Under-Leveraged Best Practices for Scaling Productive Use of Energy Appliances: Part 2 — Financing Options

Productive Use of Energy (PUE) appliances are energy-using and income-generating devices that include everything from solar mills and walk-in cold rooms to solar water pumps and refrigerators. They are the subject of growing attention in the development sector due to their multiple impacts, as they can increase revenue for low-income populations and mitigate the effects of climate change, while also improving global energy access by driving greater electricity consumption per user, enabling energy businesses to expand into new communities.

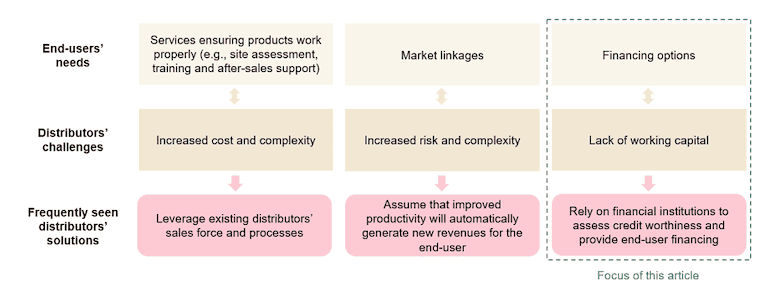

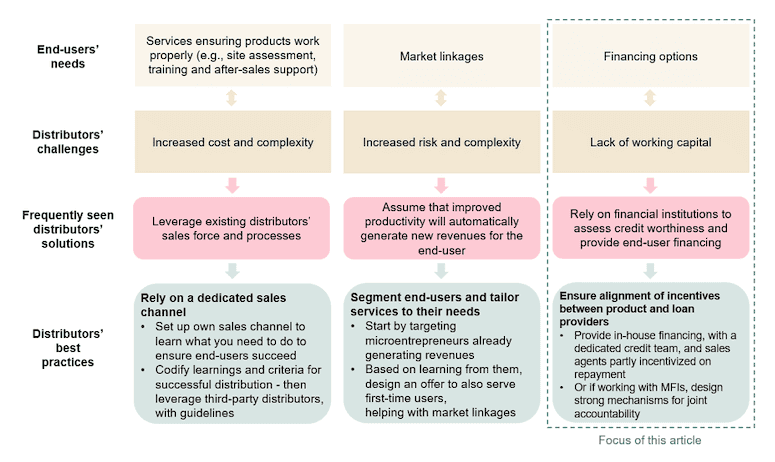

However, PUE appliance manufacturers and distributors are facing a number of challenges, and in attempting to address them, they face some persistent myths that are resulting in suboptimal choices.

In a recent NextBillion article, we discussed two of those challenges, involving sales support and market access. In the article below, we’ll explore a third challenge: how to handle the high level of working capital and financial skills required to offer financing options to end-users. As in the previous article, we’ll discuss this challenge as it relates to the two PUE appliances with the most mature and promising markets, solar water pumps (SWPs) and solar refrigerators.

The Affordability Challenge for PUE Appliances

Affordability is a key barrier for end-users, as PUE appliances are significantly more expensive than their traditional alternatives. The cheapest SWP we’re aware of is currently retailed at US $420 (KSH 54,999) in Kenya, while petrol pumps can be found for less than US $150. Whereas the petrol pump has a much higher flow rate, the long-term savings on fuel makes SWPs less costly over 10 years, for an equivalent irrigated surface.

However, end-users are highly price-sensitive: A recent market study performed by SunCulture in Kenya has shown that a 28% price decrease on one of its solar irrigation products — covering both upfront and monthly payments — led to a 330% increase in sales. There are many ways PUE distributors could lower retail prices, including by leveraging results-based financing, selling carbon credits, redeploying used products at a discounted price or lowering manufacturing costs. Yet most clients are likely to still require end-user financing.

