valuable alternative for families like hers.

Creating a Successful Digital Health Model

Discussion of the promise of digital health is nothing new in global health or development circles. It has long been recognized that there are major benefits to offering high-quality standardized advice through digital services. This approach allows providers to detect issues earlier, keep patients out of the hospital unless necessary, and engage them on daily health maintenance issues to raise their awareness and improve their lifestyle.

The concept has been proven to work in a low-income context by Telenor Health in Bangladesh: It created Tonic, one of the first successful digital health deployments in emerging markets, which was recently acquired by Grameen Bank. Using both freemium and paid-for models, it offers several packages that include a limited call-a-doctor service, health tips, a discounts network, and the option to book appointments with relevant specialists. The company has served more than eight million people over the last two years.

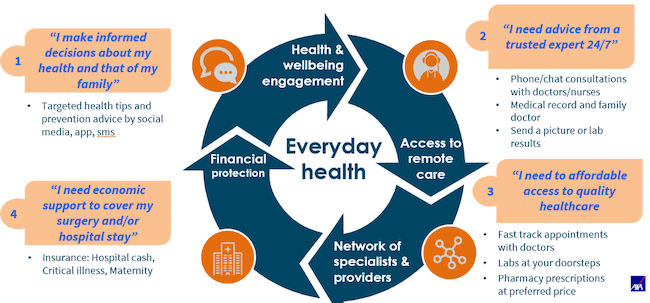

The way we think about digital health at AXA is inspired by the Tonic example. Digital health is not just about offering a medical hotline; it is about creating a comprehensive health ecosystem to improve access to quality, standardized care. As shown in the diagram below, the first component of a successful digital health model is to become a trusted advisor on health and to offer nudges that can change patient lifestyles for the better. The second is to provide access to medical advice over the phone and to create a medical record that can be used to better advise patients in the future. Continuity is key, as well as maintaining high quality through detailed, standardized clinical pathways and appropriate clinical governance. The third component is to provide access to offline services at a discounted price, especially to labs and specialists. And the fourth is to offer financial protection in case of catastrophic health expenses. The first three components make the value proposition tangible to patients in the short term, while insurance cements the proposition and makes it relevant in the long term.

AXA Emerging Customers’ digital health response to COVID-19 and beyond

COVID-19 has accelerated AXA Emerging Customers‘ digital health agenda. From just two live projects that bundle digital health and inclusive insurance at the beginning of the year, we ended 2020 with 15 schemes serving low- to middle-income consumers. Among these projects, the typical solution includes targeted health content campaigns and covers access to teleconsultations with certified doctors. We often bundle this with simple and affordable life, accident, and health insurance products.

While these solutions might look similar, our actual Emerging Customers portfolio is diverse in terms of target groups, business models, and distribution partners, which creates a unique opportunity to test and learn. We are serving migrant workers in Malaysia and the United Arab Emirates, e-hailing service drivers in Mexico, bank account holders in Indonesia, mobile wallet users in the Philippines, and factory workers in India.

We started many of those projects in response to COVID-19, providing digital health insurance for free to the customers of our existing distribution partners — including the MFIs in Egypt mentioned above, a mobile wallet company in Mexico, and a telco in Thailand. Many of these services evolved into paid-for offerings with bundled insurance, as was the case for digital health provider Alodokter in Indonesia and a large retailer we partnered with in Brazil.

Digital health can only work if it focuses on customer engagement

The key lesson we’ve learned from our digital health schemes is that continuous engagement is essential to making sure people discover the service and keep using it in a consistent way. If people use the service once or turn to it only for emergencies, digital health will not fulfill its potential to reduce health inequalities. Instead, these services need to become a trusted navigator that helps people to change their lifestyles and seek care at the right moment and in the right places. Our main competition is a corner shop that sells common medicines, which customers turn to in the absence of more formal care. The behavior change challenge is huge.

To that end, utilization is a key metric: For digital health to become the top-of-mind health navigator for the masses, it needs to be used by each family at least once per year (i.e., a 20-25% unique utilization rate for all members over a year). This can be achieved with 2-5% unique utilization every month. Before COVID-19, the average utilization rates across the industry for traditional digital health schemes were much less than 1% per year. In contrast, some of our most successful pilots have achieved 10-15% utilization per month. There are several factors that can make this sort of uptake possible:

- Ongoing engagement is key to driving utilization. For instance, Altibbi, our telemedicine partner in Egypt, sent SMS text reminders that increased service usage by five times compared to a control group with no reminders. They also did reminder calls for those not using the service, leading 84% of recipients of these calls to use it.

- Not all telemedicine providers have the capability to drive utilization for mass consumers; mass schemes require multi-channel marketing, creative user engagement, and performance-based agreements.

- A customer journey that requires downloading an app results in very high drop-off (75-95%) during the enrollment process; instead, social media messenger bots are key.

The COVID-19-driven digital health revolution is just beginning. The jury is still out, but ironically the pandemic may actually accelerate the closing of the healthcare access gap in emerging markets. Adoption remains a challenge, and emerging customers are different from affluent ones — hence, different engagement approaches are required to get them to discover digital health services and sustain their usage. Other building blocks, such as technology and mass-scale distribution, are already in place. Today’s technology allows stakeholders to create a health ecosystem that is efficient even in low-cost environments. Our distribution partnerships promise to bring this healthcare option to millions of customers in emerging markets, offering trusted, standardized clinical advice that wasn’t previously available at scale.

Michal Matul is head of digital health and Niti Pall is senior advisor on digital health at AXA Emerging Customers.

Photo courtesy of Anna Shvets.

- Categories

- Coronavirus, Health Care, Technology