The Top Health Care Innovations of 2012: CHMI Releases its 2012 Highlights Report

In many emerging economies, the poor seek health care in a marketplace that lacks coherent systems. Unsure of where to seek proper treatment or unable to pay, patients often skip the doctor and self-diagnose, then head straight to the pharmacy or other drug seller to purchase their medicines. Even then, the patient has little idea of the quality of the drugs, or if they will even be in stock at a given drug outlet.

Yet out of this chaotic health market, many creative solutions have arisen to help consumers access appropriate treatments.

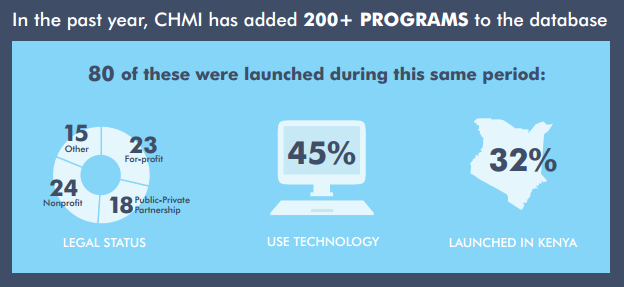

In Highlights: 2012, the Center for Health Market Innovations (CHMI) identifies a number of new trends in solutions that aim to improve the quality, affordability and accessibility of health care for the poorest and most vulnerable. These new approaches are being pioneered by social enterprises, nonprofits and governments to better organize, finance, and regulate the delivery of private-sector healthcare.

Rapid Growth in Primary Care Chains and Franchises

One of several notable areas of growth is the emergence of networks of private clinics, both for-profit and not-for-profit, delivering primary health services. At CHMI, we have identified and profiled 42 of these franchises and chains, approximately a third of which have launched in the past three years.

In order to provide sustainable, affordable, and quality primary care in low-income communities, these chains and franchises are experimenting with new business models and operational strategies. For example:

- Since time constraints force many people to forgo healthcare, Sehat First in Pakistan includes a general store in all of its clinics so that patients can pick up groceries and soap when visiting the doctor.

- Viva Afya (formally Carego Livewell) in Kenya uses a hub-and-spoke model to keep costs manageable. The hubs contain a clinic staffed by fully licensed and qualified medical doctors, along with a pharmacy and diagnostic laboratory. The spokes are staffed by qualified clinical officers and registered nurses and are electronically linked to the hubs for medical referrals and advice.

- In Mexico, Primedic helps promote preventive care and avoid major month-to-month revenue fluctuations by offering customers a membership scheme that gives them access to unlimited primary care consultations for only US$10 per month.

Extending Health Care to Remote Areas

H

CHAT’s use of camels is part of the larger trend of mobile care. Not to be confused with mobile health or mHealth (the use of information technology in health care), mobile care extends health care to people beyond the reach of static facilities. Mobile care can be provided with livestock, cars, trucks, bicycles, boats and motorcycles, carrying anything from a simple health worker to fully mobile cardiac catheterization labs. No matter the form, this model can serve many more people with the same equipment, helping to recover operating costs and more efficiently utilize staff time.

CHMI has identified close to 100 mobile care programs, most of which use one of the following three models:

- A number of organizations, such as the Islamia Eye Hospital, set up health camps – temporary locations to diagnose and refer patients to other facilities – to provide basic health education and preventive care to hard-to-reach populations.

- Using a slightly different model, Jacaranda Health runs a mobile maternal clinic that returns to various locations on a periodic basis, allowing them to provide longer-term care to expecting mothers.

- Other organizations run what are essentially traveling hospitals. In Peru, Pro Mujer provides dental and sonogram services out of vehicles that have converted into consultation units.

Building a Business Model to Last

CHMI’s new report identifies a number of other trends, including:

- Voucher schemes to improve a woman’s ability to pay for reproductive health services

- Programs that use phone-based clinical decision support software to help clinic staff and community health workers accurately diagnose and treat patients

- Networks like the BulshoKaab Pharmacies Network in Somaliland, which provide training, monitor service quality, and use common branding so that customers can easily identify them

The programs employing these solutions range greatly in size, from those covering single villages to those that affect whole countries. Similarly, while some of these programs have achieved sustainable models, others are heavily reliant on donor aid.

It remains to be seen whether all of these market-based organizations have staying power, and the potential to scale and deliver quality health services to large numbers of people in low- and middle-income countries.

As these and other groups test out new approaches, CHMI will continue to share promising practices and highlight experimentation with alternative business models. We believe that this information will be crucial to ensuring the diffusion of effective programs and the success of these business models as a whole.

Learn more about new practices in health markets around the world in Highlights: 2012. Visit HealthMarketInnovations.org to download the report and see photos of more than 15 of the world’s most innovative health models.

Editor’s Note: Trevor Lewis works with the Results for Development Institute, where he focuses primarily on health care financing and delivery innovations through his work on the Center for Health Market Innovations (CHMI). This is his first post as a NextBillion guest writer.

- Categories

- Education, Health Care

- Tags

- research