Reaching Informal Savings Groups with Formal Financial Products: A Study’s Unexpected Findings Reveal the Challenges of Digitizing Transactions

Formalizing the financial activities of savings groups and other informal savings mechanisms (ISMs) has long been a priority in the financial inclusion world. Savings at the Frontier (SatF) began with precisely this goal in mind. A six-and-a-half-year programme (2015-2022), SatF seeks to bridge the gap between the supply of formal financial services and ISMs, so that ISM users have greater choice and can access the financial services that best meet their needs.

As the programme nears completion, SatF is supporting the efforts of 10 financial service providers (FSPs) in Ghana, Tanzania and Zambia to test and deepen their commercial relationships with ISMs. Previously, in 2019-2020, we carried out the first round of an evaluation using the Qualitative Impact Assessment Protocol (QuIP) in these three SatF-supported countries. Through qualitative interviews and focus discussions, the evaluation tested SatF’s theory of change, which assumed that ISM users (i.e., savings group members) would be linked to FSPs through the creation of group accounts at these financial institutions to hold group savings.

SatF had assumed that when FSPs formalized these group savings, it would lead ISM users to open individual accounts with these providers, to facilitate digital group-to-member (G2M) and member-to-group (M2G) transactions. By digitizing these transactions, we expected that savings groups and their members would be able to lower transaction costs (e.g., by reducing the time needed to collect and disburse payments to and from the group) while also storing their money securely and earning interest on the balance.

But the results of this evaluation challenged these assumptions – and SatF’s theory of change. I’ll explore these findings, and their implications for efforts to digitize savings groups, in the article below.

Why are Digital Interactions Among Savings Groups So Low?

The findings from the Qualitative Impact Assessment Protocol synthesis confirm that ISM users do open individual accounts. However, they do not typically use these accounts to contribute to or receive loan disbursements from group savings. The monitoring data that SatF’s partner FSPs gathered as part of regular program assessment supports this finding: Despite relatively high uptake and usage of both group and individual bank accounts, digital M2G/G2M transactions remain low.

Why are member-to-group and group-to-member (digital) interactions so low?

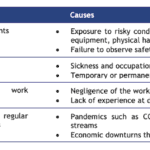

In discussion with our partnering FSPs, SatF has identified five potential reasons for low uptake of M2G/G2M digital channels.

First, for a few ISM users, saving in different accounts (group vs. individual) helped them organize the money in different “buckets” for different purposes. Savings with the group accounts tended to focus on long-term goals (e.g., business investments), while individual accounts were more likely to be used to save for short-term or unexpected needs. This distinction calls into question the utility of linking group and individual accounts digitally, because the two represent different tools in ISM users’ mental accounting.

Second, in contrast to the first reason, some users saw the accounts as serving essentially the same purpose, with little need to have both. One group said their members didn’t have enough money to save in personal accounts on top of their group contributions. The positive peer pressure of savings groups and the requirement to contribute to retain active member status might also lead savers to prioritize saving in the group. This suggests that individual accounts serve as a “container” for any leftover money after savings to the group are made.

Third, digital or mobile G2M/M2G transactions raise the problem of double bookkeeping for ISMs, requiring them to reconcile digital transactions and balances with cash balances. Understandably, ISMs are reluctant to take on this additional work, especially since one of the key value offers of ISMs to their members lies in the transparency of transactions: Group members can see the cash, both when they contribute and when they take out loans. They can also physically check the lock box at meetings. So far, none of SatF’s FSP partners have found a digital solution to streamline and integrate this process while maintaining this degree of transparency and convenience.

Fourth, one key value of formal ISM accounts to users is that they provide interest payments, and potential future access to loans from the FSP that provides the group account. However, FSPs’ low interest rates were often cited as a deterrent to opening and using both individual and savings group accounts. This is corroborated by a 2019 SatF study on ISMs and their users in Zambia, which found that in order to be attractive, FSP value propositions had to “put users’ money to work” to earn more money, instead of just allowing it to sit idly.

Fifth, in two cases, ISM users saw individual bank accounts and mobile money accounts as interchangeable, with mobile money sometimes preferred because the agents are already known to users, and because it can be used for a variety of payments/transactions outside the group. This points, once again, to the importance of understanding user needs: Those who want to balance security with liquidity may prefer mobile money, whereas those looking for mechanisms that enforce restraint and commitment might prefer bank accounts, which are harder to access and therefore offer a greater degree of protection from impulse spending.

Further Questions for Digitizing Informal Savings Group Transactions

These findings on digitizing G2M/M2G transactions raise several questions that FSPs and financial inclusion programmes may find useful to consider:

- Are formal individual accounts more of a “substitute product” to group savings (formal and informal), rather than a complementary product?

- Is the value proposition of individual bank accounts in relation to mobile money accounts (in terms of interest, fees, transaction charges and platform compatibility) clear to clients? Or are they both seen as rather similar containers for individual savings that can be easily accessed?

- Instead of the current focus on linking formal individual accounts with formal group accounts by digitizing transactions between them, could a more useful conception of linkage center on FSPs engaging purposefully and strategically with ISMs and capitalising on their peer networks and peer learning mechanisms to establish ongoing visibility into ISM members’ priorities? In other words, can we stop thinking only of linkages as products and services, and start thinking of them as the relationships that enable FSPs to meaningfully serve these clients?

- For FSPs, it will become important to understand and serve collectives or communities rather than individuals—not just when developing products for a group, but also products and services aimed at individuals. This is because technology diffusion in rural communities is significantly shaped by peer-to-peer learning and exchanges. FSPs might want to learn more about group and community dynamics if they aim to serve rural ISMs or smallholder farming communities. Many do this already by identifying lead farmers or community leads. What other strategies might help to make this shift in FSPs’ “unit of analysis” from individuals to communities?

Clearly, more research to understand client behavior and needs is required to answer these questions. SatF is currently completing our second round of data collection using the Qualitative Impact Assessment Protocol methodology, and we hope the findings may help answer some of these questions, while providing further insight into how FSPs can better develop financial products that suit the needs of clients in emerging markets.

Raksha Vasudevan is a monitoring and evaluation specialist and a consultant with the Savings Learning Lab, which is a learning partner of the Savings at the Frontier program.

Photo credit: Riaz Jahanpour for USAID / Digital Development Communications.

- Categories

- Finance, Impact Assessment, Technology