Mobile Money Providers Score a Major Win – But Are They at Risk of Losing it All?

The GSMA’s recently launched 2019 State of the Industry Report on Mobile Money highlighted a major milestone that the industry crossed last year: more than 1 billion mobile money accounts.

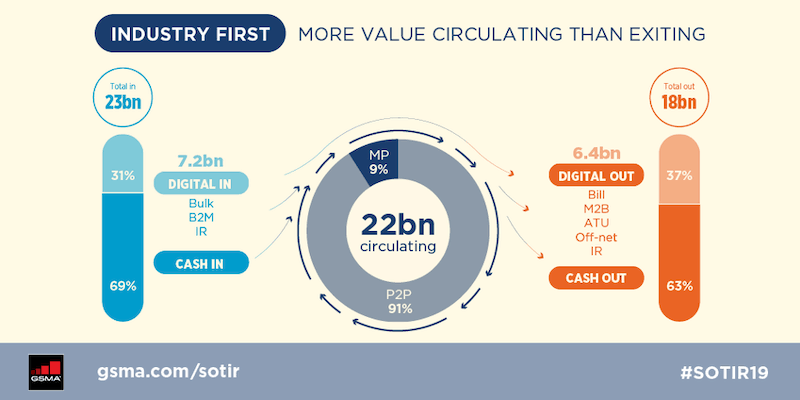

For the first time, digital transactions represent the majority (57%) of mobile money transaction values. A larger proportion of money is entering and leaving the system in digital form, rather than through cash. This means that customers are keeping their funds digital and actively using mobile money, rather than immediately converting that digital value to cash. And in another industry first—the total value in circulation (including person-to-person and merchant payments) reached $22 billion in December 2019, more than doubling over the last two years and outpacing the total value of outgoing transactions ($17.5 billion). User activity rates are at their highest level too – 35.8% in 2019 vs. 34.5% in 2018. And with COVID-19, all these metrics are set to accelerate as people move away from using cash.

These are huge achievements for financial inclusion, but it didn’t happen easily. Over the last 13 years, mobile money providers (MMPs) have tirelessly worked to establish agent networks, onboard customers and build a digital financial ecosystem. Their work has dramatically shifted the payments landscape for billions of customers worldwide.

New Digital Payments Challengers Emerge

However, the industry won’t have time to rest on its laurels, as the competitive payments landscape is rapidly changing, with over-the-top (OTT) players now operating in many markets. Over-the-top players use the internet, particularly smartphones, to provide a service—for instance, WhatsApp, Netflix and OPay, to name a few. The majority of MMPs, on the other hand, are mobile network operator (MNO)-led, which means they use a proprietary channel, like the SIM card or USSD, to provide their services, instead of the internet.

With the arrival of new OTT payments competitors, MMPs have gone from being disruptors to incumbents. In 2020, one noteworthy battleground that’s likely to emerge is Nigeria. Though the OTT threat has been there for a while, it’s about to heat up. With major recent investments flowing into these new payments players in the country, any provider focusing on profitability instead of market share will be crushed. Investors in OTT players are taking at least a 10-year view on the market, and are essentially going in for a land grab, claiming as much market share as possible without worrying about their businesses making a profit in the next decade.

That’s not to say they’ll have an easy ride. A few years ago, the OTT payment provider WeChat Pay came and went in South Africa, and a few other attempts by other OTT players have also proven futile. Setting up a mobile money service has always been hard, and that hasn’t changed. Yet increased penetration and usage of smartphones continues to present opportunities to new entrants. Keep an eye on PalmPay as it moves into Nigeria: It’s headed by Greg Reeves, an industry veteran who knows a thing or two about setting up mobile money services (Reeves led Vodafone’s group strategy in 2009, and over three years turned around various struggling deployments, particularly M-Pesa in Tanzania).

Though it’ll play out differently in each market, the threat to MMPs in Africa is finally here. It’s not from banks, nor from American or Chinese tech giants (at least not yet), as both have focused more on Asia: American tech giants like Google Pay, Amazon Pay and PhonePe (Walmart) are fighting for market share in India as direct participants, while Chinese giants (Ant and Tencent) have made investments in Indian firms like Paytm, and have also invested in leading MMPs in Pakistan, Bangladesh and other Southeast Asian markets. Instead, the threat in Africa is coming from other Chinese actors—players such as Meituan-Dianping, a group buying website for locally-found food delivery services, consumer products and retail services—who are willing to invest not only in technology, but in human resources on the ground.

Can the Mobile Money Providers Fight Back?

What’s more, other threats are growing on the horizon. In 2012, there were two mobile money accounts for every Facebook account in Africa. That ratio has now inverted, as Facebook seems poised to enter the payments market on the continent. How did this happen?

