A Best Practice in the Making? How Dominica is Building the World’s First Climate Resilient Nation

Hurricane Maria made landfall on the southwest coast of the Commonwealth of Dominica at 9:35 p.m. on September 18, 2017. It was a Category 5 hurricane, with 220 mph wind speed and even higher gusts. The scale of devastation left in its wake was unprecedented:

- 93% of the country’s 72,000 population was impacted

- 65 people perished

- 90% of homes and crops were damaged or destroyed

- 24,000 people became borderline food impoverished

- 43 of out 44 water systems were destroyed

- 90% of the population lacked access to power for four months

- Five out of 11 police stations and five out of eight fire and ambulance stations were significantly damaged

- Six major bridges were severely damaged, making it very difficult to circumnavigate the island.

In all, the damages and losses amounted to US $1.3 billion – 226% of Dominica’s gross domestic product – making this the world’s worst environmental disaster to date, in terms of relative economic impact.

Defining a Climate Resilient Nation

Five days later, on September 23, Prime Minister Roosevelt Skerrit addressed the 72nd United Nations General Assembly in New York. In an impassioned speech, he declared this an “international humanitarian emergency,” and boldly promised to rebuild Dominica as the world’s first climate resilient nation.

In March 2018, the Climate Resilience Execution Agency for Dominica (CREAD) was launched, funded by the Governments of the United Kingdom, Canada and Dominica, with an initial four-year mandate to catalyze the country’s journey towards this goal. Chief executive and operations officers took their positions that November, just before Dominica’s Climate Resilience Act was passed unanimously by Parliament a month later. By April 2019, a staff of 17 were in place.

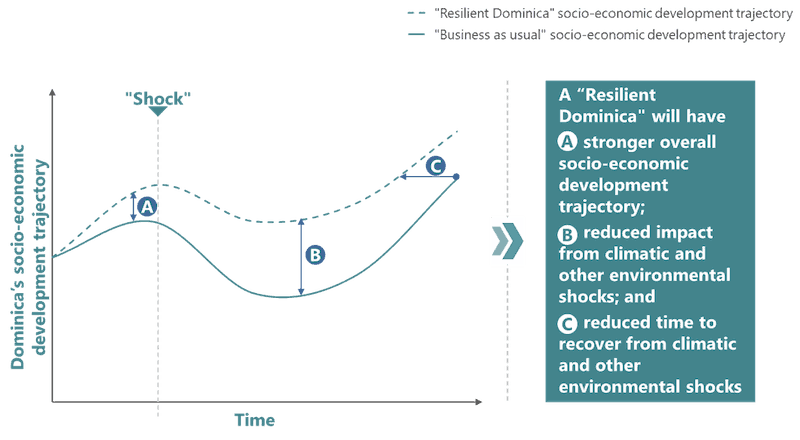

The Climate Resilience Act required CREAD to play both strategic and operational roles—i.e.: to develop a full Climate Resilience and Recovery Plan and implement large, complex reconstruction efforts. It established the agency’s objective of significantly reducing the impact and recovery time of climatic and other natural shocks, as well as boosting the overall socioeconomic development trajectory of the country. With those goals in mind, CREAD set about defining what would constitute a Climate Resilient Dominica (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Defining a Resilient Dominica, from the upcoming Climate Resilience and Recovery Plan 2020-2030

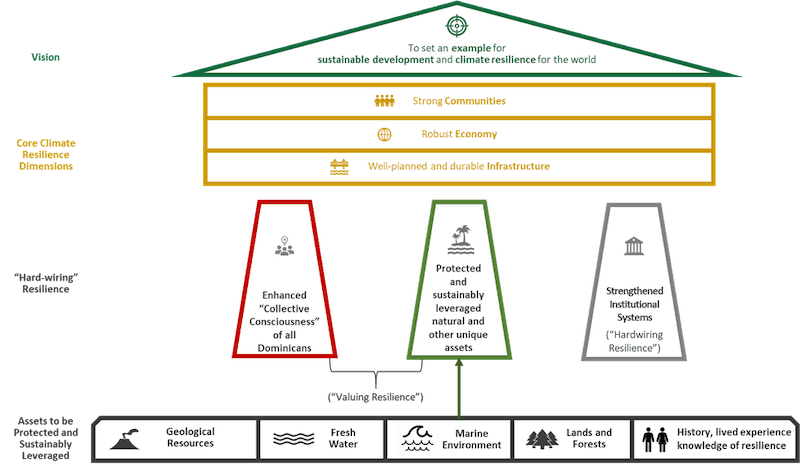

While a number of reconstruction entities have been established in the Caribbean in the wake of Hurricanes Irma and Maria, the approach that Dominica is taking is notably holistic, going beyond mainstream approaches that typically consider either only socio-ecological, infrastructure design, or project finance aspects of resilience. In its Climate Resilience and Recovery Plan, the country fundamentally requires:

