Achieving an Equitable COVID-19 Recovery Through Safe Housing: Why it’s Time for Financial Institutions to Step Up

Mrs. Vee is a micro-entrepreneur who makes her living collecting trash in Hanoi. Since the pandemic began, a large part of the waste she collects has been used personal protective equipment. Miriam is a laboratory technician in a district laboratory in Uganda. She has been engaged in testing samples for COVID-19 since the virus struck. Juan is a bus driver in Jalisco, Mexico. Because of the health crisis, he is now responsible for keeping his bus sanitized. (Note: These profiles are composites of people the author has met.)

What do these workers have in common? It’s not only that they have all been impacted by COVID-19. After all, who among us hasn’t? It’s that, like over 1.5 billion people, they go home every day to a crowded house, often with limited sanitary amenities like flush toilets or handwashing facilities. There, they are at increased risk of contracting or spreading the virus. These essential workers, who earn close to or below the minimum wage, are the key to keeping economies working until a vaccine is available to all. And there is growing awareness that their role in recovery from the pandemic is compromised without safe housing.

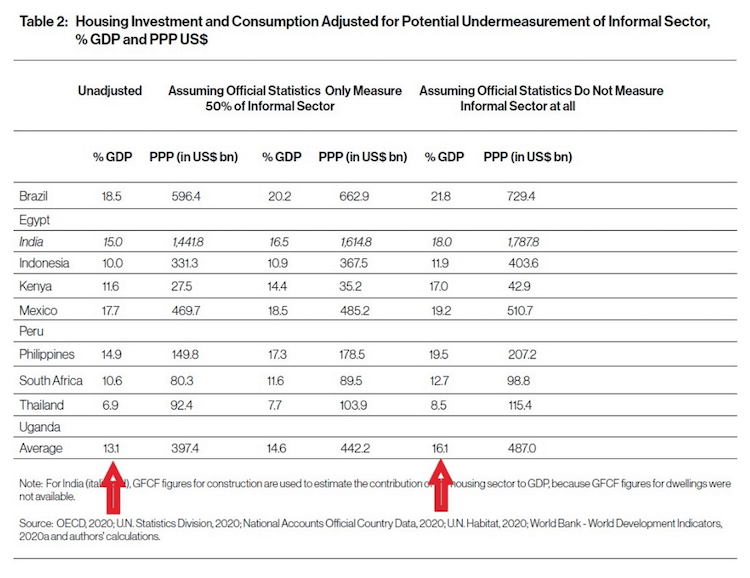

The “Cornerstone of Recovery” report, by University of Washington Professor Arthur Acolin and Professor Marja Hoek-Smit of the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, finds that investment in housing provides a greater economic impact than is currently reflected in national data. In fact, only eight of the 11 emerging economies studied capture sufficient data about their housing markets to calculate housing’s contribution to GDP. Accurately counting informal-sector housing services across these eight economies could add an average of 3% to each country’s GDP, as currently measured.

There are significant differences in national data collection methodologies, so it is difficult to predict the true shift in GDP numbers until international norms are adopted. Still, the implication is that protecting frontline workers by improving their homes will provide a larger than expected economic boost, while also improving their safety and ability to keep working. In other words, it could provide an equitable social and economic recovery. This finding is echoed in a survey of Australian economists, who believe housing (in this case, social housing) is the best of the 13 recovery options they assessed, as it provides a short-term economic boost along with an opportunity for long-term impact.

Fortunately, solutions for better housing exist, and the private sector needs to get on board. The World Bank’s Simon Walley wrote a COVID-19-focused foreword in the new book “Taking Shelter: Housing Finance for the World’s Poor.” In it, he argues, “A rapidly rebounding housing sector can play a vital role in reviving economic growth and job markets. This is especially true in emerging economies where job multipliers for housing are higher.” He also points out that key parts of the New Deal, passed to help the United States recover from the Great Depression, focused on stimulus for housing construction as a means to boost economic activity. Walley claims a similar step could help “heal some of the damage of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

COVID-19 Response Funding and Housing Finance

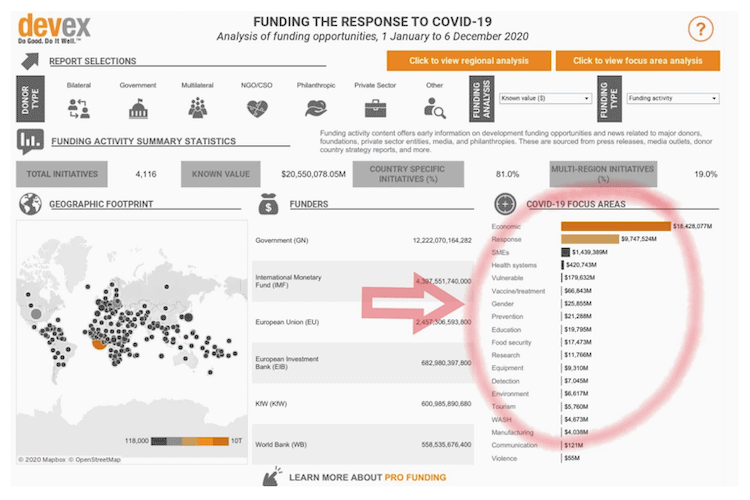

Unfortunately, the funders of COVID-19 responses have not yet heard this message. The global development platform Devex has been tracking where the over $20.5 trillion in COVID-19 response funding is being targeted, and housing is not among the 17 focus areas.

