NexThought Monday – 12/15/14 – The Over-The-Counter Paradox: Dependence on agent transactions is holding digital finance back – but could agents also move the sector forward?

I’m worried about over-the-counter (OTC) transactions. Before I explain why, let’s quickly define the term, and how these transactions help facilitate digital financial services in different markets. In a nutshell, OTC transactions are mobile money transactions that are facilitated by a provider’s agent network. The common factor is that at least one end of the transaction – either on the sender or the receiver’s side – involves an agent interaction rather than happening directly through a digital wallet. OTC transactions may involve the direct deposit of funds by the agent into the end-user’s digital wallet, as is common in Kenya, or the transfer of money from one agent to another agent, with or without identification, as happens in Pakistan and Bangladesh respectively.

There are clearly very good reasons that providers use agents, including the support they provide to customers who may be unaccustomed to the service. There are even some go-to market reasons that might entice providers to want an OTC service. But the long-term downsides for all, except agents, concern me greatly.

The Cause for Concern

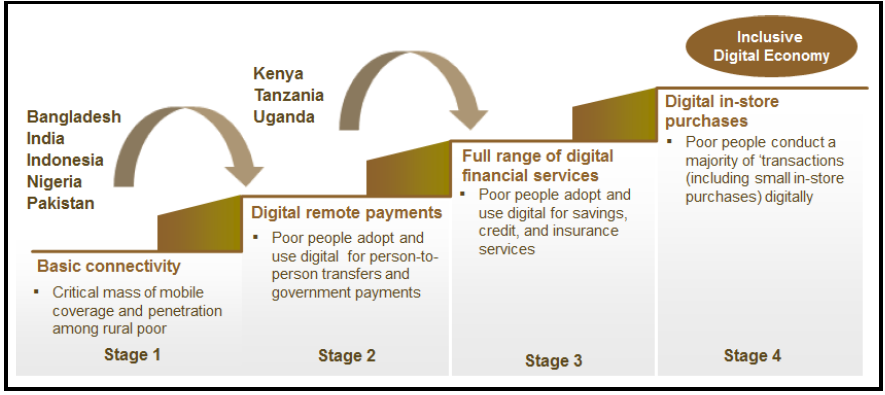

In their December 2012 paper “A Digital Pathway to Financial Inclusion,” Dan Radcliffe and Rodger Voorhies of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation outlined how basic mobile connectivity and digital remote payments are the first two necessary steps towards an inclusive digital economy. Yet rather than moving beyond these steps, I believe there is a very real risk that providers leveraging OTC transactions to reach massive scale will get caught in the OTC trap. They will find (and in many cases have found) that:

-

their services, and the customers using them, are entirely dependent on agents;

-

very few users register and fewer use mobile wallets, which can allow them to store value on their phones and establish a deeper financial relationship with providers;

-

as a result, no ecosystem develops.

Providers and their customers will then be stuck in stage two, the payments-only step of Radcliffe and Voorhies’ stairway to an inclusive digital economy.

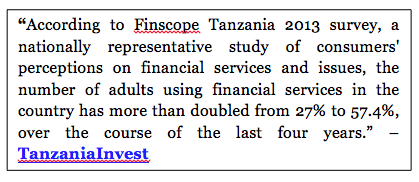

This is not the level of inclusion we are all seeking through digital financial services. Payment services are immensely valuable for the poor, no doubt – but access to payments does not result in what most people would define as “financial inclusion.” And yet access to basic mobile money payments is already effectively being equated with financial access (see the box for one example of many).

Once again, we are risking what some experts describe as “low equilibrium financial inclusion.” We have already seen how ineffectual it is to ask the poor to run the marathon out of poverty on one leg, thanks to the growing body of short-term RCT studies that suggest microcredit alone has limited impact. Countless studies, most notably The Portfolios of the Poor, have documented the poor’s needs for a range of financial services encompassing savings, credit, payments and insurance. Offering the single leg of payments and asking the poor to run the same marathon will have similarly limited results.

Once again, we are risking what some experts describe as “low equilibrium financial inclusion.” We have already seen how ineffectual it is to ask the poor to run the marathon out of poverty on one leg, thanks to the growing body of short-term RCT studies that suggest microcredit alone has limited impact. Countless studies, most notably The Portfolios of the Poor, have documented the poor’s needs for a range of financial services encompassing savings, credit, payments and insurance. Offering the single leg of payments and asking the poor to run the same marathon will have similarly limited results.

The Root of the Problem – and a Potential Solution

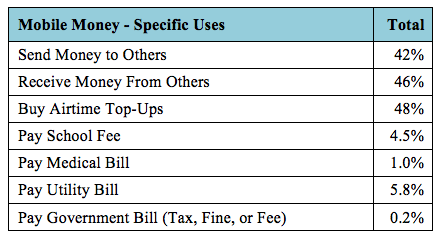

Indeed it may be the lack of credible wallet-based product offerings that is driving the predominant use of OTC transactions in many countries. If providers are unable to build and roll out products that offer real value to customers, then registering a wallet may well be  an unnecessary and time-consuming exercise – not just for the agent, but for the end user as well. After air time top-up, the most obvious use of wallet-based services provided by mobile network operators (MNOs) is bill payment. So the limited use of these services by Kenyan adults (of whom 68 percent are registered mobile money users), as described in Intermedia’s Financial Inclusion Insights, is surprising and alarming (see Table). The same survey noted that for all the publicity invested in it by Safaricom, only 15 percent of Kenya’s active mobile money users had used M-Shwari, the mobile savings and credit product it launched to add value to M-PESA. Clearly sign-up and use are very different things, as MicroSave had surmised when we wrote M-Shwari: Market Reactions and Potential Improvements.

an unnecessary and time-consuming exercise – not just for the agent, but for the end user as well. After air time top-up, the most obvious use of wallet-based services provided by mobile network operators (MNOs) is bill payment. So the limited use of these services by Kenyan adults (of whom 68 percent are registered mobile money users), as described in Intermedia’s Financial Inclusion Insights, is surprising and alarming (see Table). The same survey noted that for all the publicity invested in it by Safaricom, only 15 percent of Kenya’s active mobile money users had used M-Shwari, the mobile savings and credit product it launched to add value to M-PESA. Clearly sign-up and use are very different things, as MicroSave had surmised when we wrote M-Shwari: Market Reactions and Potential Improvements.

But ironically, for a sector that built its mobile money success on the personal contact provided by agent networks, MNOs have reversed that approach when it comes to next generation digital financial services like savings and credit. In many markets, these services are being offered exclusively over the handset, with agents performing cash-out but not involved in the enrollment process or subsequent support services. Though this saves the MNOs money on agent commissions, it detaches these new products from the agent channels that have been defining features of successful mobile money roll-outs.

As Mike McCaffrey and Anastasia Mirzoyants explain in their blog The Human Touch Required to Evolve Digital Finance, signing up for mobile savings, credit or insurance products requires a lot more trust in the provider than immediately verifiable money transfers do, and it can be a tough sell for a digital system that most people still do not understand. By leveraging the customer trust their agent networks have earned, MNOs might have more success convincing mass-market customers that mobile wallet products will work for them and actually address some of their specific problems. Instead, given the business models the telecoms have developed that encourage channel detachment for these products, they may be providing an opening for their bank competitors to step in by slowly and steadily investing in the human touch that brings the trust required to take mobile finance to the next level.

Graham A.N. Wright founded MicroSave and is currently its group managing director.

- Categories

- Uncategorized