Verifying a Need: SimPrints wades into ‘identification crisis’ in health care, seeking global scale

UNICEF has declared a child’s right to an identity to be a fundamental human right. To those of us who live in rich countries, however, the right to an identity is not something that immediately makes a lot of sense. When we go to a clinic or bank, we simply need to show our driver’s license or birth certificate to connect instantly with our health records and financial history. The simple but meaningful act of providing ID is something we take for granted. It scarcely occurs to us that being unable to formally identify ourselves would severely hinder our access to basic rights and services. Yet this debilitating lack of identification is pervasive in the developing world.

In 2000, 40 percent of the births in developing countries were not registered by any form of identification. This statistic rises to more than 70 percent in the least-developed countries. Many development organisations therefore face a basic problem: The inability to name, locate and recollect those they are trying to help.

It was to this “identification crisis” that the internationally recognized NGO, Medic Mobile, challenged Cambridge University students to find a solution, through its 2012 Global Health Hack Challenge.

The winning idea came from Toby Norman, a Ph.D. student working in Bangladesh’s development sector, and soon produced SimPrints, which I co-founded. SimPrints has evolved, with the help of the Cambridge community and partners in Bangladesh, into a startup social enterprise.

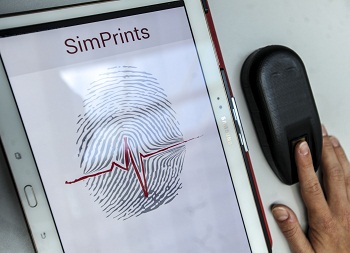

During the two years since that Hack Challenge, SimPrints has developed a pocket-size fingerprint scanner that instantly links an individual’s fingerprint to his or her health records. The Bluetooth-enabled scanner allows health workers in the field to make better decisions by providing immediate and reliable access to critical medical information.

During the two years since that Hack Challenge, SimPrints has developed a pocket-size fingerprint scanner that instantly links an individual’s fingerprint to his or her health records. The Bluetooth-enabled scanner allows health workers in the field to make better decisions by providing immediate and reliable access to critical medical information.

(A focus group of health workers with SimPrints scanners in Gaibandha, left.)

A simple finger swipe is all it takes to find out, for instance, which vaccines someone has received and which remain to be administered.

The software plugs into virtually any mHealth tool, allowing the SimPrints system to integrate easily with existing health systems. mHealth – the use of health care software on mobile devices like smartphones – has already revolutionised health care systems, and most countries support at least four mHealth initiatives. However, they are still limited by and vulnerable to misidentification arising from common community names, unknown dates of birth and human error.

The use of biometrics to tackle this problem has the potential to drastically reduce record-keeping errors, processing times and fraud, and has been recommended by the World Health Organization for preventing patient misidentification. While in some cases biometrics can enable anonymity by substituting names and addresses for fingerprints, privacy concerns reasonably exist.

SimPrints works to prevent the potential for abuse in a number of ways. We employ the same high-level encryption used in online banking. Furthermore, our scanner never stores or transmits the actual fingerprint, instead translating specific points on the print into a coded string of numbers that cannot be reverse-engineered into a fingerprint image.

Though privacy remains a top priority for us, we believe that the potential for biometrics misuse is not reason enough to prevent its utilisation to empower individuals and save lives. In fact, much of the world has already entered an era of biometrics, with nearly a billion individuals in developing countries using biometric ID for purposes ranging from elections to health care. The developing world swiftly adopted mobile phones to leapfrog the lack of land-phone infrastructure, and biometrics is doing the same for identification.

Though privacy remains a top priority for us, we believe that the potential for biometrics misuse is not reason enough to prevent its utilisation to empower individuals and save lives. In fact, much of the world has already entered an era of biometrics, with nearly a billion individuals in developing countries using biometric ID for purposes ranging from elections to health care. The developing world swiftly adopted mobile phones to leapfrog the lack of land-phone infrastructure, and biometrics is doing the same for identification.

