To Change the World, Change Your Economics: How Degrowth Can Shrink Overconsumption in the Global North While Allowing the Global South to Grow

It isn’t fair to lay the blame for all the world’s problems at the feet of any one cause, or any one “ism.” But we can attribute a lot of the problems we face today, from inequality to environmental degradation, to our flawed economic system.

The global economy largely operates under an economic structure that has come to be known as neoclassical economics. Classical economics emerged in the late 18th century through the writings of Adam Smith, David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill and others, who based their thinking on the belief that individuals acted rationally to maximize their self-interests. Classical economics emphasized the efficiency of free markets, and the role of supply and demand in determining prices and resource allocation.

Neoclassical economics began to develop in the late 19th century, building on classical economics by introducing concepts such as “marginal utility,” mathematical modeling and the role of government intervention in the economy. It became the dominant economic system in the aftermath of World War II when the Allies, after winning the war, made the economic rules that would govern the global economy going forward. As a result, a reliance on markets to solve problems, skepticism about government intervention, deference to the private sector and a focus on constant growth have become the accepted norms of our economic system — though the “flavors” of neoclassical economics practiced around the globe vary due to legal, cultural and policy differences across countries.

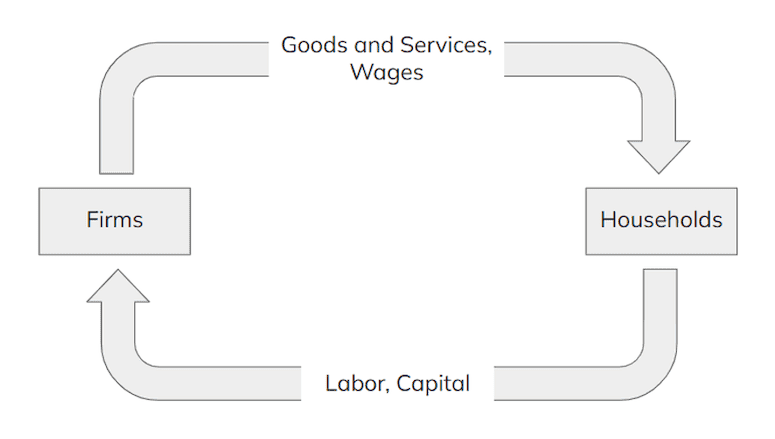

The standard conception of neoclassical economics is based on firms and households virtuously working in harmony to produce the products and services that society needs, as illustrated by the graphic below.

However, neoclassical economics has a fatal flaw: one that only became apparent as the environmental impacts of our vast global economy became clearer. It does not adequately deal with the facts that our economy depends on limited natural resources and massive amounts of energy as inputs to the system, and has no satisfactory way to deal with the waste produced by our economic activity. It operates on a planet with finite resources, and finite places to put our waste, but assumes that growth can go on forever. It does not take a PhD in economics to understand that in the long term, that math breaks down.

As our current economic system lacks the ability to solve the global problems of inequality and environmental collapse, it’s clear that the world needs a new form of economics, one that adequately considers the resource limitations we’re facing, and the resultant limits on growth. But what might an alternative economic system look like, and what does this conclusion mean for development finance — and for countries in the Global North and South? We’ll explore these questions below.

(For the sake of this discussion, we are defining the “Global North” as developed countries, and the “Global South” as developing countries. This is a general rule, but there can be gray areas. For example, China has, for most of the past century, been considered a developing country and part of the Global South. But its growing economic and political power would now put it more in the “Global North” category, in the minds of many.)

