Four Reasons Kenya’s Economy Might Not Be as Inclusive as You Think

Kenya seems like nirvana when it comes to building inclusive economic systems. After all, the country has attained 82% financial inclusion and an astounding 73% of Kenyan adults have a mobile money account. Entrepreneurs across sectors have taken advantage of this access to re-imagine service delivery, allowing them to reach previously unreachable customers. From energy to healthcare to agriculture to education, Kenya’s change-makers are disrupting the status quo.

But a closer look reveals that the “Silicon Savannah” might not be as inclusive as it appears.

Recently, as part of the launch of my new book, “Access for All: Building inclusive Economic Systems,” DAI brought together Kenya-focused businesses and organizations to discuss a simple question: How inclusive is the Kenyan economy? Here are my takeaways from the discussion.

1. Digital access ≠ economic inclusion

Tech innovation in Kenya has certainly enabled entrepreneurs to tackle the three key obstacles to reaching low-income people with much-needed services: availability, affordability and quality.

Take M-Kopa, a Nairobi-based social enterprise that delivers solar home systems using a “pay as you go” model. Customers buy the systems and pay them off at around 50 cents a day — roughly what they might spend for kerosene to light their homes, or fees for charging their phones. As long as they pay via M-Pesa, their solar electricity stays on, as they pay off their unit over time. The impact of this access to solar energy is dramatic: M-Kopa’s 700,000 client households will save $450 million over the next four years and enjoy 75 million hours of fume-free lighting per month.

But despite these promising numbers, M-Kopa has found it difficult at times to reach the very bottom of the pyramid. The down payment – starting at $18 – and the daily payments may still stretch the financial capacity of those making $2 per day, M-Kopa’s core demographic. (M-Kopa needs to charge a deposit because Kenya’s underbanked population does not yet have adequate credit scoring, and though impressive strides on credit scoring in Kenya have been made in recent years, it is still in its infancy.)

Tala presents a different kind of challenge. The company is among the new generation of mobile lenders offering Kenyans short-term loans almost immediately, by sidestepping the traditional credit-scoring system. Using unconventional behavioral data, such as a customer’s history of paying bills on time or having a wide social network, Tala’s artificial intelligence predicts their creditworthiness. This approach opens access to bank loans for customers who have a smart phone but lack sufficient collateral.

But while this is a valuable service, some analysts have raised concerns about the high price of these loans. CGAP estimates Tala’s annual effective interest rate to be 61% – 243% – numbers that are fairly typical of Kenya’s digital credit providers. It’s easy to see how rates at this level could place a burden on low-income borrowers, potentially counteracting the value they get from digital inclusion.

2. The enabling ecosystem is not fully functional

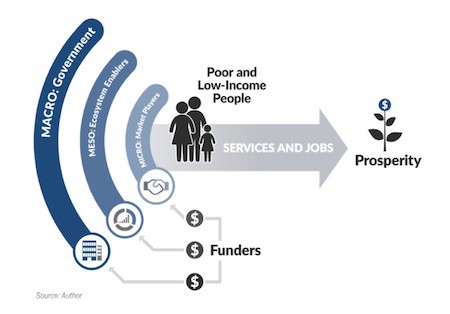

To hunt for signs of inclusion (or exclusion), we need to look beyond the “micro level” where M-Kopa and Tala operate. For instance, “Access for All” looks at the “meso level,” which includes “ecosystem enablers” that connect supply and demand. In Kenya, three primary issues are complicating these enablers’ work:

-

-

- Credit bureaus: Information about a customer’s own financial and transaction track record is critical for access to credit. But Kenya’s credit bureau only records data from the banking sector, omitting transactions and credit history across other domains, including mobile credit. Until more information is accessible, many potential borrowers will be locked out of formal services.

- Interoperability: In Kenya’s telecom market, Safaricom remains dominant and it’s cumbersome to transfer money across platforms. When operators make it easier for customers to transact across platforms, this will likely improve value for customers and extend access. This is a priority for FSD Kenya, a financial inclusion program – and for other stakeholders in the sector.

- Incubators and Accelerators: Nairobi’s proliferation of incubators and accelerators—and thus startups—is impressive and encouraging. But can Kenyan and international markets sustain all this unbridled innovation, much of it aimed at reaching the currently excluded? The GSMA reports that Kenya has 30 tech-related hubs, which doesn’t include other less technology-driven efforts. Meanwhile EMPEA, the global industry association for private capital in emerging markets, registered only 32 venture capital deals in all of Africa in 2017. If each accelerator produces multiple start-ups, where can they get funding?

-

3. Government policy: plusses and minuses

Government policy can improve inclusivity. In the early days of M-Pesa, for example, Kenya’s government adopted a flexible policy allowing Safaricom to experiment and grow its novel business model. Today, the country’s Central Bank is promoting “sandboxes” — safe spaces for financial technology companies to try innovations without running afoul of the law.

However, the recent government-imposed interest rate cap of 13% for banks has virtually halted lending to low-end clients, because it’s no longer viable for banks and microfinance institutions to do so. With no other options, customers are forced to pay the super-high rates charged by mobile lenders and others. While lawmakers are rethinking the policy (the Nairobi High Court recently ruled the cap unconstitutional), it remains to be seen whether access will trump the political imperative to keep rates low.

4. Pay more attention to Kenyan capital

Where does all the money come from to fuel the innovation at Kenya’s micro, meso and macro levels? Capital of all varieties is flooding into Kenya from outside, chasing investment opportunities both in the country and the region. The donor community remains active, contributing nearly $2.5 billion in overseas development assistance in 2017.

Recognizing that this money alone cannot solve Kenya’s problems, donors are increasingly using their limited funds to crowd in private capital. USAID’s East Africa Trade and Investment Hub, for example, mobilized $170 million into priority sectors such as agriculture, energy and manufacturing. The Hub leveraged a partnership with CrossBoundary to help mobilize most of those funds. Although this is small potatoes compared to the $2-3 billion in private funds streaming into Kenya, donor-mobilized investments are likely to yield more inclusive outcomes than pure commercial plays.

Some are also concerned that the focus on external investment risks crowding out domestic capital markets. It’s worth remembering that the amounts of money locked up in Kenya’s banking sector and with institutional investors, such as pension funds and insurance companies, dwarf any foreign direct investment that Kenya attracts. So, how can domestic capital be unlocked to promote inclusive economic growth?

Kenya’s important moment

This is by no means a comprehensive list of the challenges and opportunities for inclusive growth in Kenya, and other issues exist. For instance, while access to new services offers a pathway out of poverty, access to decent jobs is also critical. Most Kenyans work at informal jobs. Many of these jobs are unstable, precarious and even dangerous. Formal employment has represented only around 17-18% of employment in Kenya every year since at least 2010. Ecosystem enablers are creating new ways to connect Kenyan job seekers to employers in the informal sector, but that still leaves workers in a “grey zone” between the formal and informal worlds.

However, the country is uniquely positioned to overcome these obstacles. As I highlight in “Access for All,” Kenya has long been a leader in economic inclusion, and its challenges offer a preview of what we can expect as other countries follow it. That’s why it’s essential to find ways for Kenya to move forward at this important moment, as true economic inclusion and growth for a majority of its citizens gradually come into view. To ensure greater access for all, diverse ecosystem actors will need to pull together for the next round of innovation and improvements. Given the Kenyan spirit of harambe (Swahili for “all pull together”), anything is possible.

Brigit Helms is the Vice President of Technical Services at DAI.

Photo courtesy of Ninara.

- Categories

- Finance, Technology