(SimPrints in action, right. Photo by Cambridge News)

As the idea for SimPrints took root, we decided to gauge the real need for this technology. We spoke to dozens of organisations which employed health workers, and the interest they showed was overwhelming. We started receiving letters of interest from NGOs, social enterprises and governments. Having taken advice from industry gurus, we sought to develop our product using a human-centred design approach, i.e. focussing intensely on the needs of the workers who would use it in the field.

Related article: A Visionary Approach to Financial Inclusion: Nachiket Mor discusses his groundbreaking plan for universal financial access in India

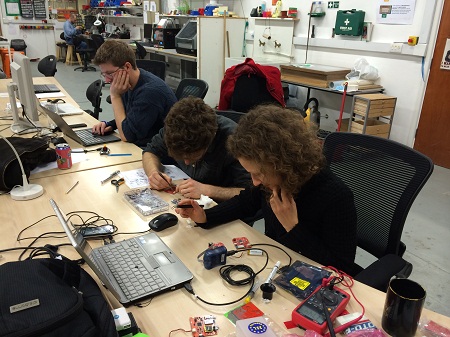

User experience became our obsession, and with barely enough money to finance our operations, we put together a working prototype and an array of diverse casings, and set off for Bangladesh. There, we conducted dozens of interviews and focus groups at every level of the development sector, absorbing the experience of patients, health workers, health worker managers, project leaders and executives.

We left Bangladesh realising how much more there was left to do. There were pros and cons to every type of scanning sensor, fingerprint extraction algorithm, circuit board design, etc. The work has been daunting, but recognizing the challenges we faced early on stood us in good stead. It was one aspect of our enterprise recognized by the judges who awarded us, a group of four students, the funding we needed to take the next step.

We left Bangladesh realising how much more there was left to do. There were pros and cons to every type of scanning sensor, fingerprint extraction algorithm, circuit board design, etc. The work has been daunting, but recognizing the challenges we faced early on stood us in good stead. It was one aspect of our enterprise recognized by the judges who awarded us, a group of four students, the funding we needed to take the next step.

(Co-founders Tristram Norman, Daniel Storisteanu and Alexandra Grigore developing SimPrints prototypes in their Makespace workshop, left.)

In August, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation granted SimPrints $250,000 U.S. as part of an innovation prize to reduce maternal and newborn deaths. This was then matched to by Cambridge-based ARM Ltd. In partnership with Johns Hopkins University’s Global mHealth Initiative and with BRAC, the world’s largest NGO, we are using this money to optimise the SimPrints system and conduct a full pilot study in Bangladesh.

While this seed money is a great start, it doesn’t remove the need to create a competent and financially sustainable business model to drive the product forward. Global impact requires global scale, and so we’re building a technology social enterprise to bring these tools to market.

The trade-offs between different approaches here are complex. For-profit social enterprises can recruit talent with equity and potentially access large VC capital down the line to accelerate their impact, but lack access to many of the foundation and donor funds their nonprofit colleagues can rely on. Yet these funds are a double-edged sword for nonprofits as well, at times enabling you to reach poorer consumers but at others distracting you from truly focusing on the needs of your end-users and creating a model that sustainably serves all of them. As we navigate these issues, ultimately our philosophy and values need to be the fixed point that guides our course, simply encapsulated in SimPrints’ first value: “Impact over profit.”

The road ahead is still long, but we now have the necessary tools to make a device that is as accurate, cost-effective and secure as possible, and then use it to give everyone the right to an identify and the better health care that comes with it.

Daniel Storisteanu is a co-founder of SimPrints.

Toby Norman also contributed to this post. He’s a Gates Scholar who has worked with doctors and community health workers throughout Africa and South Asia for more than seven years on health service delivery initiatives.

- Categories

- Environment, Health Care, Social Enterprise