All About India : A Health Care Market in Transition (Part 4)

Editor’s Note: This is the final post in a four-part series on developments and challenges in Indian health care. Other posts include:

- Part 1: Zeena Johar discusses growth areas in Indian health care, and a potentially game-changing development that may be on the horizon

- Part 2: Zeena Johar’s insights on addressing the provider shortage in India and reaching rural markets

- Part 3: Johar’s tips for dealing with quacks, creating a market for primary care, and developing an effective business model

?This post was originally published at YourStory.in, and was adapted and republished with permission.

India’s health care system is at a crossroads.

The country’s population is aging faster than expected. In 1980, the country’s median age was just 20 years – it will be 31 by 2026. Between 2000 and 2050, the number of people between 60 and 80 years of age will increase by 326 percent.

What’s more, lifestyles are increasingly sedentary, and people’s diets have become significantly less healthy.

Due to these changes, the incidence of lifestyle and age-related diseases like diabetes is growing rapidly. And the health care system as currently structured is ill-equipped to respond.

Managing India’s demographic and lifestyle changes will require a transformation of the health care ecosystem. If this transformation doesn’t occur, the country’s fragile health care system is at serious risk.

The impact on low-income Indians

The problems facing India’s health care system have a greater impact on the poor. The unequal geographic distribution of doctors and hospitals makes it difficult for low-income families to access quality medical facilities. Eighty percent of doctors, 75 percent of dispensaries, and 60 percent of hospitals are situated in urban areas – making quality health care virtually inaccessible to people who live in remote areas. And dramatic increases in the cost of care have further limited the options for low-income Indians.

Without access to quality, affordable care, a low-income family will often delay going to the doctor and make do with local quacks until their condition deteriorates to the point where more serious medical interventions are needed. Not only does this increase the overall cost of treatment, it also causes a loss of wage resulting in a major financial setback to the family. This can lead to a family member dropping out of school to seek a job, or other adverse lifestyle changes. Nearly 39 million people fall below the poverty line each year due to health-related expenditures.

The three biggest problems

There are three overarching problems that plague India’s health care sector today, and that must be addressed in response to patients’ changing needs: quality, access and affordability. These problems are exacerbated by:

2. Poor medical infrastructure: In 2011-12, India’s central and state governments together spent only about 906 billion rupees – approximately 1 percent of GDP – on health care. The government’s 12th five-year plan proposes to increase health care spending to 1.6 percent of GDP, ignoring the Planning Commission’s recommended health care spending rate of 2.5 percent of GDP. This has had a direct impact on India’s primary health care centers, sub-centers, community health care centers and direct hospitals, which have fallen woefully short of the numbers of people they are expected to serve. In community health care centers, for example, this shortfall ranges from 33%- 91 percent across Assam, Bihar, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal.

3. Poor health insurance resulting in a higher share of private expenditures: Due to poor insurance penetration in India, Indians pay 60 percent of all health care expenditures out-of-pocket – comparable to poorer countries like the Central African Republic (63 percent), Nigeria (62 percent), Bangladesh (65 percent) and Vietnam (58 percent). People in the United States (12 percent), United Kingdom (10 percent) and Germany (13 percent) spend far less because of better social security coverage, deeper insurance penetration and higher state expenditures on public health. Although India’s health insurance market is one of its fastest-growing segments, only 15 percent of people are covered under health insurance. Only 2.2 percent are covered under private health insurance, of which only 10 percent covers rural people. So there is a tremendous market to be tapped.

Demonstrated solutions

In spite of the seriousness of these challenges, there are reasons for optimism. Here are a few examples of what’s working:

- Building hospitals beyond the cities: Vaatsalya Healthcare has focused on setting up hospital networks in cities and towns with under one million in population. Each of Vaatsalya’s 17 hospitals provides care across specialties in addition to general medicine, trauma, and other services like pharmacy and diagnostics. Vaatsalya is led by two young doctors, Dr. Ashwin Naik and Dr. Veerendra Hiremath, who conceptualized the idea when they were students at Karnataka Medical College. Vaatsalya has received a total of $17.5 million from Aquarius Investments, Aavishkar, Seedfund and Bamboo Finance.

