Beyond ‘Africa Rising’ – The Emergence of the Not-Quite-Middle Class

The past five years or so have seen a number of exuberant studies and predictions that Africa’s rapid growth was creating a new middle class. This new group of consumers, it was argued, would become an engine of domestic demand, reducing reliance on exports and sustaining economic growth in the same way as they have in China. There were even predictions that this new middle class would transform governance and politics. This was the hopeful and optimistic story of “Africa Rising.”

The imagery was so powerful that the IMF named a conference after it. Opening that conference just two years ago, IMF chief Christine Lagarde told delegates, “Africa’s success journey has been truly remarkable,” and that “Africa’s future lies with itself and its people.”

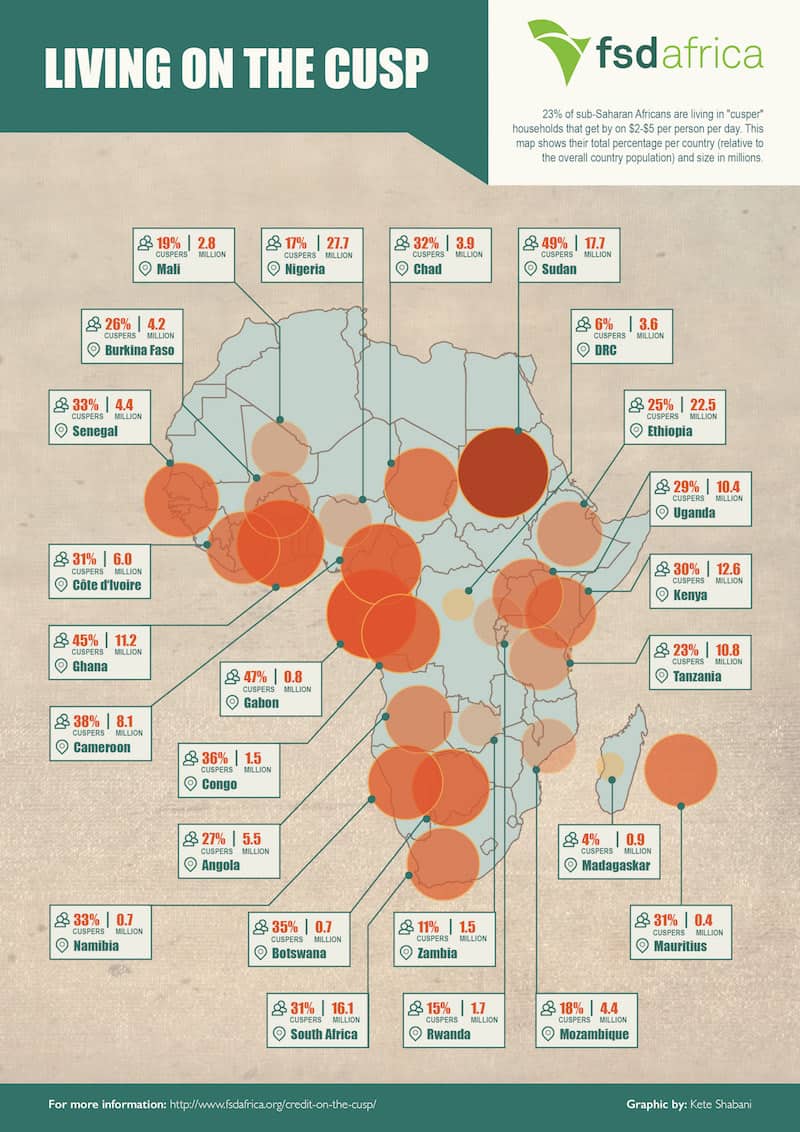

But if we really break down Africa’s population pyramid, what we see is not a rising middle class but rather a new group that lives on the cusp between poverty and the middle class, getting by on $2 to $5 a day. While they have emerged from absolute poverty (less than $2 a day), they still lack the kinds of assets, job security, purchasing power and stability we associate with middle-class livelihoods.

In Africa’s political and economic discourse, this new “cusp” group has been relatively ignored, drowned out by the “Africa Rising” narrative. Yet this group is large: World Bank data indicate that more than one in five (23 percent) of sub-Saharan Africans, or 227 million individuals (including both cusp earners and their families), belong to this group.

It’s true that this group could be an engine of growth through consumer spending, if their household budgets shifted away from their current overwhelming focus on food. And they represent an important and viable market for financial service providers and social enterprises targeting underserved, lower-income people. Generally, they are urban, connected and literate. So this group is increasingly politically important. And while they may not reach the middle class themselves, their children have a better shot. Building a true middle class in many Africa countries depends on cuspers’ success in raising healthy, well-educated children. So this generation could be the ones that provide the ladders of opportunity to the next.

