Human Waste as a Value Chain: ‘Sustainable sanitation’ startup has plans to expand throughout Peru and, eventually, abroad

Kyle Poplin: Could you describe the x-runner system and what makes it unique among organizations seeking to improve sanitation in the developing world?

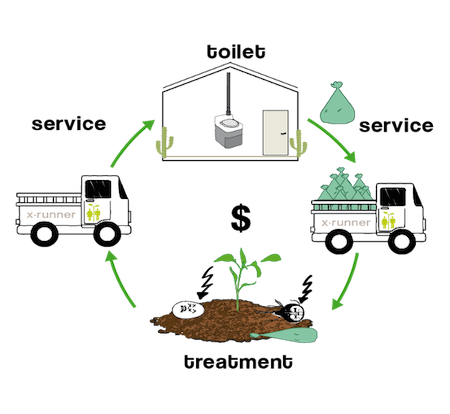

Jessica Altenburger: x-runner provides families who live in the poor urban parts of Lima with an innovative, waterless sanitation system. We launched it in 2012 in Lima. Our solution is based on a for-pay sanitation service: When a customer subscribes, we go by his home and install a waterless toilet. Inside the toilet, the feces, instead of being flushed away, are separated from the urine and stored in a compostable bag.

Once a week, our truck goes by the communities and picks up the compostable bags filled with feces. The collected waste is then transported to the treatment plant where it undergoes a natural treatment and is processed into nutrient-rich compost.

Back in 2012, we were the first enterprise in the sustainable sanitation sector that provided a dry system for the urban realm, at a household level, and that covered the complete value chain – meaning from toilet provision, to waste transport, and waste treatment.

JA: It was a combination of my ideas and a former business partner, Noa Lerner. Isabel Medem (co-founder and CEO) is German-Peruvian and although she lived in Europe most of her life, already had a large network in Lima. … Peru is the country third most affected by climate change. Its capital, Lima, according to the National Environmental Council, is the second driest capital in the world. While Lima’s population of 10 million is growing at 2 percent annually, the city is expected to face severe water scarcity by 2025. Most families in squatter settlements in Lima use latrines, a method that is highly impractical given that most homes are inaccessible for pit-emptying vehicles and the moist mix of excrements weakens the ground, causing buildings to collapse.

(Isabel Medem, far left, and Jessica Altenburger)

KP: I understand you tested your toilets on 60 families in the slums of Lima. What did you learn? Specifically, did you discover any cultural issues or perceptions that had to be overcome?

JA: What we learned was that no matter how poor a family is, the appeal and smooth functionality of a toilet are key for them to be used correctly and often.

KP: How many homes have you equipped so far? What are your short- and long-term goals?

JA: Around 300 families (are customers). This means we’re reaching around 1,500 people with sanitation. Our goal is to expand our sanitation coverage throughout urban Peru and eventually also abroad. For now we are focusing on scaling within Lima and perfecting every step in our processes.

KP: Does x-runner make the toilets? If not, is toilet manufacturing part of any future business model?

JA: x-runner currently imports the toilets from the Swedish dry toilet producer Separett. Separett is the market leader in the sector and offers the toilets to x-runner’s slum customers for a customized price.

KP: How much do people pay per month for the toilets and service? Going forward, do you predict that price will increase or decrease?

KP: How much do people pay per month for the toilets and service? Going forward, do you predict that price will increase or decrease?

JA: People pay $12 monthly for the service. They also pay a $30 one-time toilet installation fee. The price will eventually decrease as demand is really picking up.

(This x-runner graphic, right, highlights the process: Feces is collected in a tank underneath the sitting platform while urine is directed into the ground or in an additional container. ?A service truck picks up the feces once a week and t?akes it to a composting facility for processing?. Within two months pathogens are removed and the compost is turned into nutrient-rich soil.)

KP: Do you use local people to pick up the waste once a week, turn it into compost and sell the compost? Are they relatively well-paid? How big a part of the business model, and mission of x-runner, are those local employment opportunities?

JA: We are an “all-locals team” – except me. Many of our employees come from low-income areas. They are all well paid and officially employed – they receive all their social benefits.

The employment of locals was never an official part of the business model, but just a logical decision. And it is surely aligned with my and Isabel Medem’s ideals to empower low-income families and especially women.

KP: What have been the most pleasant and disheartening things you’ve learned starting a social enterprise in an emerging market? What advice would you give others who want to follow in your footsteps?

JA: The most pleasant aspect is to see how a simple solution can impact families’ lives drastically – families often approach us and tell us how the toilet has changed their lives. There is no better motivation for the entire team than receiving such wonderful feedback. It is disheartening for us to still have to fight for funding and support for our cause because sanitation is not an attractive enough topic to many companies, organizations and private individuals. Somehow, many have difficulties understanding the enormous health consequences bad sanitation can cause and how important it is for the well-being of all of us. … You have to approach this market with an open and flexible mindset. Our target market is still a rather unknown market with a very under-researched spending behavior. We work very much with a trial and error approach and adjust our service and product regularly.

Kyle Poplin is editor of NextBillion Health Care.

- Categories

- Health Care, Social Enterprise, Technology