In Defense of Palm Oil: Why We Should Be Supporting the Industry’s Move Toward Sustainability – Not Demonizing It

I read Jim R. Richards’ op-ed “The Ecological Disaster of Palm Oil: Why It’s Time to Embrace Climate-Friendly Alternatives” on NextBillion, and had to respond.

The article made it sound as if all of humanity’s problems would be solved if we would stop using palm oil. That opinion was so far from the truth that I felt compelled to present some facts on palm oil. The reality is far more nuanced than Richards’ article claims.

Palm Oil’s Ongoing Movement Toward Sustainability

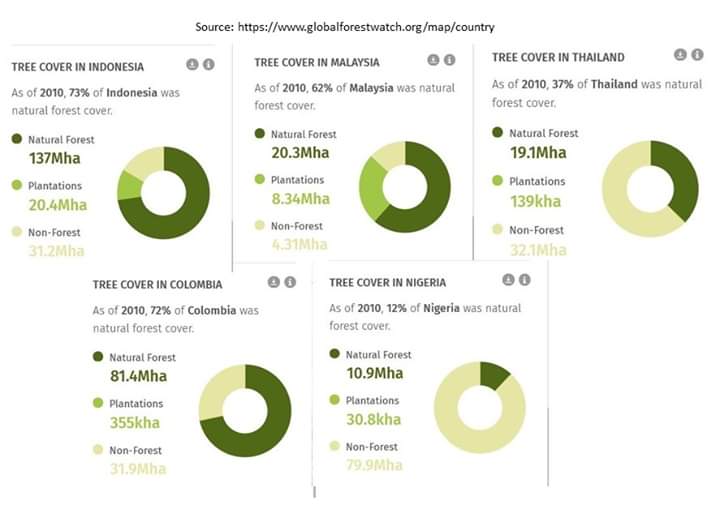

One part of Richards’ argument is accurate: Back in the early 2000s, as palm oil producing countries – especially Malaysia and Indonesia – expanded growing areas to meet a booming global demand, forests were cleared with no concerns for the consequences. Indeed, when the World Resources Institute (WRI) wrote this blog in 2011, the popular narratives about palm oil’s role in land conflicts and wanton deforestation might have been completely true.

But in response to WRI and other global voices that protested the industry’s practices, the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) was formed, with the mission to create a model for sustainable palm oil production. The RSPO is now a dynamic business-to-business scheme providing palm oil buyers with the assurance that producers are maintaining sustainable practices.

The RSPO came under criticism for failing to mitigate unsustainable practices by palm oil producers and (allegedly) working with plantation companies to conceal violations of the RSPO Standard. But whatever its failings, as someone who has worked to hold the RSPO accountable by challenging its members who violate group principles, I have to admit that the organization deserves credit for having sparked the drive towards producing palm oil sustainably. This drive toward sustainability has been picked up by palm oil producing countries, leading to the launch of national certification schemes, including Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO). The MSPO certification scheme has raised the stakes for these efforts, providing a mandatory certification that requires every drop of Malaysian palm oil to be certified as sustainable.

Due to these initiatives, great strides have been taken to address the need to balance development with conservation. But no one has to take the word of the palm oil industry about its moves toward sustainability. Apps released by the RSPO and the MSPO have made it possible for anyone with a smartphone to track the industry. The Malaysian Palm Oil Council is even adopting blockchain technology to further improve transparency. These tech moves are a direct challenge to critics who say the sector has something to hide.

Efforts by the RSPO, MSPO and others have had additional positive impacts, protecting biodiversity and empowering local communities. This can be seen in companies like Sime Darby, one of the largest palm oil producers in the world, which has provided deep funding through the Sime Darby Foundation to preserve biodiversity in places where it works, while making meaningful charitable contributions to local communities.

The scientific community has taken note of this progress, including the University of Gottingen, Germany, which released a report this year finding that “the rapid expansion of oil palm has also contributed considerably to economic growth and poverty reduction in local communities, particularly in Asia.”

The human side of the story on deforestation and palm oil

Despite these developments, the palm oil industry faces a big challenge in telling the other side of the story: how it is bringing better livelihoods to impoverished people in developing countries. The fact that so many people in these countries live on less than a dollar a day may be of little interest to some environmental activists. But the economic benefits of the industry aren’t as easily overlooked by impoverished communities themselves.

The Dayaks of Malaysian Borneo, whose loin-clothed men and topless women were once a popular subject for photographers, are a prime example of this. Their struggles for indigenous rights have not been easy. Where they once had to deal only with land conflicts and discrimination at home, they now have to fight criticisms of the industry that provides many of them with employment, from outside activists who they consider to be antagonists from faraway places. To take one example, in this press release the Dayak Oil Palm Planters Association went as far as saying that “discrimination against palm oil is discrimination against indigenous peoples who depend on the crop for empowerment.”

This was a rare pushback by these small farmers, many of whom I’ve met in my travels researching the palm oil industry. The Dayak oil palm farmers that I know as friends are far too busy working their farms to spend much time on public relations campaigns. But despite the challenges they face, the Dayak culture remains strong, marked by their traditional longhouses and the community spirit that brings extended families together to maintain their farms. Picking out which families are oil palm farmers is easy enough. One need only look for the longhouses with a satellite dish overhead – or for the more enterprising, a 4X4 parked in front. In these farmers’ opinion, they have as much of a right to these signs of progress as anyone else.

Supporting the Palm Oil Industry’s Move Towards Sustainability

Yet as much as producers and other stakeholders in the industry may gripe about the “black campaigns” conducted by international NGOs against palm oil, my view is that they should thank the alarmists and environmental groups for pushing this commodity toward greater sustainability.

That sense of gratitude should be shared even by the organizations and activists that oppose the industry in the hopes of saving orangutans in Malaysia and Indonesia, as the growing sustainability of palm oil production has boosted the preservation of the great ape and its habitat. The governments of both Malaysia and Indonesia – the countries where the orangutan’s habitat is located – have accelerated these efforts, while making substantial investments in direct funding for sustainable palm oil certification programs that enable farmers to continue their work while also protecting wildlife.

In fact, ironically, if Malaysia and Indonesia were to ban palm oil as many of the industry’s critics demand, the result would likely be worse for orangutans and other endangered species. According to Matin Qaim, an agricultural economist at the University of Göttingen and the first author of the study cited above, “… banning palm oil production and trade would not be a sustainable solution. The reason is that oil palm produces three times more oil per hectare than soybean, rapeseed, or sunflower. This means that if palm oil was replaced with alternative vegetable oils, much more land would be needed for cultivation, with additional loss of forests and other natural habitats.”

Producing palm oil sustainably is the only sure-fire way to save the orangutans and their forests. However, this requires the presence of stakeholders with a vested interest in saving them. The solutions proposed by critics like Jim R. Richards would only have a negative influence on their preservation.

Agriculture is a contributor to climate change, deforestation, biodiversity loss and other environmental problems around the world. But farmers and other industry players must be engaged as part of the solution to these crises – not portrayed as the villains. As the International Union for Conservation of Nature reported, saying no to palm oil would merely increase the production of other crops to meet the global demand for oil, displacing rather than halting the biodiversity losses caused by the palm oil industry. No one should make the false assertion that they will be saving the planet when they reject products that use palm oil.

Robert Hii owns and operates CSPO-Watch.com.

Photo courtesy of CSPO-Watch.com.

- Categories

- Agriculture, Environment, Technology