It’s true that this group could be an engine of growth through consumer spending, if their household budgets shifted away from their current overwhelming focus on food. And they represent an important and viable market for financial service providers and social enterprises targeting underserved, lower-income people. Generally, they are urban, connected and literate. So this group is increasingly politically important. And while they may not reach the middle class themselves, their children have a better shot. Building a true middle class in many Africa countries depends on cuspers’ success in raising healthy, well-educated children. So this generation could be the ones that provide the ladders of opportunity to the next.

Recognising the importance of the cusp segment, FSD Africa commissioned Bankable Frontier Associates (BFA) to take a deeper look at the lives of people in this group, commissioning a new round of in-depth interviews with 90 cuspers living in cities in three diverse African countries: Ghana, Kenya and South Africa.

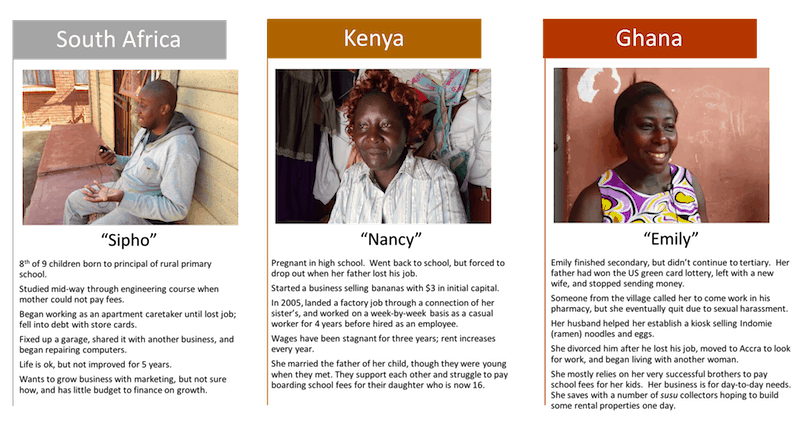

These are a few of their typical stories:

Figure 1: Meet the Cuspers – Profiles of three of our 90 cusper respondents, struggling to find a foothold in the middle class.

Through these interviews, it became clear to us that the economic future of cuspers is precarious and uncertain. Their budgets are constrained, with food expenditures often still accounting for more than half of the household budget. A significant share of their spending also goes toward transport and housing. They are anything but middle class. Having such a large share of their budgets tied to food and energy-related products makes them particularly vulnerable to price rises caused by inflation and exchange-rate volatility. Theirs is a fragile existence, and by no means do they have a secure middle-class status.

Two years ago, Lagarde told the “Africa Rising” summit that “today, only one in five people in Africa finds work in the formal sector. This must change.” Yet cuspers still straddle both the formal and informal labour markets, and where they have formal work, it is typically low-skilled labour in a context of high unemployment. In Ghana and Kenya, cusp earners are less likely to have written contracts compared with their wealthier counterparts. In South Africa, cusp workers are more likely to work for limited or unspecified hours compared with middle-class or wealthy workers. Many cuspers in formal labour markets see their well-being plummet during periods of economic downturn and job loss. They lack the cushion of redundancy payments or the debt-bearing capacity enabled by collateraliseable assets.

Where informal markets for goods and services are strong – like in Kenya – it is more possible for cuspers to rebound and start again with very small amounts of starting capital. But that kind of resilience may diminish as economies modernise and formalise. And even in Kenya, it remains extremely rare for cuspers to build a business that can endure across many years, move into value addition, become formalised, and perhaps even hire employees.

When Lagarde told the “Africa Rising” summit: “Africa’s greatest potential is its people,” she was not wrong. But the bottom line is that while Africans are indeed rising, they are not rising as far or as fast as we once hoped. Instead of a confident new group of stable middle-income earners, what we are seeing is the emergence of a not-quite-middle class. The emerging cusper group, making $2 to $5 a day, may get there eventually – but they may also slip back, or simply cycle in and out of absolute poverty.

Photo credit: Paul, via Flickr.

Julie Zollmann is a research consultant who works independently and with the niche consulting firm, Bankable Frontier Associates.

Credit on the Cusp is a project of FSD Africa that studied the credit market experiences of urban cuspers in Ghana, Kenya, and South Africa, using insights from their stories to help build a new vision for healthy credit market development in sub-Saharan Africa. The full report will be published 8 September 2016. More information is available here.

- Categories

- Social Enterprise