The Emergence of ‘Ecological Economics’

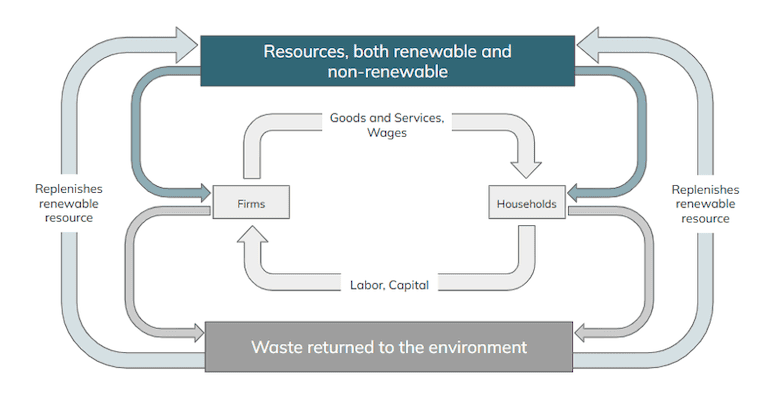

While its roots are old, ecological economics is an emerging concept which adequately considers both the energy needed for our economic activity and the waste produced by that activity, as illustrated in the graphic below.

With its grounding in physics, it acknowledges that our economy sits within nature, placing real physical limits on the economic activity of humanity. This can be understood through the concept of an “empty world” vs. a “full world.”

For most of human history, mankind operated in a relatively “empty” world, which meant that human activity did not have a large impact on the planet. If a population used up the resources in one area, it could move to a new area, allowing the resources of that first area (water, wildlife, fruits, vegetables and timber) to regenerate. But we now live in a “full” world, where our economic activity and resource use are outpacing the planet’s capacity to regenerate.

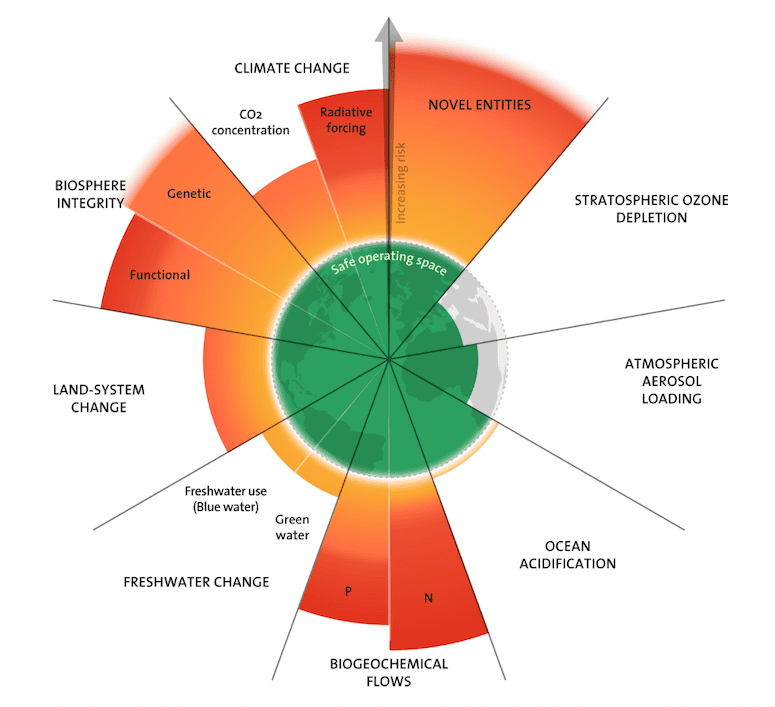

We know we are in a full world because we have pushed past seven of the nine planetary boundaries that scientists have established as the “safe operating space” for humanity, as shown in the graphic below.

The fact that we have exceeded these boundaries in areas like climate change, land use, water use and more means that these systems are breaking down, and are at the point where they can no longer support us over the long term. If we don’t get back into the safe operating space, these systems will no longer be able to serve as the “life support system” of humanity.

Yet due to the failure of our economics, we continue to vastly misallocate resources on the planet. Under neoclassical economics, the world’s economic, political and cultural goals are all organized in service to economic growth — even though enabling this growth uses too much energy and materials, and the system does not adequately deal with the waste products created by that economic activity.

Shifting the Growth Paradigm on its Axis through ‘Degrowth’

The environmental degradation of the planet has been driven mainly by the Global North (including countries like China that have risen through the income ranks), using the resources of the Global South — both historically through colonization, and in modern times through a financial system that keeps emerging economies dependent on the export of their natural resources to wealthier countries.

As a result, in order to move humanity back into the “safe zone” of the planetary boundaries, the Global North will need to cut back on its consumption of energy and materials — without imposing undue restrictions on the development of the Global South.

