A New Mission for an Old Model: Unlocking Sustainable Water Through Savings Groups

To reach the Sustainable Development Goals of universal access to clean water and sanitation by 2030, the World Bank estimates we will need to quadruple spending to $150 billion per year. Given this financing gap, every investment in clean water counts.

Yet an estimated one out of three rural water points are broken across Sub-Saharan Africa, and third-party research in Uganda, our base of operations at The Water Trust, found 45% of borehole wells to be non-functional, with just 18% meeting basic standards of quantity, quality and reliability.

The Challenges of Community Management of Water Resources

Historically, the water sector has trained local community members to form a management committee that volunteers to collect user fees from their neighbors, manage these funds, and contract local mechanics to undertake repairs to water point pipes, pumps and other equipment. This community-led approach has been generally unsuccessful, with some stating that community management itself is the problem. It is certainly the case that, as a result of the volunteer management model, water points that might have cost $5,000 to $10,000 have fallen into disrepair and become abandoned after a $50 repair goes unmade due to a lack of funds or poor management.

Some in the sector have responded to this challenge by directly subsidizing maintenance of rural water points (i.e., acting as a quasi-utility). Others have responded by strengthening the capacity of the local government or local handpump mechanics to improve the supply of maintenance services provided to communities. NGO-subsidized maintenance services address a real need, but there is no existing financing model for scaling up these services. Meanwhile, many local governments are too inadequately funded to even maintain water and sanitation at health centers and schools. While increasing funding of local services is critical, in many countries publicly-financed maintenance will not reach rural communities in the near future.

However, there is reason for hope. The rumors of the death of community management are greatly exaggerated. While volunteer management committees have failed to reliably mobilize and manage funds for water point maintenance, savings groups have a long history of mobilizing significant sums of money — $1,000 to $2,000 per year — in these very same communities. These groups have not only successfully extended savings and credit services to the unbanked, they have also created highly-functioning, self-sustaining community-based institutions that can raise and spend $100 or more for social purposes, such as funeral allowances when a relative of a group member dies.

Applying the Savings Group Methodology to Water Access

Formal savings group methodologies like Village Savings and Loan Associations have decades of success, achieving high group membership, meeting attendance, financial performance and sustainability. These groups have tried and true methods for addressing many of the challenges that plague volunteer water point management committees, such as regular weekly meetings where payments are made, highly-transparent financial management practices built for low-literacy populations, and a profit incentive for community members to follow the agreed-upon group rules, including user fee contributions.

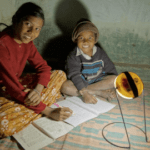

In 2016, The Water Trust trained our staff in the Village Savings and Loan Association model, adapting its methodology to enable saving for the shared community water points. We introduced the program to 20 communities, and 18 signed on. Today, we have trained more than 200 savings groups (which we now call “self-help groups,” given the groups’ objectives) with another 400 to be trained by the end of this calendar year. With each group comprising about 30 members and managing a water point benefitting 250 people, we are scaling from 50,000 to 150,000 people across Masindi and Kiryandongo districts in western Uganda.

We have scaled up our efforts after seeing firsthand the transformative effect a savings group can have on the financial and organizational capacity of rural communities, and how this capacity can translate to increased water point maintenance and high water point functionality.

Our recent evaluation brief highlights several key results across a sample of 192 groups monitored from 2016-2019:

- Groups have 95% water point functionality (in contrast to 55% of typical boreholes in rural Uganda) and 97% self-help group functionality

- In an average year, groups accumulate $1,386 in total assets, spend $32 on water point maintenance, and maintain a reserve fund of $71 to pay for future repairs (spending and reserves exceed the $80 annual target for waterpoint upkeep.)

- Membership, savings, the water point reserve fund and water point maintenance spending all increase over time, suggesting increased engagement rather than attrition.

“It was just that one thing, us not knowing where the money used to go that made me refuse to keep paying into the group, but now I can see some good in it,” says Mary Joyce Akurutu, a savings group member in Kiryandongo district. “Right now we know for sure that the money we collect benefits us. Even when I have given 6,000 UGX (~$2), I know when I come crying for help in case I have a sick person, I will be given a loan. That is the reason why now we’re very OK within the savings group.”

Why the Savings Group Model is Effective

Inadequate savings and access to capital more broadly is not a problem specific to rural water access. In Mary’s explanation, we hear the importance of transparent management and the access to savings and credit for personal risks. When a volunteer management committee asks a household for a contribution to build a reserve for future repairs, they are asking for a contribution to a communal water point insurance fund when that household has little to no savings or insurance for its own risks, such as medical emergencies or funerals. Likewise, the volunteer committee members who collect the funds are asked to create a separate mental account for the water point savings that they are not supposed to access for their emergencies, school fees and other necessities. This is not a reasonable expectation.

Savings groups have proven methods to address the problems of opaque accounting and unpaid, cumbersome fee collection. Weekly meetings provide visual and verbal accounting of funds, and water fee collection is integrated into the regular meeting process of making savings deposits and contributions to the group’s social fund (which is used to compensate members when they lose a loved one.) The “water bag” physically separates the funds for the water point and enjoys the same security as the group’s personal savings — a physical lock box with three locks, or three pin numbers if they connect to local mobile banking options. More information on the mechanics of group operations can be found in our field training manual.

Perhaps most importantly, savings groups introduce an incentive for community members to abide by agreed-upon rules for water point contributions (among other group rules they establish in their constitutions.) Most group members’ households lack access to formal savings and credit, and the opportunity to save for a large annual dividend while enjoying loans throughout the year is highly valued. For example, in a number of cases we have seen people who do not even use the water point ask to participate, and agree to pay the water usage fee for the privilege.

Beyond a robust financial institution for water point maintenance, savings groups offer additional promise to the water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) sector. The group meetings provide a regular, weekly platform for behavior change messaging. We are currently piloting a program that aims to improve the poultry management of group members, with the groups acting as a local community of practice and a source of capital for improvements.

The Impact of COVID-19 on Self-Help Groups

The COVID-19 pandemic has certainly interrupted regular weekly meetings and reduced attendance for many groups during this time. At the same time, communities with self-help groups enter this crisis with the advantage of accumulated savings — both individually and collectively — and a dynamic community-level institution to help them navigate this difficult moment. While the impact of COVID-19 and the associated economic crisis on groups is not yet clear, we have seen no decrease in interest from community members to form new groups. While new group formation must be done in accordance with government guidance and with additional risk-reducing precautions, COVID-19 has only increased the need for the financial and social capital that self-help groups provide.

With tens of millions of people across the world participating in formal savings groups, the replicability and scalability of a savings group approach is proven. With hundreds of millions of people dependent on poorly maintained rural wells and an immense financing gap in the WASH sector, the utility of a community-led solution is clear.

Looking forward, we see great scope to advance financial inclusion and access to clean water through greater collaboration across the WASH and financial empowerment sectors. In the year ahead, we plan to launch a randomized controlled trial of this program, to produce a more robust evidence base. We will also seek out partnerships with organizations interested in adapting and implementing this model in similar rural contexts.

Note: The development of the savings group for sustainable water model was made possible through the support of Deerfield Foundation.

Chris Prottas is Executive Director of The Water Trust.

Photos courtesy of The Water Trust.