The largest portion of COVID-19 response funding, making up $12.2 trillion, is controlled by governments. Is it possible that governments are using some of these funds for housing? Unfortunately, it seems not many have. The Cornerstone Report authors sifted through the 196 countries analyzed by the IMF to understand their COVID-19 responses and found only 22 that explicitly included housing in their plans. Some of these plans are non-specific, such as Guatemala’s “fostering low-income housing” goal. Others provide clues into what may work elsewhere: Egypt is offering a preferential interest rate for housing loans; India has introduced refinance facilities for housing finance companies; and Mexico is offering low-interest housing credits to government workers.

These measures all flow through the financial system, and the Cornerstone Report makes clear why: “Finance, unlike land, is relatively easy to mobilize and can be distributed through banks and other financial institutions … However, the small scale and lack of depth of the housing finance sector in developing countries prevents stimulus programs based on finance from serving middle and lower-income markets more broadly.” In other words, once liquidity is available, financial institutions — along with other financial services providers like mobile money and electronic payment platforms — must be ready and able to deliver the finance needed to help low-earning essential workers make their homes safer. However, many of these workers are among the 37% of the global population still unserved by financial institutions.

Solving Home-Related Financial Inequality

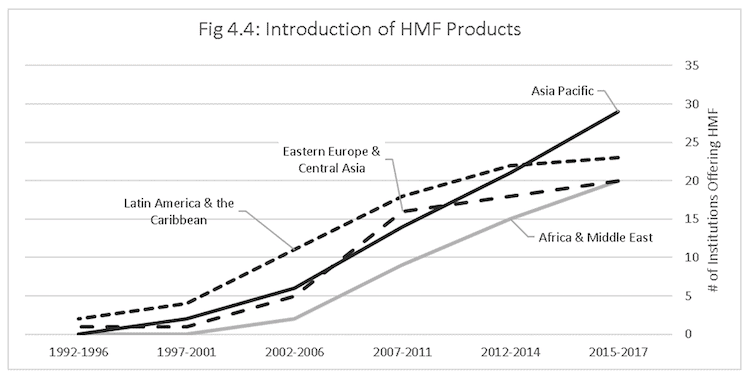

Thankfully, in recent years, innovations in both mortgage and non-mortgage housing finance have made it easier for financial services providers to reach a broader clientele and solve some of these home-related financial inequalities. As Sandra Prieto and Patrick Kelley point out in “Taking Shelter,” the number of financial institutions offering housing microfinance nearly doubled between 1996 and 2017.

The work of Habitat for Humanity’s Terwilliger Center for Innovation in Shelter and Finance (disclosure: I have worked with Habitat for Humanity on other projects) has been instrumental to that progress. It has produced a free product development handbook specifically for housing microfinance — the type of loans most appropriate for making small, incremental home improvements that can have major impacts on health and quality of life. The Center has also worked with over 100 financial institutions across the globe, teaching them how to lend to low-income people for housing.

The mortgage finance industry has also made great strides in finding ways to serve low-income people, and technology is helping. In India, Aavas Financiers Ltd. uses data to offer mortgage loans to borrowers who may not have traditional sources of employment verification, like pay slips. For example, Mrs. Vee, the micro-entrepreneur from Hanoi mentioned above, operates in an entirely cash economy, but she probably makes more than minimum wage. This could qualify her for a loan from an institution like Aavas.

Making housing products available to these borrowers requires commitment and capacity, but capital, as they say, is king. Financial institutions entering a new market often look for funding and some type of risk sharing before making the leap. Here, again, options have appeared in recent years that didn’t exist before. Funds like MicroBuild, managed by Triple Jump in the Netherlands, offers loans to financial institutions engaged in housing finance for low-income households. The fund provides bespoke technical assistance to help borrowing institutions manage risk, including housing-specific training in credit risk management, information system adaptation and marketing. Broader housing liquidity facilities like the Kenya Mortgage Refinance Company are beginning to lower rates and make mortgage funding more stable. While this stability is welcome and should create more mortgage funding availability generally, funding institutions are also working to ensure the benefits of a stronger value-chain flow to lower-income earners. For instance, development finance institutions behind these lenders often impose caps on the size of the loans that lenders who accept their lowest-cost funding can offer to their customers, making loans for smaller homes more viable and likely to be offered.

These are just a few examples of how private-sector financial institutions can play a role in improving homes for essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, keeping them safe at home until we are all vaccinated, and increasing their resilience for the next pandemic. The hurdles that have previously kept these financing options away from low-income households have been greatly lowered, and it is time for more financial institutions to join the cause and ensure an equitable social and economic recovery.

Patrick McAllister is a consultant and recognized expert in affordable housing finance.

Photo courtesy of UN Women Asia and the Pacific.

- Categories

- Coronavirus, Finance