Devices that improve doctor efficiency: Forus Healthcare enables a minimally trained technician to detect an eye ailment using an ophthalmic device called 3nethra. It can detect five ailments that cause 80 percent of all blindness. 3nethra can be deployed in remote locations for a fraction of the cost of other devices. Given that close to 90 percent of all blindness is preventable, widespread awareness and early detection are important in reducing it. (Right: a 3nethra ophthalmic device)

Devices that improve doctor efficiency: Forus Healthcare enables a minimally trained technician to detect an eye ailment using an ophthalmic device called 3nethra. It can detect five ailments that cause 80 percent of all blindness. 3nethra can be deployed in remote locations for a fraction of the cost of other devices. Given that close to 90 percent of all blindness is preventable, widespread awareness and early detection are important in reducing it. (Right: a 3nethra ophthalmic device)

- Remote diagnosis: Neurosynaptic Communications provides affordable telemedicine solutions that enable remote communication via video and audio, and remote monitoring of vital stats like heart rate and blood pressure. The company has nearly 450 rural centers reaching nearly 7,000 villages.

- Accessible diagnostics: Achira Labs, a Bangalore-based diagnostic start-up, is building a micro-fluidic platform that provides point-of-care diagnostics. Achira’s platform helps patients gain access to diagnostics and receive therapy in the same session. Achira Labs has developed ACHIRA 2000, a device that can be stationed on a table top and requires minimum space. This device is battery operated and easily transportable, and it requires minimal input from technicians, transforming the economics and treatment frameworks for medical conditions. Achira is also developing a fabric-based diagnostic system that uses a silk fabric with appropriate reagents to detect ailments.

- Immediate health care finance: The Bangalore-headquartered microfinance institution Ujjivan Financial Services offers emergency loans to its customers, and has created processes that allow for loan approval and disbursement within hours. And a stealth mode start-up located in Mumbai has piloted financing treatments in a large hospital, and has gotten promising results without a single default in payment.

Low-cost solutions replacing specialized equipment: Embrace provides low-cost infant warmers aimed at regulating the temperature of premature and delicate newborns. The warmers look like miniature sleeping bags, and they incorporate a phase change material which stays at a constant temperature for up to six hours. This affordable solution maintains premature and low birth weight babies’ body temperature to help them survive and thrive. (Right: an Embrace infant warmer)

Low-cost solutions replacing specialized equipment: Embrace provides low-cost infant warmers aimed at regulating the temperature of premature and delicate newborns. The warmers look like miniature sleeping bags, and they incorporate a phase change material which stays at a constant temperature for up to six hours. This affordable solution maintains premature and low birth weight babies’ body temperature to help them survive and thrive. (Right: an Embrace infant warmer)

- Building specialty chains that offer high-quality, accessible care: Of the 39 million blind people in the world, a third reside in India. In 2002, Vasan Eye Care started its first hospital in Trichy. Since then, it has grown to become India’s largest eye care network, with 112 centers across the country. Vasan Eye Care provides comprehensive ophthalmic treatment through a large network of centers, increasing access and bringing quality care to smaller cities and towns.

- Insurance innovations: Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY) is a state-run insurance scheme that relies on third-party administrators and technology to deliver cashless health insurance for hospitalization in both public and private hospitals. The RSBY has enrolled 30 million families across 25 states, making it one of the largest health insurance schemes in the world.

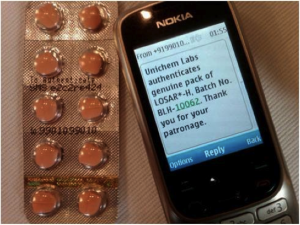

Anti-drug counterfeiting solutions: PharmaSecure has developed a system that uses a track-and-trace system deployed through SMS authentication of codes. A patient can send PharmaSecure the SMS of a unique number present on the medicine, and will receive a notification of whether the drug is fake or authentic. This provides a simple and cost-effective solution to the dangerous and massive problem of counterfeit drugs – especially in developing countries. In October, PharmaSecure imprinted secure verification on its 300 millionth package, and it is currently eyeing the global market for expansion. (Right: PharmaSecure’s system at work)

Anti-drug counterfeiting solutions: PharmaSecure has developed a system that uses a track-and-trace system deployed through SMS authentication of codes. A patient can send PharmaSecure the SMS of a unique number present on the medicine, and will receive a notification of whether the drug is fake or authentic. This provides a simple and cost-effective solution to the dangerous and massive problem of counterfeit drugs – especially in developing countries. In October, PharmaSecure imprinted secure verification on its 300 millionth package, and it is currently eyeing the global market for expansion. (Right: PharmaSecure’s system at work)

Though the challenges facing India’s health care system are vast, solutions do exist. The time to pursue them is now – before changing demographics make these problems spiral out of control.

Disclosure: Unitus Capital has an investment banking relationship with Neurosynaptic Communications. These authors’ personal views do not necessarily represent those of Unitus Capital.

- Categories

- Health Care, Social Enterprise, Technology

- Tags

- public health