To meet that need, distributors face a high temptation to rely on external actors — such as specialized banks or microfinance institutions (MFIs) — to act as loan providers, and sometimes also as final distributors. Performing credit risk assessments and handling payment defaults are complex activities, which — in the absence of such partnerships — would require distributors to develop new expertise. And providing this financing themselves requires high amounts of working capital, which can put distributors at risk or significantly slow down their growth.

The Challenges of Partnering with MFIs

However, in practice, very few — if any — partnerships between PUE distributors and MFIs have worked well so far. This is broadly true for the sales of any complex durable product, as previously documented in a Hystra report on companies selling beneficial product categories, which found that at best one in 10 such partnerships thrives over the long term. Reasons for this low rate of success include:

- Misaligned incentives: When distributors are not in charge of end-user financing, they have fewer incentives to ensure that end-users succeed in leveraging the appliance to generate enough revenue to repay their loans. As a result, they do not necessarily provide all the support and services that end-users require, even though it would be in their long-term business interest to maximize client satisfaction and word-of-mouth. These misaligned incentives also explain why various projects subsidizing PUE appliances — in particular SWPs — have seen low long-term adoption rates. In West Africa, we spoke with the distributors involved in one such subsidy scheme, who understandably looked to maximize the number of pumps sold during the subsidy period, and sometimes neglected the field and business case assessment for end-users. As a result, a number of pumps ended up in fields where they simply could not work due to ill-adapted water access. This created a lot of dissatisfaction among farmers and started to discredit the overall SWP industry locally.

- Creditworthiness assessment intrinsically linked with the PUE business case (and hence requiring technical skills that few MFIs would have): The first step in assessing whether a PUE client will be able to repay a loan is understanding the extra net revenues this client can expect to earn thanks to the new appliance. This requires specialized technical — and sometimes agri-business — skills that MFIs rarely have. As a result, some MFIs end up being too strict in their assessments, refusing to grant loans to a substantial proportion of clients pre-selected by PUE distributors, and creating dissatisfaction both at the farmer and distributor level. This is particularly true for smallholder farmers, who are perceived as risky clients by MFIs, which can strongly limit the uptake of SWPs sold on credit. Conversely, other MFIs have not been strict enough in their risk assessments, leading them to grant loans that clients could not repay, and resulting in high default rates. When this happens, distributors are still obliged (in practice) to handle default situations, as failure to do so would lead the MFIs to stop giving loans to future customers. Hence, the distributor spends its time chasing money without being paid the corresponding interest rates which make this time investment acceptable to an MFI, thereby creating a strain on the MFI-distributor relationship. For instance, a solar refrigerator company we spoke with relied on a large MFI in sub-Saharan Africa to distribute its products to the MFI’s clients using end-user financing. The company rapidly ended this partnership after experiencing many client complaints and high default rates.

- Bureaucracy and a lengthy credit approval process compared to rapid sales processes: Several PUE distributors we spoke with also reported that cumbersome administrative procedures discouraged prospective customers from borrowing from MFIs.

Solutions to Provide End-User Finance to Customers and Working Capital to PUE Distributors

In response to the challenges discussed above, some PUE distributors have set up tripartite contracts between themselves, the MFI and the end-user. This type of arrangement can potentially work if the PUE distributor has a direct incentive for its clients to repay, and a joint (and efficient) creditworthiness assessment takes place. Bonergie is currently testing this model in Senegal, having signed a partnership with two MFIs to sell 500 SWPs. The company is first performing a site/credit assessment of the farmer, before the MFI starts its own credit scoring process. If the MFI agrees to offer credit, Bonergie receives 80% of the pump’s sale price upon installation, with the remaining 20% being paid over the subsequent 18 months — a timeline that also incentivizes effective after-sales service. In case of default, the MFI can ask Bonergie to repossess the SWP, which will be sold second-hand to cover the remaining balance owed to the MFI. If successful, this model could become a blueprint for new forms of partnerships that can alleviate distributors’ cash flow constraints and support SWP scale.

