Reaching ‘an Emerging Market Within an Emerging Market’: JPMorgan Chase and Omidyar back new impact fund aimed at Brazil’s middle class

It’s an emerging market within an emerging market.

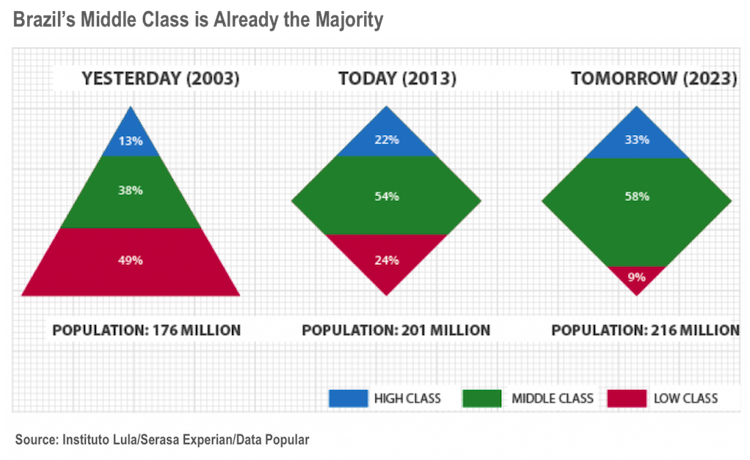

Entrepreneurs who can deliver high-quality basic services on the cheap are rushing to meet the pent-up demands of Brazil’s 112 million lower- and middle-class consumers.

Those entrepreneurs can tap a new source of capital as well: impact investors who are insisting the companies in their portfolios focus on the huge population of Brazilians who make under $10,000 a year.

The investment bank JPMorgan Chase and the Omidyar Network, the combination venture capital fund and philanthropic foundation of Ebay founder Pierre Omidyar, are each committing $5 million to FIRST, a Brazilian fund focused on impact investments. FIRST is, in fact, not the first impact investing fund in Brazil, but it is now the largest, raising $66 million for its first close.

Impact investors are entering Brazil as many international development agencies are leaving. Over the last 15 years, Brazil’s economic growth and social policies have lifted between 40 and 60 million out of poverty. But the country’s overall wealth statistics mask glaring inequality in access to health care, education and financial services.

High-Volume, Low-Cost

Demand from these emerging middle-class consumers means opportunities for entrepreneurs who can make up for low profit margins with high volumes. As a group, Brazil’s new middle class spent roughly $530 billion in 2013.

“They have discretionary spending for basic needs, but access to services to fulfill those needs is lacking in many parts of the country,” says Amy Bell, who led the investment for JPMorgan Chase’s $100 million Social Finance fund. “It’s less about high-margin and more about appropriate margin. The volume you can get through scale is what’s critical to the financial returns and the impact.”

Take, for example, the lines that form outside of public hospitals each morning in nearly every Brazilian city. “Rather than lose a full day’s wage waiting on long lines just to get a consultation scheduled–often for three to six months in the future–people are willing to pay $30 to buy a spot at the beginning of the line, with hopes of seeing a doctor earlier,” says Maria Cavalcanti, a founder and managing partner at FIRST. “Disruptive entrepreneurs see this as an opportunity to provide same-day, high-quality health care services for that $30. And people are willing to pay.”

Cavalcanti returned to Brazil from New York in 2008 with the AVINA Foundation, which funds sustainable development projects across Latin America. She saw a gap and an opportunity. Social programs were boosting the household income of average Brazilians. Last year’s World Cup and next year’s Olympics meant new stadiums, ports and airports. A new breed of VC-backed backed companies catered to the country’s elite.

Yet, the country still faces a shortage of 5.8 million housing units. Even with universal, government-funded healthcare, Brazil has only 1.8 doctors per 1,000 people, compared to 3.2 per thousand in neighboring Argentina (and 6.7 in Cuba). At least 40 percent of the population has no bank account. Brazilians on average attend only 7.4 years of school, compared with 11.3 years in countries at a similar level of development.

“It’s crucial to focus on basic services and products,” Cavalcanti says. “Today a low-income family may finance a flat-screen TV but need to use the box it came in as a roof.”

