From COVID to Foreign Aid Cuts: How Community-Led Financial Access Can Help Women and Their Communities Weather Crises

When I grasped the implications of the global shift the social impact field is facing, between cuts to foreign aid and U.S. tariffs, I had the same sinking feeling in my stomach that I felt when I realized the scope of the COVID-19 pandemic.

We’re losing things we will not get back.

COVID had a substantial impact on women’s ability to access financial services in many emerging economies — an impact that persists to this day. Now, a new crisis is building, and along with it a growing sense that women’s financial inclusion will be set back once again. As foreign aid diminishes or vanishes entirely, and as macroeconomic uncertainty caused in part by tariff-driven trade wars drives mainstream investors away from emerging markets, financial service providers will receive less funding. There will be less grant funding, less debt funding and less equity. Donor resources, which have become much scarcer since January, will now be focused on life-saving activities rather than on supporting livelihoods through financial inclusion.

In light of this drastic reduction in resources — and the long list of competing priorities that still need to be funded — why discuss financial services right now? Despite the urgency of other global issues, access to financial services matters. Based on multiple studies, including global health data and financial inclusion research, we estimate that for every 1 million people gaining financial access, at least half experience a reduction in health risks linked to premature death, including lack of access to care and poor nutrition in adults, along with reductions in under-five child mortality rates.

The benefits compound when financial services reach women. A synthesis of impact evaluations, such as this study by Nathalie Holvoet, suggests that when 10 new women gain financial access, four additional children are educated, due to increased household investment in school attendance and learning outcomes. Likewise, financial inclusion is associated with reduced rates of child malnutrition; for every 100 women who gain access, approximately seven children are spared from stunting, a key marker of chronic undernutrition.

I mention these statistics because female customers tend to leverage financial services as a means of achieving positive outcomes for their families, which trickle down to their surrounding communities. But the direct impact of financial services on women themselves is also substantial: To take just one example from 60 Decibels’ latest Microfinance Index, “The impact of these loans on women’s financial resilience is particularly noteworthy: 73% of the women we interviewed report an improved ability to cover a financial emergency, with 24% noting a significant improvement.”

Below, I’ll discuss how the effects of the pandemic continue to impact women’s financial inclusion, how history is threatening to repeat itself — and how community-led financial access can offer a solution.

The Ongoing Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Women Borrowers

During the pandemic, the IMF’s Financial Access Survey showed that financial access suffered for both men and women, and that the overall percentage of female loan recipients dropped in a number of markets (after years of advancement). At Kiva, we witnessed a similar phenomenon from our position monitoring investments in approximately 200 financial service providers and social enterprises: We saw female staff turnover at our partners increase dramatically relative to male staff turnover during this period — an issue noted by other organizations in the sector. We inferred that women were unable to work due to their care burdens, meaning women clients had fewer women to interact with at their financial service providers — something that could help account for a drop-off in female borrowers.

Representation matters, and not just theoretically. In reviewing data from Kiva’s impact scorecard — a proprietary tool developed to assess partner alignment with our impact strategy — we discovered that there is a significant positive correlation between an organization having more than 50% of staff identifying as female and other important factors linked to positive social impact. For instance, these organizations performed above the global mean when it came to mission alignment, offering gender-smart products and services, targeting underserved clients, and implementing best practices around transparency and client protection. In other words, women’s presence on staff correlates with better impact practices and policies, which are drivers of positive client outcomes.

But the reduction in female staff isn’t the only lingering effect of the COVID crisis on financial service providers. Earlier this year, several visits to Kiva partners in Jordan and Kenya revealed that some of these providers have not fully recovered from the pandemic in other ways. At multiple microfinance institutions, we observed that group loan products weren’t recovering from the pandemic, even as social distancing ceased.

Over time, I have noticed that, like other consumers, microfinance clients have begun seeking more convenient services as their borrowing options increase in a maturing market. In many cases, this has led to the replacement of group solidarity lending models with individual lending models or smaller group lending models. This shift happens because customers prefer not to take on their neighbors’ credit risk when alternatives are available.