- Strong communities, comprised of resilient—i.e.: healthy, educated and safely sheltered—individuals;

- A robust economy, with diversified sectors, business continuity plans, and access to finance and affordable, adequate insurance;

- Well-planned and durable infrastructure, covering both where and how structures are built – something that must support (and not precede) the imperatives listed above.

Furthermore, CREAD stipulates three prerequisites for hardwiring resilience, namely:

- Protecting and sustainably leveraging natural and other unique assets: For instance, Dominica has abundant fresh water, a pristine marine environment, and geothermal resources with potential for domestic use and export to neighboring islands. It’s also home to the last remaining Kalinago people, whose knowledge of the biosphere has been critical for designing resilient structures;

- Strengthening institutional systems, covering policies, plans, procedures, structures and capacity to enable the government to maintain the agenda that CREAD is kick-starting for decades to come;

- An enhanced collective consciousness, which emphasizes the need for every citizen to do their part to reduce environmental, social and economic vulnerabilities, and to help rebuild a country they are proud of (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Dominica’s Resilience Results Areas, from the upcoming Climate Resilience and Recovery Plan 2020-2030

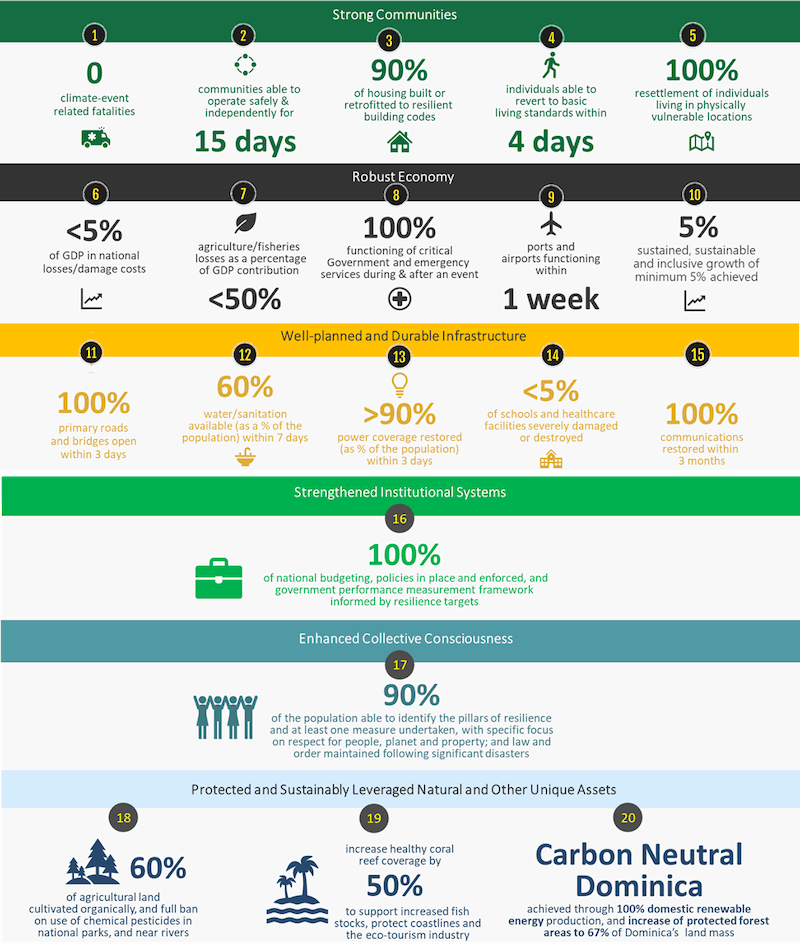

Focusing on these six areas, Dominica articulated 20 Resilience Targets (see Figure 3 below) that have guided the development of a series of specific initiatives to be delivered by 2030. Working closely with government ministries and the private and social sectors, the country outlined and detailed some four dozen initiatives that aimed to significantly contribute to delivery on these targets, giving priority to those that will likely have the greatest impact, with a realistic view on available funding. These initiatives were broken down so as to provide ministries with clear guidance on what needs to be achieved, and by when, in order to stay the course. The total cost of the initiatives is estimated at US $4.5-5 billion. Based on current expenditures and government estimates, it is expected that Dominica could finance up to half of the required investment. A combination of grants, highly concessionary financing and commercial investment will be needed to provide the rest.