This is where “degrowth” comes in. Degrowth refers to an equitable downscaling of production and consumption so the world can remain within planetary boundaries — a downscaling that will need to come primarily from the Global North.

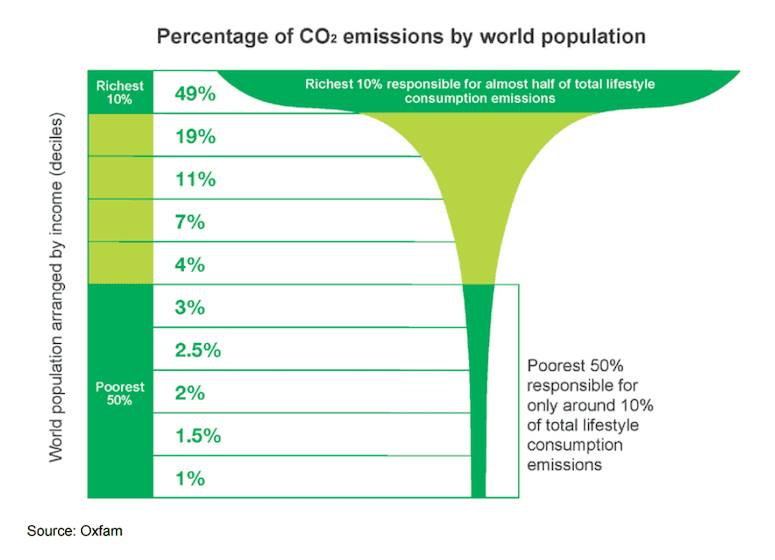

The Global South should be allowed to grow. The main problem with humanity living beyond its means comes primarily from those of us living in wealthier countries. For instance, the richest 10% in the world are responsible for about half of the world’s carbon emissions, while the poorest 50% are responsible for only about 10% of emissions, according to Oxfam (see the graphic below).

For that reason, we shouldn’t be looking to stifle growth in the Global South. Instead, we should be supporting the growth of economic activity in the Global South, and questioning whether the growth we have in the Global North is what we need.

Of course, some countries in the Global South also have high energy consumption and emissions, but most do not. For example, India has lower per capita emissions than nearly all developed markets, but it is nevertheless the third highest global emitter of CO2, and it still relies on coal, a top driver of carbon emissions, for about 74% of its electricity. So though curbing emissions from the Global North should be the first priority for action, growing economies like India and China, due to the sheer size of their markets and emissions, will need to address their resource usage more urgently than other markets in the Global South.

There is, of course, no international authority or existing treaty to rein in harmful growth. A move from a growth economy to a post-growth economy won’t come about because some president or parliament decrees it, but because a society realizes that such an economic model is more desirable in the long term. That will require a significant cultural change, and a change to the core beliefs of many of us who have only known a world in which never-ending economic growth was taken for granted as an unmitigated good.

In the long run, we need most regions of the world to reach a sort of “development equilibrium,” so that resource exploitation at the expense of the Global South will cease, and the global community will return to operating within planetary boundaries. For the Global North, this would mean shifting economic activity to those sectors that do not push us past planetary boundaries. This would likely involve the shrinking of industries such as fossil fuels, mining, air travel, mass agriculture, fishing, timber and others that have substantial negative environmental impacts. For example, the Global North’s agriculture system would need to reduce the production of beef and dairy cattle, which have adverse effects on forestry, water use, climate change and biochemical flows. We would still have beef and dairy production, just at lower levels. Industries that do not push us further past planetary boundaries would expand, such as education, local food production, healthcare and others. Emerging industries such as AI, which use vast amounts of energy, would need to either scale back their ambitions or operate with less energy consumption.

If a post-growth economy were imposed as some kind of permanent austerity, it would surely fail. However, if over time, we as a society choose to live in a post-growth world because we see it as necessary for our survival, it can succeed. That would require a large cultural change that would take time, but it’s not an impossibility. Cultures are always changing, and if awareness of the dire impacts of our current trajectory grows, we can collectively move our global culture away from overproduction and overconsumption over time.

