The World is Losing the Fight Against Malaria: Could Drones and AI Help Defeat the Disease Once and For All?

The fight against malaria has, at least until recently, been one of the great 21st century success stories in the global healthcare space.

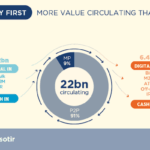

Since the turn of the millennium, increased funding of anti-malarial efforts, as well as a firm political commitment to defeating the disease, have had life changing results. The Gates Foundation estimates that 2.2 billion malaria cases have been prevented since 2000, saving 12.7 million lives.

However, this progress has stalled. In the two years after the COVID-19 pandemic, the proportion of global research and development funding dedicated to malaria fell by $103 million — from $707 million in 2019 to $604 million in 2022. Overall, global funding for malaria prevention efforts amounted to just $4 billion in 2023 — less than half the $8.3 billion target set by the World Health Organization (WHO).

A Global Loss of Momentum in Anti-Malaria Efforts

This drop in funding comes at a time when malaria cases are on the rise. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of cases rose to 249 million in 2022 — the highest number in nearly two decades. Since the pandemic we have seen uneven progress: While the global malaria mortality rate has dropped from 14.9 deaths per 100,000 in 2022 to 13.7 in 2023, cases have remained stubbornly high. In 2023, there were an estimated 263 million cases of the disease and almost 600,000 deaths from malaria, around 95% of which occurred in sub-Saharan Africa. More recent numbers are not yet available, however it is likely that these numbers have increased. In the absence of urgent intervention, experts warn that malaria cases could “skyrocket” in 2025.

One of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is to reduce malaria case incidences and mortality rates by at least 90% by 2030 — targets which are currently off track by 55% and 53% respectively. The African Union’s aim of eradicating the disease by 2030 is, sadly, similarly behind schedule.

There are worrying signs that the situation could get worse, as public and development sector funding sources are drying up. Substantial budget cuts at agencies like USAID, one of the largest funders of global malaria programmes, are threatening to undo decades of hard-earned progress — for instance, by stifling funding for mosquito nets in Africa and elsewhere. In Zimbabwe, for example, funding pressures in the first four months of 2025 contributed to a 180% increase in malaria cases, and a staggering 218% increase in the number of malaria-related deaths, compared to the same period in 2024.

These trends, which have emerged in many African countries, are also being driven by longer-term factors such as climate change, as longer and more frequent rains are creating more breeding sites for mosquitoes. In turn, this is increasing mosquito populations and the rates of malaria transmission.

To add further pressures, there is also the growing issue of antimalarial drug resistance, which has already been confirmed in Eritrea, Rwanda, Uganda and Tanzania and is suspected in Ethiopia, Namibia, Sudan and Zambia. According to the WHO, these increases in drug resistance have been driven by factors that include the use of substandard medicines, as well as treatments not being followed to completion.

In response to these growing challenges, many African countries are now scrambling to maintain even basic prevention efforts, such as distributing mosquito nets or ensuring widespread access to effective medication. We have therefore come to a critical juncture: Will the global community double down on defeating malaria, or will we allow cases to continue rising and claim even more lives?

A Drone-Based Solution That Can Help Defeat Malaria

With public health systems under increasing pressure, the private sector has a unique opportunity, and responsibility, to step up. At SORA Technology, where I serve as the founder and CEO, we are working to implement innovative, tech-driven solutions that can help defeat malaria as cheaply and effectively as possible.

Most public health efforts currently focus on using physical equipment such as mosquito nets and indoor spraying to reduce rates of infection. While important, these methods are increasingly proving insufficient, especially as more malaria infections now result from outdoor bites that nets cannot prevent.

By contrast, SORA uses drone-based vector control to target mosquito breeding sites, to eradicate the disease at its source. SORA’s drones, which are equipped with AI-powered cameras, fly into remote areas that health personnel often have difficulty reaching in a timely manner. The drones are then able to assess the risk of water sources being home to mosquito larvae, based on factors such as water stagnation, vegetation density and topography. When a high-risk water source is identified, the drone then sprays a precisely calculated amount of insecticide to eliminate larvae before they become adult mosquitoes that can spread malaria. This process also takes into account relevant environmental factors, ensuring that pesticide is applied in a safe and effective way and does not contaminate local water supplies.

This approach, known as larval source management, has traditionally required a large amount of human labour and a huge amount of wasted insecticide. Government teams have often “blanket sprayed” entire areas without precision, with human workers going to homes and other locations to spray pools of stagnant water. This has led to waste, high costs and environmental concerns. However, by leveraging more sophisticated technology that uses insecticide in a targeted way, the amount of insecticide sprayed can be reduced by approximately 70%, with labor costs cut by around half. These savings are critical for countries working with limited health budgets, allowing malaria prevention efforts to reach a far greater geographic scale.

Furthermore, this approach also helps limit the environmental impact of insecticide. By avoiding overuse of insecticide, we can protect biodiversity and minimize collateral damage to ecosystems — a growing concern in malaria-endemic regions.

Putting Market-Based Solutions at the Forefront of the Fight Against Malaria

More widely, private companies like SORA are working with African governments to build market-based solutions, helping countries impacted by malaria to develop more resilient healthcare systems that aren’t dependent on the kindness of strangers.

Despite the recent struggles in the global fight against malaria, it’s important not to be pessimistic or defeatist. But reversing the current trend of rising malaria cases will require a rethink of how we fight this disease, and an openness to new, tech-driven approaches.

It’s also time to move beyond the idea that malaria is solely a problem for governments and NGOs — or indeed a strictly health-related issue. In fact, defeating the disease is one of the most overlooked economic levers available to African nations today. The World Economic Forum estimates that eliminating malaria could boost Africa’s GDP by up to $16 billion annually. That’s because malaria saps productivity, increases healthcare costs and disproportionately affects the working-age population.

Investing in anti-malaria efforts means investing in growth and economic development. Defeating the disease is in everyone’s best interests, including the private sector.

At SORA, we believe that with the right technology, we can prevent malaria from being a recurring crisis. But we need new actors, new tools — and renewed urgency to build a future where malaria no longer threatens Africa’s development.

Yosuke Kaneko is the CEO and Founder of SORA Technology.

Photo credit: frank600

- Categories

- Health Care, Technology