Figure 3: Dominica’s 2030 Climate Resilience Targets, from the upcoming Climate Resilience and Recovery Plan 2020-2030

Moving Past ‘Business as Usual’

Recent data suggests that as many as 300 million people could be at risk of rising sea levels and storm surges by 2050. Yet to date, the climate adaptation agenda, while widely touted as critical, remains constrained by a largely business-as-usual approach to national budget setting. That is, short-term political priorities trump what is essentially a long-term planning imperative — at least in many small island states. With this in mind, one of Dominica’s targets (and one of its top 10 resilience priorities) is the revision of the budget allocation methodology: This will be aimed at defining critical policies and enforcement mechanisms, and implementing an enhanced public sector performance management framework that allows the government to more effectively “manage by objectives.” The significance of this cannot be overstated, as it means that the government is walking-the-talk in terms of resource apportionment to projects that have been specifically designed to deliver on the resilience agenda.

Another critical initiative is the development of a comprehensive Resilient Dominica Physical Plan (RDPP). This will significantly reduce vulnerabilities by imposing an appropriate, data-driven infrastructure response or, alternatively, (re)locating populations and assets – as well as informing appropriate land-use decision-making (e.g. preventing farmers from removing trees on slopes above 10 degrees, to reduce erosion). This plan will dictate a capital works program for the coming decade, providing both multi- and bi-lateral development partners with a “menu” of critical interventions to finance or otherwise support, e.g. with technical assistance.

The RDPP will also provide clarity to the private sector on areas zoned for residential, commercial and other development, and outline the major works programmes scheduled to be delivered (and, therefore, tendered) and opportunities for investment. This is particularly important, as Dominica – like other small island states – often struggles to attract more seasoned investors, developers and contractors, since project volumes are typically relatively small. By providing transparency about the potential pipeline of activities that will be delivered over the coming three, five and 10 years, regional or international delivery partners can make more informed decisions as to whether they are interested in establishing a presence in the country, on the basis of the potential to aggregate projects.

However, beyond this, there is clearly both room – and urgent need – for the private sector to come to the table in a number of other areas. For example, the Climate Resilience and Recovery Plan’s ResilienSEA Blue Economy Investment Fund, rather than being backed by government, takes a more commercial approach: It provides equity investment combined with a technical assistance facility to support the development of small and medium-sized businesses operating in coastal areas, or dependent on the broader marine environment in sustainable ways. Aiming to provide financial, social and environmental returns, it should be of interest to impact investors.

The country has other natural resources that might be of interest to investors. For instance, Dominica’s artisanal bay oil sector was once estimated to have produced some 85% of the total global supply of this precious commodity, used in high-end fragrances and a range of other products worldwide. The sector employed some 700 farmers, with spillover benefits to several thousand people. But in 2015, Tropical Storm Erika dumped eight inches of rainfall in less than 12 hours and triggered massive flooding and several landslides across the country. Production has since dropped significantly, as the bay leaf-producing community of Petite Savanne was declared uninhabitable due to the devastating landslides it suffered. Regenerating this industry could be transformative, protecting a centuries-old tradition of artisanal bay oil production, and boosting job creation.

The private sector can also contribute to preparedness and post-disaster response and recovery more broadly. Regionally, there are examples of supermarkets being used as food stores during hurricane season, increasing stock during the months of June to November, in return for heightened security and tax incentives. Similarly, framework agreements can be developed with contractors and construction equipment owners, to respond to road clearance requirements automatically after a storm. And major hotel kitchens can be leveraged for the production of food in a post-disaster environment – among multiple other ways in which local companies can contribute tangibly to critical needs.

IN SUMMARY

Dominica faces tremendous climate risks, from sea level rise to landslides, floods and severe wind events. It is also home to nine active volcanoes and sits in a seismic zone. But with the right support from the public, private and non-profit sectors, this tiny island could serve as an incredibly important pilot case for developing innovative solutions to both climate resilience goals and broader social and environmental sustainability imperatives – and demonstrating how to deliver them.

Pepukaye Bardouille is Chief Executive Officer and Colin Scaife is Chief Operating Officer of the Climate Resilience Execution Agency for Dominica (CREAD).

Photo courtesy of Skybluesrich.

- Categories

- Environment