Cavalcanti was convinced a private investment strategy focused on Brazil’s huge and underserved population could both reduce inequality and deliver competitive financial returns. She found a like-minded partner in Marcus Regueira, a pioneer of Brazilian venture capital and a founding partner at FIR Capital, who had 25 years of investing experience. Both partners are from Brazil’s often overlooked northeast. FIRST has offices in Recife, Belo Horizonte and São Paulo, widening their footprint beyond the crowded southeastern business hubs.

As one of the few women in a senior-level position in the Brazilian VC industry, Cavalcanti can point to research that suggests women-led venture funds outperform the market as a whole. FIRST is targeting growth-stage companies, generally with revenues under $100 million, and forecasts rates of return that are competitive with mainstream venture funds.

Still, raising the fund’s capital was a long effort. Omidyar Network committed first, in 2012, followed by JPMorgan Chase. In the end, 11 investors came on board including quasi-public development funds, such as the U.S.’s International Finance Corp. (IFC), France’s Proparco and Germany’s DEG. Social-impact foundations, such as the Halloran Philanthropies and Calvert Group also came in. The IFC’s $15 million investment was FIRST’s largest.

Brazilian investors have so far largely remained on the sidelines.

Lead investors

“Brazil is between a rock and a hard place,” says Eliza Erickson, who joined Omidyar in 2011 to expand its investments in Latin America. Too developed for traditional development agencies, Brazil’s tax regime, operating environment and foreign-investment rules scare off many institutional investors. Even by emerging-market standards, raising FIRST’s fund took a long time, she says. “We stuck with it. We knew it was going to happen eventually.”

Erickson and Bell worked together to bring in additional investors and conducted due diligence together. The two women joined Cavalcanti and Regueira on five days of site visits to potential investees. JPMorgan Chase’s finance expertise complemented Omidyar’s development experience. “We are interested in financial returns as a demonstration effect, to expand the wallet,” Erickson says. “We looked to them to think about the regulatory market and the capital markets environment.”

FIRST is not Brazil’s first impact fund. That would be Vox Capital, an early-stage investor which made its first impact investments in 2009, closed a first fund of $40 million in 2012. According to Bain Consulting, 20 or so funds in Brazil raised about $300 million for impact investments between 2008 and 2013, part of a 12-fold increase in committed capital, to $2 billion, across Latin America. The Brazilian funds together have made 68 investments.

One is ToLife, a Belo Horizonte-based technology firm with a triaging system to speed service at hospitals and clinics and cut both mortality rates and waiting times. Vox led ToLife’s Series B round last April to help the company expand to facilities serving Brazil’s poor. The product is now used for 150,000 screenings a day in 5,000 health facilities around Brazil.

“Wealth is about more than income. It’s also about access to high quality services,” says Daniel Izzo, Vox’s founder and CEO. A company like ToLife, he says, “reduces inequality by delivering a high quality product to the rich and poor alike.”

FIRST has identified more than 400 companies that fit their dual impact and financial criteria. The team considers 30 to be qualified, is in talks with four and hopes to make its first investment this spring. FIRST is planning to make 10 investments in companies that each have potential to reach at least one million low-income individuals.

“Entrepreneurs are well-served to understand the unique demands and dynamics of the emerging middle class by performing primary market research and developing tailored solutions rather than to make assumptions based on other demographic segments,” says Cavalcanti.

FIRST’s partners pressed for social-impact incentives to be included in their compensation, but the complicated structure worried JPMorgan Chase’s Bell and other investors. Instead, the fund will monitor the number of people reached through their investments and verify that they are within lower income brackets. The fund will measure quality, price and accessibility to ensure the products and services meet real needs.

More than 20 organizations in Brazil have created a Brazil Social Finance Task Force as an informal affiliate of an effort by the G7 industrial countries, to press for policies to increase the flow of capital to impact funds and social ventures.

“There’s very little philanthropy in Brazil and though the government spends significantly on social programs, there’s little innovation,” says Celia Cruz, one of the leaders of the task force. “Impact investing is arriving to this context, with the ability to fund innovation and address problems at scale.”

Editor’s note: This post was originally published on Impact Alpha. It is cross-posted with permission.

Dennis Price is a social impact strategist who works with mission-driven investors, organizations, and entrepreneurs to enhance, measure, and communicate their impact.

- Categories

- Impact Assessment, Social Enterprise