Smallholder Farmers and Big Business: 5 Insights from the Field

Modern agricultural practices and new technologies have transformed the productivity and lives of large farmers, but often fail to reach small and very small farmers for a variety of reasons. These include farmers’ lack of cash, unpredictability of personal circumstances or lack of cushion if harvests fail, to name a few.

However, some pioneer companies and organizations across the world have sustainably increased the income and livelihoods of millions of smallholder farmers, by sourcing produce from them or selling products to them.

What do these pioneers tell us? In a study rigorously comparing the performance of 15 successful companies and organizations worldwide, consulting firm Hystra (where the author is a partner) has drawn several counterintuitive insights. Here are a few key lessons from the report, “Smallholder Farmers and Business: 15 Pioneering Collaborations for Improved Productivity and Sustainability.”

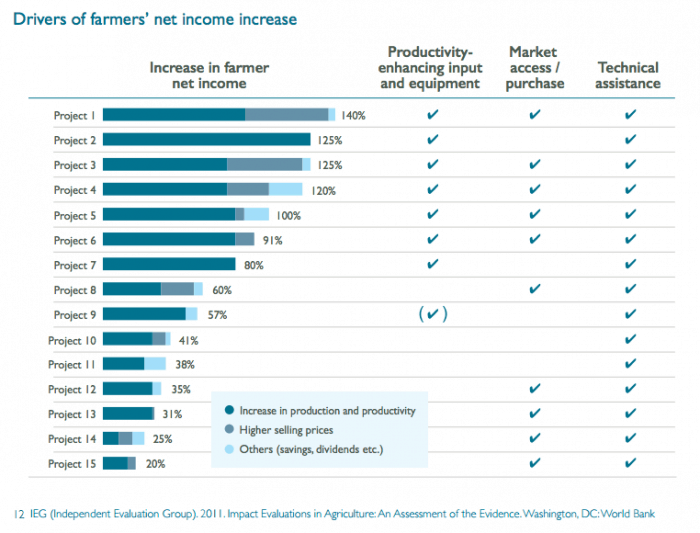

Technology drives productivity and impact, first and foremost

Farmers can increase their net yearly incomes by 80-140 percent when they have access to productivity-enhancing technologies such as improved seeds, micro-irrigation systems or improved cow breeds. In contrast, other interventions focused exclusively on “fixing” dysfunctional markets and redistributing value in the supply chain (e.g. replacing informal traders, improving market access or passing on a price premium) only brought 20-60 percent additional income to farmers.

The provision of technologies also puts farmers in the driving seat: It empowers and gives them the means to improve their productivity and income. In turn, larger and more successful farmers will be in a better position to negotiate better prices, access and contracts. Finally, as more value is created at the beginning of the value chain, there is more to share between all the players along it, creating a win-win situation for everyone.

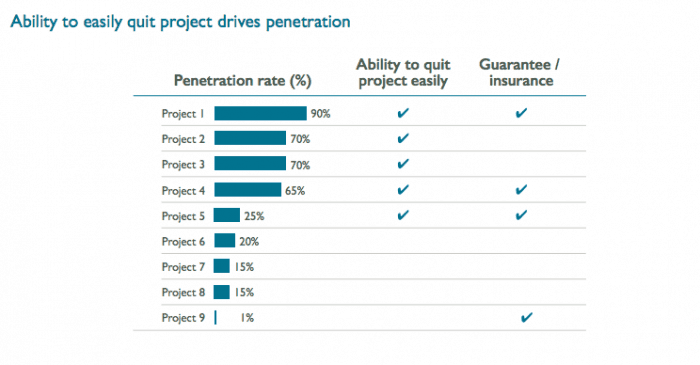

Farmers do not fear risk, they fear being locked in

Much has been written on smallholder farmers’ risk aversion when considering adopting new practices and technologies. However, when looking deeper into what drives farmers’ adoption rates of a new practice, technology or contractual engagement, we find it is not the size of investment required, the attractiveness of possible returns or the provision of insurance/guarantees that matter. Instead, it is the reversibility of their decision.

Organizations and companies that struggle to achieve widespread adoption offer “one-way tickets,” meaning it becomes very difficult for farmers to go back to the status quo if they change their mind (e.g. because their circumstances have changed, or the new line of cultivation is less successful than expected). In contrast, organizations that enjoy rapid and widespread adoption avoid engaging farmers in long-term commitments, leaving them able to go back to previous practices at little or no cost.

An example would be to offer farmers to switch from maize to soya for a season (or as long as soya brings higher prices) vs. proposing that farmers invest into cocoa seedlings, which take years to become productive.

We also see in the table above that insurance alone does not effectively address farmers’ concerns. It is not merely drought or disease they seek protection against. Rather, it is the “irreversibility” of proposed changes which drives farmers away from interventions that could improve their livelihoods.

Early adopters or the enlightened middle

When launching a new project, it seems intuitive to focus on enrolling the larger and more successful farmers first. They have more means and chances to succeed, while smaller farmers are more vulnerable to failure.

However, the ideal early adopters are those in the “enlightened middle” – farmers resilient enough to invest in new practices, crops and technologies, but not prosperous enough to be satisfied with the status quo. Ideally, these farmers already engage with the community (e.g. if they also are teachers), which makes them likely to share their success with others.

