Can You Really Make a Fortune in Bop Health Care? An Interview With Paul Polak

Paul Polak is one of the leading voices in social enterprise, and a man on a mission: to convince the world that socially responsible for-profit business is the best tool for alleviating global poverty.

That belief has formed the basis for his non-profits (International Development Enterprises and D-Rev) for-profits (Windhorse International), and books (Out of Poverty and the upcoming The Business Solution to Poverty).

Polak has distilled his approach to doing business in the developing world to a simple formula:

- Make a “radically affordable” product

- Overcome the challenges of last-mile distribution

- Find a way to scale the business

As we launch the new NextBillion Health Care blog today, I was curious about how this model could be applied to the health care sector. How can a business succeed in BoP markets if it involves the expertise of providers that can’t easily be scaled, or advanced technologies that may never be “radically affordable?” And is for-profit business an ethical way of providing products that people literally can’t live without?

I spoke with Polak recently about these and other questions.

James Militzer: How would you apply the concept of radical affordability to something like an MRI – is it possible to get the price of that kind of technology down to the point where it can be marketed to health systems in under-developed communities?

Paul Polak: You can’t just assume that an MRI is the right technology and you have to get the price down. The problem is how do you diagnose basic illnesses cheaply. [In developed countries] the MRI is used very widely early on in the process, because we have third party insurance. But in a developing country setting, you’ve got to develop all the diagnostic tools that would make the diagnosis without it. And there is an opportunity for literally hundreds of new, radically affordable products that do diagnosis and that are also therapeutic.

I’m not in any way saying that radically affordable technology provides an answer to all of those diagnostic cases – in some cases, you have to go to some center that has an MRI. And I haven’t worked on MRI’s, so I couldn’t tell you how you can design a more affordable one. But I can tell you this: every piece of technology that I have looked at, I’ve been able to come up with something that works through identifying potential tradeoffs, and I’ve been able to cut the cost to 50 percent within a day. Cutting the cost of any technology to 1/5 takes maybe six months.

JM: Can you provide an example of how to identify tradeoffs when designing radically affordable medical technologies?

PP: You have to break it down – what are the most important functions, and how do you make it cheaper? For example, a team of students at Stanford’s class “Design for Extreme Affordability” was looking at incubators. The Western incubator for premature infants costs $4,000, and it is designed to keep the immediate environment of the infant sterile and to help with respiration. But its most important function is to maintain the right body temperature for that infant – you plug the incubator into electricity and there’s a thermostat-modulated way of keeping up the temperature.

PP: You have to break it down – what are the most important functions, and how do you make it cheaper? For example, a team of students at Stanford’s class “Design for Extreme Affordability” was looking at incubators. The Western incubator for premature infants costs $4,000, and it is designed to keep the immediate environment of the infant sterile and to help with respiration. But its most important function is to maintain the right body temperature for that infant – you plug the incubator into electricity and there’s a thermostat-modulated way of keeping up the temperature.

(Left: The Embrace baby warmer, from student project to marketable product – http://www.embraceglobal.org/.)

So the first thing the team did was say, ‘How can we best keep the temperature up?’ And look, we’ve got a problem: in some clinics, there’s no electricity. So one of the students said, ‘Well, why don’t we put the infant in a sleeping bag?’ But all a sleeping bag does is to prevent a loss of the heat already created by the infant. So they fooled around with different materials that release heat at the right body temperature, and it took several months for them to come up with a certain kind of wax. Using a sleeping bag instead of a complex high-tech incubator cut the cost by much more than 50 percent, and that idea came up pretty quick.

JM: With the obvious potential of the health care market in developing countries, why do you think more multinational corporations aren’t pursuing affordable medical technologies on a large scale?

PP: Well, let me answer your question with another question. At the time that Henry Ford came along with the $370 motorcar, all of the cars being made were in the range of $3000, and were basically made for rich playboys. Why didn’t any of the other 150 or so manufacturers think of designing a $370 car?

JM: Maybe they didn’t think that a typical person would ever be able to afford the product.

PP: And they couldn’t make money doing it. So there you go. This isn’t limited to this stage in history, or medical technology. The reason that the multinationals by and large have not invested in this space is because:

- They don’t think they can make a profit from $2 a day customers,

- They don’t have a clue how to design things that are radically more affordable, and

- They don’t have a clue of how to do last mile delivery.

JM: Why should health care companies and entrepreneurs focus on developing markets, in light of the challenges you just mentioned – and how should they address those challenges?