But while this preference is understandable, it also creates an unfair situation that disadvantages women in particular. Although mobile transactions have reduced the cost of providing financial services, underwriting small loans to women (who often hold few assets) remains expensive and labor-intensive. If microfinance institutions can no longer make group lending models work, how can we bring women into the market? How can we ensure that group lending models don’t fade away in favor of high-cost, under-regulated and unscrupulous digital lenders that trap borrowers in a cycle of debt?

Some financial service providers are finding innovative ways to navigate the transition away from group lending, while continuing to make their services accessible to women customers. One inspiring case study featured in Weathering the Storm II — a report on the broad crisis responses of finance providers by the Center for Financial Inclusion and the European Microfinance Platform — comes from Kashf Foundation in Pakistan. To weather a repayment crisis, the institution redesigned its loan products, shifting from group lending to client-centric individual lending. They were able to do this thanks to strong management, mission focus, and debt forbearance and grant funding from the organization’s funders. Though I’m proud of the microfinance sector’s efforts to collaborate in this way during COVID, I can’t say that we consistently provided the kind of support that enabled the thoughtful and ultimately successful strategic transformation witnessed at Kashf.

How Community-Led Financial Access Can Help Address the Current Crisis

Under financial stress, financial service providers will have less money to design products for underserved clients — and less ability to offer products with less favorable unit economics, such as smaller loans (like those to women) or loans with lower interest rates (like those to smallholder farmers). And this financial stress is now a reality for many providers: For example, as part of recent foreign aid cuts, four of Kiva’s partners in Colombia lost capacity-building funding that had been earmarked for the design and delivery of financial services for displaced people. Kiva will be fortunate if we can replace even 5% of that funding, but we will do our utmost to provide whatever support we can, and to learn from our partners as they expand their outreach to displaced populations.

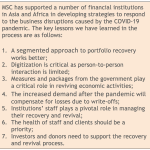

Despite the challenging funding environment and ominous economic trends, we hope to grow our support for displaced people, women and climate-impacted populations over the years to come. I believe we can do this efficiently by applying the lessons we learned from the pandemic, while leveraging our global network of partners and our unique, community-led funding model:

- Amid economic, political and climatic instability, our local partners know more about resilience than any global organization does. Learning from our partners and our peers will help us make the right decisions with the resources available to us.

- Kiva.org’s model, which channels capital from members of the public to organizations and borrowers around the world, was designed with uncertainty in mind. The risk of non-payment by borrowers can be passed on to this community of lenders, who have shown a willingness to increase their average loan amounts during difficult times. This is something Kiva lenders did during the pandemic: Their average deposit in 2021, when repayments were down due to the pandemic, was 14% higher than the 10-year average. So we don’t need to change our model to respond to this moment; we simply need to stay focused on our role in the global financial inclusion industry.

- Our investors and strategic partners have demonstrated strong commitment to the needs of financially excluded people. We trust that our community will remain united around this common goal.

One of the key lessons I took from the pandemic, and will carry forward, is that human beings are resilient. Many microfinance portfolios weathered the pandemic better than those of commercial lenders. Though the sector was hard hit, business resumed quickly with the end of lockdown, though portfolio quality suffered. Microfinance funders also demonstrated an ability to collaborate and remain mission-focused during a crisis: While women’s share of financial access declined overall during the pandemic, the share of women served by financial inclusion-focused impact investors actually increased. Now, once again, we must figure out how to pool and focus our limited resources to protect the gains we’ve made and counter the new decline in funding that supports livelihoods for women, displaced people, climate-threatened communities and marginalized entrepreneurs.

As Kiva’s borrowers struggled to repay their loans during the COVID crisis, which reduced repayments flowing into lender accounts, our lenders generally responded by reaching deeper into their pockets in order to continue lending. While this crisis may or may not play out the same way for lenders, I find comfort and confidence in that lived experience, which demonstrates the power of community-led solutions during a crisis. Kiva lenders and donors can’t come together to replace the vast levels of U.S. foreign aid funding, but we can and will continue to support organizations that operate sustainable models, enabling them to survive and grow, even in times of crisis. Concurrently, we can sharpen our ability to support women’s prosperity and resilience by listening to our partners and our peers.

The opportunity to lead and make an impact is here — and we intend to seize it with urgency and purpose.

Kathy Guis is Executive Vice President, Investments at Kiva.

Photo credit: Shiwa Yachachin

- Categories

- Finance