Another model, which has already proven to work, is to ensure that one entity remains accountable for both the end-user’s success and repayment, as both are tightly linked. So far, this model has only achieved success when the PUE distributor provides the financing and takes on the credit officer role, charging interests accordingly. Although challenging, this has proven to be less of a stretch than asking MFIs to take up the complex sales, distribution and after-sales process required to sell PUE appliances. SunCulture is one distributor that is taking this integrated approach, providing in-house financing through a dedicated credit assessment team, independent from the sales team. The company systematically checks end-user data on a public credit risk database, and administers a customer data survey to validate creditworthiness. The credit officer has the final say on the sale, not the sales agent — a best practice commonly recommended in the broader PayGo sector. Additionally, SunCulture only pays sales agents 50% of their commission on credit sales upfront, with the remainder paid two months later — as long as their customers made their first payments on time. This practice aligns sales agents’ incentives not just to sales, but to quality sales. As a result, the company has high repayment rates (>90%) for the 85% of its SWPs sold through PayGo, and high end-user satisfaction rates (a Net Promoter Score of 59 in an industry with an average of 26). SunCulture financed the working capital requirements that have enabled this approach through a $12 million syndicated debt facility between several funders.

But not every PUE appliance distributor has access to that sort of funding. In order to help existing (mostly small) PUE distributors raise the necessary working capital to provide credit, there is an opportunity for development finance institutions to provide dedicated concessional credit lines. PUE distributors would ideally benefit from more attractive terms than individual customers, and they could use the interest rate difference to fund their own lending operations. This is how IDCOL, a state-owned development finance institution dedicated to promoting and financing infrastructure and renewable energy projects in Bangladesh, funded the growth of the national solar industry. They provided concessional lines of credit to solar home system distributors, which then sold these products on credit to their clients. Several of these distributors have sold over a million units.

Off-balance-sheet securitisation could be another way to alleviate this working capital constraint, by having a third-party partner buy the company’s PayGo receivables, similarly to what Sun King or d.light did for their PayGo solar home system sales. However, this approach is currently only used by larger firms with long track records, and it would need to be adapted to PUE companies, most of which are still small.

Finally, given the expected socioeconomic impact of SWPs and solar refrigerators, pay-for-impact models or public subsidies could be justified — e.g., the World Bank UgIFT program in Uganda. These can help limit distributors’ working capital needs — and the final amounts paid by end-users — while supporting long-term uptake, as long as the support incentivizes companies to maximise not PUE sales volumes, but rather the number of appliances still in use over time. This will ensure that companies provide everything their users need to fully reap the benefits from their PUE appliance.

While this two-article series has tried to debunk three persisting myths in the PUE appliance sector, it is not intended to be an exhaustive assessment of what is needed for PUE companies to scale. We hope that it can still provide some pointers on what it takes to build successful PUE appliance distribution models, as these can hold immense potential across different value chains.

It’s important to recognise that PUE distribution companies — which stand at the nexus of energy, agriculture and tech — are still not receiving the attention they deserve. Given their potential for impact and the complexity of the challenges they’re tackling, they urgently need additional support. And this support must go beyond just traditional financing to also include grants to enable more experimentation on the business model side, as well as technical assistance to avoid reinventing the wheel. This will help ensure that these companies are equipped to overcome the challenges of serving their customers well, instead of being forced by short-term economics to choose sub-optimal, cheaper solutions which can be detrimental to the long-term health and growth of the sector overall.

This article is the second of a two-part series written by Hystra in collaboration with the Global Distributors Collective and with the support of British International Investment‘s technical assistance facility, BII Plus. Read the first article here.

Part of this article is based on our research with our partner ISF Advisors, on the current state and future potential of small-scale irrigation: Access the full report here. This report was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The opinions and findings expressed within are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views, strategy or funding priorities of the Foundation.

Thomas Charoy is a consultant at Hystra; Lucie Klarsfeld McGrath is a Partner at Hystra and co-founder of the Global Distributors Collective.

Photo credit: Maheder Haileselassie / IWMI

- Categories

- Agriculture, Energy, Finance, Technology