PP: If you really want to make a lot of money, you create a new market. There are 2.6 billion people who live on less that 2 dollars a day, and their biomedical needs remain to a large part untouched – that’s a virgin market waiting to be tapped. There are a huge number of opportunities that are as important in the biomedical field as the introduction of the personal computer was to computing. So I see it as an exciting opportunity.

Every field has challenges, but there are several very standard steps that can be used in creating products for that market:

- Go to where the action is. You can’t design a diagnostic tool or a treatment tool by sitting in your office. You’ve got to go to where those customers are. If you try to design things from an idea or from reading something, when you try to apply it you’ll find that it doesn’t work, because it requires electricity, or some stupidly simple thing like that.

- Talk to the people who have the problem and listen to what they have to say. Talk to 100 customers first – if you don’t do that, the chances of failing go up by a factor of 100.

- Find out everything there is to know about the context of the problem. There’s a context in a clinic in a 10,000-population town, there’s a context in a remote clinic in a smaller place, and there’s a context in a hospital in a city. So you have to understand all that.

And I want to mention that I’ve devoted the rest of my life to creating models for these new multi-national businesses serving $2-a-day customers. I’m incubating four companies, actually. And each company has the mission of transforming the lives of at least 100 million $2-a-day customers, earning an attractive profit, and generating annual sales of at least $10 billion.

JM: I understand those companies will involve water, energy, education and health.

PP: Yeah, I’ve put education and health on the back burner, since I’ve bitten off a bit more than I can chew with four. So I’m just going to wait until the right time.

JM: Can you talk more about your vision for the health care company?

PP: Yes. In India, in the rural villages where we’re working, the government clinic system is very often people’s least desirable option. The doctors get paid a pitiful amount, so they have to moonlight. They often, under the table, charge for writing prescriptions. The clinics are in market towns, so there aren’t health services available in the scattered rural areas where a disproportionate percentage of $2-a-day people live. So I want to introduce a decentralized village health system that has affordable medicines available for sale.

Perhaps it would be tied to the kirana shops [small-scale local stores] – that’s the last mile distribution issue. You’d have like a triage system, with paraprofessionals who are trained to do some of the first-line interventions, backed up by people like nurses, backed up by physicians. I would look at the business part of it, to make it profitable first, because that’s the path to scale. Then I’d build in those services which are most important for diagnosing and treating illness.

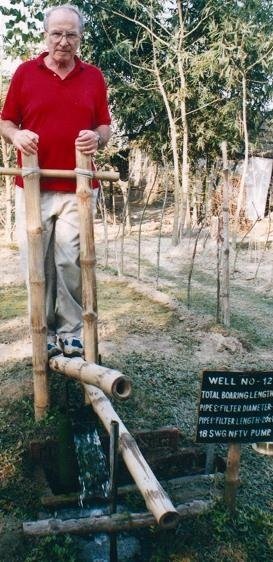

(Right: Paul Polak demonstrating the treadle pump he developed with International Development Enterprises.)

JM: That brings up another question: when you have a product that people’s health, and sometimes their life, depends upon, is there any moral ambiguity in focusing on profit first, rather than on philanthropic giving or government programs?

PP: No, not from my perspective. It’s a little bit of a misinterpretation to say that we focus on profit first. In all of these global businesses that I’m talking about, we incorporate a social mission into the overall mission of the organization. But the challenge is how to bring that impact to scale. My contention is that the current models that work at scale are global businesses – and the driver is profit. So if you can make something profitable that achieves a major social mission which is built into the mission of the organization, you’re accomplishing both.

I’m not saying that the market is the solution to everything. But I’m saying that with a social mission, making something work as a business is the best way of reaching scale. I also want to make it clear that I don’t think that market solutions are going to solve all the health problems in the world. There is a need for public investment. But I am saying that the marketplace solution has barely been tested, so we don’t know how far it can go, either in education or in health.

JM: But let’s say that some company comes up with a way to market an inexpensive medicine to poor communities, and they’re charging five cents a pill for it and making three cents profit. If they were to lower the price to four cents a pill, it would be even more accessible. Where is the line drawn?

PP: There are two ways of dealing with that. You can set up government regulations to limit the profit, which will be circumvented very quickly. Or you can encourage the forces of the marketplace to work, so that competition comes in and says, “Hey, these guys are making three cents profit. I could sell this for four cents and steal all their customers.”

Markets are uncontrollable, so they’re not a panacea. But I fully expect that if a company is profitable, it’ll bring in competition that brings the price down. There are all kinds of nasty things that businesses do to fight real competition in the market, so I’m not a naïve “capitalism solves everything” type of person. I just think that creating new markets to address social problems is probably better than the other remaining options.

- Categories

- Health Care