What Needs to Happen for a Degrowth Agenda to Emerge

When we think about what is at stake in the global climate and environmental crisis, we tend to think of money or jobs lost due to climate change or environmental degradation. We have been led to believe that we should be able to overcome these short-term setbacks and continue with business as usual. But this is starting to change, as this mindset is increasingly being challenged by floods, fires and other extreme environmental events that are too big to ignore.

Nevertheless, countries in the Global North are largely able to handle these events and rebuild their communities, as happened after the wildfires in Los Angeles and the floods in Texas earlier this year. While the costs are huge, these countries’ leaders have decided to pay them when they arise, instead of insisting that their constituents start changing how they live. While cracks are forming (for instance, it is increasingly hard to insure your home in parts of Florida or California), these countries are continuing with their usual economic activities — and in some cases, even loosening environmental rules.

But it is a different story in the Global South. In these countries, governments and resources are already stretched thin — and now they face new cuts in international development aid. They do not have the resources to rebuild after each disaster: Their industrial infrastructure is much more fragile, and their climate-related disruptions are more severe and frequent.

In these countries, climate change will continue to generate unbearable heatwaves, failed crops and depleted water supplies. “Building back better” is often not a realistic option for them, so climate shocks often result in a lack of food and security that leads to mass migration. The defunding of programs such as USAID will likely have the unintended consequence of more migration from countries that will become progressively more food and resource insecure as climate change and other environmental damages grow in intensity year after year.

As the reality of this situation begins to be translated into policies, the ecological footprint of the Global North will be forced to decrease. The famous Herbert Stein quote, “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop,” helps us to see that at some point, the overconsumption of resources in the Global North will be addressed. This will likely come to pass because of a combination of disasters or a consistent degradation in the quality of life that may include hundreds of different causes, from heat waves and hurricanes, to flooding, massive crop failures — and the mass migration these events inevitably cause. While the manner in which this will be achieved is outside the scope of this article, there will come a point where climate, biodiversity loss, deforestation, water use or the breaching of other planetary boundaries will lead to consequences that demand action. This could result in an economy that follows a post-growth path, with decreases in resource use driven by a new focus on wellbeing instead of GDP growth.

Investing, in its essence, is a practice of measuring and reacting to risk. Up to this point, the financial markets and global investment decision makers have done a poor job of evaluating the true risks of climate change and environmental degradation. They vastly underestimate the risk of financial assets breaking down due to the destruction of our environmental systems. But at some point, the true risks of continuing down our current path will more accurately be factored into asset prices.

This will likely not happen all at once, but it will ultimately lead to a shock in the investment system: When investors realize that mitigating the worst-case scenarios of climate and ecological collapse will result in a great deal of stranded assets in the Global North, this will significantly affect the flow of products, resources and capital between the Global North and Global South. Global North-based capital, primarily in the form of credit, has financed extractive and resource-intensive sectors across the Global South, which have, in turn, sold these raw materials back to Northern businesses and consumers. These commodities are contributing to the imbalance between overconsumption in the North and underdevelopment in the South. In spite of the contributions of development and impact finance, there is little reason to think that this dynamic will change as long as the underlying system is based in neoclassical economics.

However, if exports of material resources from the South decrease as a degrowth agenda leads to reduced demand from the North, this will lower export revenues and give the South an incentive to reorient its economies to domestic consumption and wellbeing. Meeting the wellbeing needs of its citizens will require growth, and without the resource demands of the markets of the Global North, the Global South will be more free to plot its own course. These countries’ resources could be used instead to create a thriving middle class — though this will require new leadership, new ideas and new capital.

Managing the Impact of a Degrowth Agenda on the Global North

This raises some key questions: What will happen to jobs and wellbeing in the Global North if the economy isn’t growing? Will this mean a lower standard of living in these countries?

These are legitimate questions, and ones that are already being addressed by several policies that are often associated with degrowth — but are not exclusive to degrowth thought. This is not an exhaustive list, but the examples below highlight some policies that would be part of a transition to a post-growth world.

A four-day workweek: In recent years, several countries have experimented successfully with a four-day workweek, including Iceland, Belgium and the U.K., as have companies such as Unilever and Microsoft. A four-day workweek gives workers more time, and it is also good for the environment. If we work less, we do not travel as much, and we tend to make less resource-intensive consumer choices.

