Keeping Up with the Indians: Exploring emerging practices in a health care innovation powerhouse

Extending health services to the 350 million living below the poverty line in India is not an easy task.

These individuals are spread across the country’s massive rural terrain and are often condensed in its urban centers. As a result, India has become a vibrant testing ground for health market innovations and new ideas to meet the health needs of its large and diverse population.

While India continues to experience economic growth, it faces a number of public health challenges, including an evolving disease burden, a sizable rural population, and a large but unorganized private health sector. According to WHO estimates in 2010, approximately 71% of all spending in health care was private, but about 86% of this spending was out of pocket, which risks pushing the poor further into poverty. In the midst of these trends, non- and for-profit healthcare organizations are testing new methods to leverage public and private resources to meet the health needs of the poor.

A Look at the Facts

The private sector represents a diverse set of health organizations in India that are using a variety of business models to address different health concerns. Many of these organizations are using innovative models to improve the way private health care is being delivered to the poor. What we know from the CHMI database is that at least 118 programs—many identified by the Hyderabad-based research organization ACCESS Health International—are employing innovations that increase quality and efficiency, lower costs, and/or improve access to care.

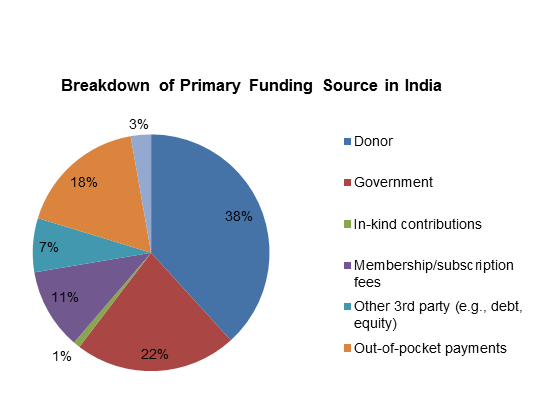

Similarly, 120 programs use models that better organize the otherwise fragmented delivery of care, and 93 programs facilitate health financing. According to the database, most programs profiled rely on some external funding for their operations. Of the 256 CHMI-profiled programs in India, at least 86 are receiving donor support, 52 are receiving some financing from the government, and over a dozen have secured debt or equity investments from financiers.

Promising program models emerging from India include:

Social franchising

In the unorganized landscape of private health providers, patients may struggle to find those providers that meet their price point without compromising quality. The presence of social franchises in India helps patients navigate the complicated health market and better identify quality care, since social franchises provide standardized training and branding for each of their providers. For example, the organization Janani strengthens rural health providers to deliver non-clinical family planning services and brands them as ‘Titli’ or “Butterfly’ centers, making them easily recognizable. Patients needing further clinical services are referred to Janani’s Surya clinics, which provide high-quality and low-cost family planning services. In addition to functioning in the private sector, social franchising has also emerged as an area of interest in India’s government health policies.

Mobile clinics

Mobile clinics are one way to provide health care to the country’s hard-to-reach populations who live beyond the reach of brick and mortar health clinics. In Madhya Pradesh, Deen Dayal Chalit Aspatal uses GPS-enabled vans staffed with a doctor, nurse, lab attendant and pharmacist to provide basic health care to rural populations. Based on the success of mobile health programs, the state government has decided to incorporate mobile medical units into its National Rural Health Mission program.

Information Communication Technology (ICT)

ICT plays a significant role in India’s health market innovations. Just over a third of the CHMI-profiled programs in India indicate using technology as a core part of their model, with phones and computers being the most commonly used technologies. Programs often use these devices to offer patient help lines, telemedicine programs and clinical decision support software. For example, World Health Partners’ rural SkyCare and SkyHealth Centers are connected to specialized doctors in cities through video-conferencing technology on computers. Bangalore-based Teleradiology Solutions provides radiology services for remote or underserved hospitals in Asia that are unable to provide them on-site. Other organizations are using ICTs in other unique ways. Freedom from HIV/AIDS, for instance, has developed a series of mobile phone games that help reduce stigma toward HIV/AIDS. Smart cards, such as those used by the IKP Centre for Technologies in Public Health, track patient data in electronic health records, and are another promising technological innovation to help programs cope with India’s large dispersed patient population.

Technology is central to many of the 100 programs targeting rural areas. It can help facilitate remote diagnosis of rural patients, make health records at peripheral clinics available to central health providers, and allow providers and patients to access health education and awareness information. These are just a few of the ways that programs targeting rural geographies leverage technology.

Microinsurance

The microinsurance movement in India is driven by state- and national-level government entities, but the private sector is also promoting various microinsurance schemes. Arogya Raksha Yojana, for instance, offers complete cashless services for over 1600 surgeries, and subsidized services for hospitalizations that do not lead to surgery. An individual can receive coverage for Rs. 238 (about US $4.50) per year, while coverage for a family of seven costs only Rs. 1,106 (about US $20) per year.

Left: Outside a WHP SkyHealth Center in Bihar

Public Private Partnerships (PPPs)

PPPs are an important part of the government’s efforts to harness the potential of non-state players in the health system. CHMI’s database includes 51 public private partnerships in India. At least 15 of these programs facilitate health call centers or provide emergency services; others provide mechanisms for state governments to contract specific services from the private sector. And several, such as the partnership between the Mahavir Trust Hospital and the city of Hyderabad and the accreditation of family planning clinics in Bihar, allow NGOs to increase access to specialized services from family planning to cancer diagnosis through publicly endorsed programs.

PPPs allow the government to augment the capacity of its directly administered public health system. Consider the example of Orissa, where the state contracted NGOs to revitalize and operate defunct government health centers.

The Social Enterprise Environment

While the Government of India has traditionally prioritized providing needed health services to the poor through public sector facilities, its attitude towards the private sector is slowly softening. Social enterprises are playing a greater role in extending health services to low-income groups, and the country’s Planning Commission has urged the government to use the private sector to fill gaps in public health service.

Forty-six Indian programs profiled in CHMI use a for-profit model, and the impact investment environment in India is growing. Ziqitza Healthcare Limited is a growing Mumbai-based company providing emergency transportation services in several Indian states. The company’s services are paid for either through government contracts or private spending – as with the ambulance pictured above – through the 1298 scheme.

While social enterprises in health and the ecosystem supporting them are still nascent in the country, there is an ongoing trend to promote organizations that can achieve financial returns and health impact.

The information in this post is just a slice of the activities taking place in the health market in India. As the government continues to promote new health policies and partner with the private sector, more health innovations are likely to take shape.

Editor’s Note: This post was developed with contributions from ACCESS Health International’s director of research Prabal Singh. It was originally published on CHMI’s website, and is republished with permission.

- Categories

- Health Care