After the right early adopters are chosen, organizations should over-invest in their satisfaction and success through tailored and intensive support. For example, the BASF Samruddhi program sells quality inputs to soy farmers and supports them by providing intense in-person training for two full planting seasons.

Demonstration and word-of-mouth from satisfied early adopters is a powerful tool to enroll more farmers. Conversely, failures or dissatisfied farmers are sure to spread bad publicity that will slow expansion locally.

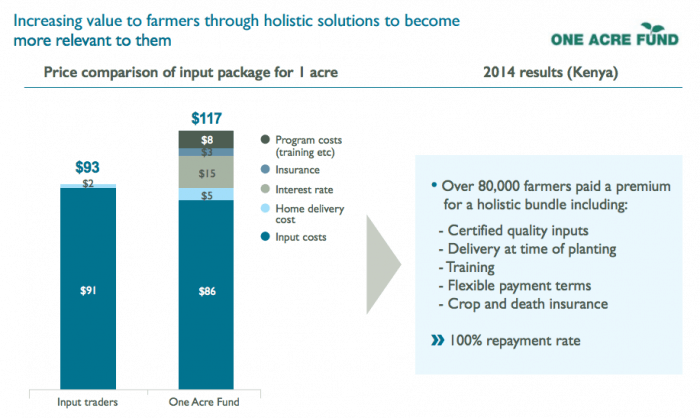

Integrating the value chain to increase farmers’ loyalty and unlock superior value

Offering a wider range of benefits to farmers gives organizations and companies a unique competitive advantage, making them more or less irreplaceable. By becoming essential to farmers’ success, organizations ensure that farmers choose to work with them repeatedly. This creates a virtuous circle whereby both farmers and organizations invest more year after year into one another’s success: smallholder farmers invest into more expensive, productivity-enhancing inputs and produce more crops to sell; this allows these organizations to earn enough margins to develop even more distinctive, holistic and varied suites of products and services.

One such example is JAIN, which started by selling micro-irrigation systems and expanded into complementary products and services. It now produces and sells improved seeds, purchases harvests from contracted farmers at guaranteed prices, processes crops through its own factories for export, uses biogas digesters to power the factories and converts waste into manure, which is then sold to farmers. This value chain integration has benefited both JAIN’s 200,000 farmers, many of whom have increased their annual income by $500-4,000, and JAIN, which has increased its revenue per farmer and at the same time decreased operating costs significantly. In 2014, it had $1 billion in turnover.

Another example is One Acre Fund, which proposes a comprehensive service bundle delivered to the farmer’s doorstep: improved inputs on credit, training to maximize productivity, crop and life insurance and market access. Moreover, inputs are delivered at the time of planting and farmers are offered flexible repayment terms. Farmers value the package and are willing to pay 25 percent more than what they paid to traditional input traders.

With this scheme, One Acre Fund has laid the foundation for a virtuous cycle whereby farmers increase their productivity and incomes and thus remain loyal to the organization, which can in turn offer them even more comprehensive services over time.

How to reach scale and impact? Farmer groups vs. intermediaries

While it is tempting to work through intermediaries such as cooperatives or well-established farmers’ representatives to quickly reach scale at a lower cost (one field officer can be in charge of 400 to 1,000 farmers), there are downsides, too. Organizations working through intermediaries often suffer from a lack of control and poor proximity. For example, the Kenyan social business Juhudi Kilimo initially partnered with cooperative banks to channel loans to farmers for productive assets. While this allowed them to offer cheaper credit, the co-ops were increasingly late paying back loans and Juhudi Kilimo lacked the direct relationship with farmers to counter this. Juhudi Kilimo had to discontinue the scheme and manage loans directly.

To avoid these problems, organizations often work directly with groups of 15-30 farmers who come together to use services or products that are offered. Compared to working directly with individual farmers, this allows for relatively faster expansion.

Juhudi Kilimo now helps farmers form small groups, making peer learning easier. In addition, each member’s loan is guaranteed by the savings of the other members, reducing default rates to only 3 percent. ECA – an agriculture company sourcing maize from very small Mozambican farmers – often finds farmers’ groups already formed when they move into a new area because their reputation travelled faster than their teams. This results in comparatively low outreach and training costs because each extension officer can cover 100 to 500 farmers. Khyati Foods in India started enrolling farmers into organic certification through intermediaries, but could not reach the level of loyalty required to complete the three-year conversion process. After switching to a more hands-on approach with groups of 30 farmers, it now retains 100 percent of the farmers.

Interested? More information on these questions, as well as many more insights on creating more wealth along the value chain, running cost-efficient operations and sharing value back with farmers sustainably, can be found on Hystra’s newly released report “Smallholder Farmers and Business.”

This report was prepared with the support of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, Danone Ecosystem Fund, responsAbility Investments AG and C&A Foundation.

Top image: A sales representative from Juhudi Kilimo shows customers various energy saving products. Image credit: Juhudi Kilimo’s Facebook page.

Jessica Graf is a partner at Hystra, where she leads the work on agriculture, health, safe water and sanitation and innovative distribution models.

- Categories

- Agriculture, Impact Assessment