A just transition: It’s important to recognize that many individuals are currently employed in unsustainable sectors, and we should not just leave them behind as the economy changes. A just transition focuses on helping these individuals pivot to working on greener technologies or in other fields. In Canada, for example, legislation passed in 2024 aims to help workers transition away from fossil fuel work to green energy employment.

Universal Basic Income (UBI): Pilot programs have been run in Finland, the U.K., the U.S., Kenya and a number of other locations, showing positive impacts of UBI on physical and mental health, full-time employment rates and other areas. UBI could be a key part of accomplishing the just transition mentioned above, by making people less dependent on their paid jobs for survival.

Universal Basic Services: Our current economic system depends largely on the artificial scarcity of things that are essential for our lives. Healthcare is a good example, and education, housing, food, energy, public transport and access to the internet are some others. Some consider the free provision of these services — a concept known as Universal Basic Services — to be a more egalitarian alternative to UBI. A society that provides these services would see a direct effect on wellbeing outcomes, and a decrease in people’s need to work more just to buy the basics of life.

Public job guarantees: If growth slows down, millions of people will lose their jobs, and that is why we cannot walk away from capitalism as we know it, right? Perhaps not. Over one dozen countries have implemented some form of a job guarantee program, including the United States, Argentina, France, South Africa and India. Job guarantees can help ensure a baseline quality of life, enabling policies like the four-day workweek.

Understanding the Impact of a Degrowth Agenda on Global Capital Flows

If (or when) the Global North enters its degrowth phase, there will be excess liquidity in the Northern investment sector. This will occur as Northern capital-intensive industries such as fossil fuels, mining and industrial agriculture are slowly downsized in a post-growth world. This lack of demand for capital will lead to a shrinking of the financial sector itself, while also freeing up vast amounts of capital in the system which will need to be invested.

The adoption of degrowth policies by the Global North will provide the Global South (and investors) with an opportunity which may not be obvious at first. As mentioned above, with the North completely reorienting and decarbonizing its economy, the Global South will need to reorient its own economy away from exporting resources, whose markets will be much smaller, and instead build the industries needed to meet the needs of its own citizens. This shift to local development and consumption and away from exporting resources could be supported by capital in the North, which under a degrowth agenda will be sitting idle with future institutional investors.

These future investors will need to totally reimagine the entire investment process, from credit agencies, due diligence processes, risk models and accounting systems to the final terms, conditions and pricing of the credit. These institutions may even need to move to more innovative structures such as recoverable grants, blended finance and zero interest loans, because there will be many fewer places to invest.

Many of these innovations have already been created within the impact investment community or implemented by institutions in the Global South — such as the case of the African Union launching its own credit agency. But capital has remained stubbornly scarce in the Global South, as institutional portfolios — along with most sustainable and impact investments — continue to be allocated mostly to the North. Blended finance is still not standard practice, and social entrepreneurs still struggle to find funding. All of these issues are driven by the fact that investors do not see any reason to change their current practices.

But once degrowth becomes necessary, this dynamic could shift, and capital could find its way to the hundreds of ideas and innovations that could help the North live within planetary boundaries, and the South better meet the needs of its citizens through fairer terms of trade and investment. Once people see this connection, a post-growth future could be built by a huge coalition of people both in the North and South who believe in creating a more sustainable and just future.

While to many, these developments may currently seem impossible, that may be because they are still looking through the lens of neoclassical economics, and trusting in the resulting policies (i.e., “the market will solve everything”) to prevent collapse. However, neoclassical economics does not adequately address the physical limits of our natural world — and it shows no sign of changing. Once we take these limits into consideration, we realize that we must change our economic thinking. This shift in thinking will not happen overnight, but it will happen: Indeed it must, due to the physical limits to endless growth.

It is only a matter of time until markets and investors begin to recognize this reality.

Matt Orsagh and Steve Rocco are co-founders of the Arketa Institute for Post-Growth Finance.

Photo credit: robert6666

Sorry. This form is no longer available.

- Categories

- Energy, Environment