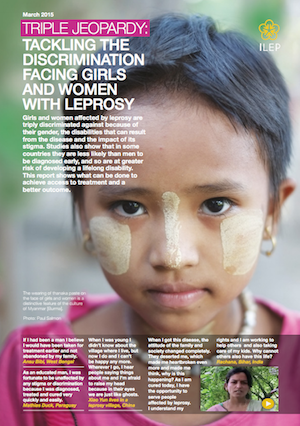

Triple Jeopardy: Report details the discrimination facing girls and women with leprosy

Girls and women affected by leprosy face discrimination on three counts: their gender, the disabilities that can result from the disease and the impact of the stigma surrounding the disease.

The International Federation of Anti-Leprosy Associations published a report, “Triple Jeopardy: Tackling the discrimination facing girls and women with leprosy,” today, just ahead of International Women’s Day on Sunday.

The report warns that the new United Nations Sustainable Development Goals will fail in their aim to “leave no one behind” if discrimination against girls and women affected by leprosy is not tackled. In many countries, the invisibility of women means that the leprosy is not detected, meaning that they do not appear in the World Health Organization statistics. Early diagnosis can prevent permanent disability, but girls and women are often kept indoors and hidden away to avoid bringing the stigma of leprosy to them and their families.

Late detection and diagnosis is caused by the lack of access to information, education and literacy. Early marriage, confinement to the home and the time-consuming domestic tasks required of many can all reduce access to, and involvement in, the wider world.

“What is required is an ongoing educational approach to combat the misinformation and the fear that this generates, much in the same way that was delivered very effectively for the HIV/AIDS epidemic, to help eradicate outdated perceptions.”

Professor Nora Groce, director, Leonard Cheshire Disability and Inclusive Development Centre

View the report here.

View the report here.

The stigma of leprosy can severely affect prospects of marriage and the possibilities of earning an income.

Maksuda lives near to Sirajganj in Bangladesh. She was diagnosed with leprosy and cured with a six-month course of multi-drug treatment. Maksuda’s husband, however, believed that the disease was incurable and highly contagious. He divorced her and left her with nothing. She was forced to move back to her parents’ house with their five-year-old daughter. There was no money to pay for her daughter’s education.

With a small loan from a Lepra self-help group, Maksuda was able to buy a sewing machine and two goats, and later a cow. Within two years, she had sold three cows and had taken a bank loan to start a poultry business. Today, she supplies around 1,600 kilograms (about 3,500 pounds) of chicken to the local market and has bought a computer. Maksuda has a dream to become more independent and offer support to others affected by leprosy.

The ostracism of girls and women damaged by the stigma, directly or indirectly, must be addressed to stop this triple jeopardy. A purposeful and repeated public education programme is needed to stop this stigmatisation because, when stigma is acted upon, it becomes discriminatory.

Anne Kiely is communications officer with Lepra, based in Colchester in the UK.

- Categories

- Education, Health Care