One reason is that mobile network operators (MNOs), many of whom run the leading mobile money deployments, don’t trust each other—every time they shake hands, they count their fingers to make sure none are missing. But back in 2014 they shook hands with Facebook, only to find that their entire arm was missing. That was the year when Facebook got MNOs to provide, free from data charges, a text-only version of Facebook called Facebook Zero, at a time when Facebook wasn’t well-known in Africa (whereas MNOs had built very strong brands). They hoped to use it to drive smartphone and data adoption, to the benefit of their own businesses. But instead, Facebook Zero (in addition to Free Basics) was the Trojan Horse that allowed Facebook to use MNOs’ networks to build its brand for free. For many people in Africa, Facebook is the internet – and it could likely leverage that user trust as a springboard to a successful payments platform.

Meanwhile, current trends make it inevitable that payment fees will fall to zero—we’re already seeing this in India and Southeast Asian markets, and Facebook’s cryptocurrency consortium, Libra, is working towards a similar goal on a global scale. This is also the modus-operandi of OTT players, who aim to move the business away from a pay-per-click/transaction model. When this happens, it’s going to be very hard for MMPs to stay in the game. It will be like the death of SMS texting after the rise of free instant messaging services – but unlike with instant messaging, mobile money comes with real costs. Getting funds in and out of the system is expensive – especially cash, which requires a network of physical agents. And it will take very deep pockets to subsidise these costs for any meaningful period, as customers become accustomed to purely digital, agent-less transactions.

To that end, these new OTT payments players will also have to offer massive amounts of cash-backs or other incentives, to drive adoption and change user behaviour. But these investments may pay off, as their end goal will very likely be the mainstream adoption of digital services by the middle class (based on their needs), leaving MMPs to provide for low-income customers (non-smartphone users). In this scenario, MMPs’ existing business case goes out the window, as they will likely lose their most profitable customers. Over the last few years, this has already played out in India and Southeast Asia.

Needed: Long-Term Thinking

In light of this potentially grim future, how should MMPs respond? One thing they’ll need to do is to exchange short-term for long-term thinking: Most MMPs are taking a one-year view of their market and strategy, vs. new entrants who are taking a 10-year outlook. But can MMPs adapt and take a longer view? Some of them have already been investing in their current business models for five to seven years. In order to compete with new entrants, can they reset and invest in different approaches, with an eye toward the next five to seven years?

Further complicating this picture: Some MMPs are making significant profits (Safaricom in Kenya, Vodacom in Tanzania, MTN in Uganda, Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana, and Orange in West Africa, to name a few). What is their incentive to cannibalise their current profits? Now that they are under threat, it will be interesting to see how they react, if they do at all.

The outlook is not entirely bleak, however: These MMPs still have major assets, and they need to realise that fragmentation isn’t the way forward. Instead, they need to find a way to collaborate with each other. For MMPs, market share is fragmented because they use their own proprietary SIM cards and not the internet to enable customer payments. So their addressable market is solely limited to their MNO’s subscribers. (Some have launched apps to increase their addressable market, but a vast majority of their transactions still go through proprietary channels). In comparison, an OTT player’s addressable market is much bigger, including all internet users. The best way for MMPs to collaborate with each other is via interoperability, by interconnecting their services to allow customers of other MMPs to seamlessly transact between services. This is gradually happening: Orange and MTN have partnered to launch the Mowali mobile money platform in November 2018, and are yet to go live. Vodafone, which joined Facebook Libra and has since left the consortium, remains skeptical. But these efforts are happening far too slowly to make a difference.

Therefore, the billion-dollar question is: Who will MMPs choose to collaborate with? Will they work with other MMPs against the OTT threat? Or will they opt to partner with these new OTT players, waving a white flag, offering them their agent networks, and essentially becoming a utility instead of going out of business?

And there’s another equally important question that the industry must consider: How will this shift in the market impact low-income customers? While this battle plays out, expect more digital and financial exclusion over the next three- to five-year period, as those without smartphones will be left out. As the OTTs grab market share and MMPs are left with their less-profitable, feature phone-using customers, some will end up shutting down (as has been the case in India already), while OTTs focus exclusively on those with smartphones. To head off this threat, MMPs could start working to provide smartphones to their lower-income customers, with the aim of moving them toward purely digital transactions. This can be done using PayGo models, where customers make a monthly payment for a smartphone, which stops working if they stop paying. Some MMPs have started doing this, but it could raise a bigger problem: They may end up doing the hard work of digitising these customers, only for the OTTs to sweep them up. In light of these complex issues, it’s going to be really hard for the MMPs to win long-term – but they are dynamic and experienced companies in a constantly changing sector, so don’t write them off.

But however they respond, let’s hope that established MMPs will not wait until OTTs have captured all existing smartphone users before they focus on the emerging threat these new players represent to their business. If they wait too long, not only will their services falter, so will the progress the mobile money sector has made toward the fuller inclusion of underserved communities.

Arunjay Katakam is a fintech entrepreneur, futurist and the author of ‘The Power of Micro Money Transfers’.

Image credit: Markus Spiske

- Categories

- Finance, Technology