Can Access to Smartphones Bridge the Digital Divide in Sub-Saharan Africa?

Good news! Mobile phones can be a useful tool in the fight against poverty, increasing both household income and consumption. In a 2018 randomized control trial (RCT) in Tanzania described as “the first pure RCT testing the effectiveness of mobile phones on poverty reduction,” researchers ran an experiment to understand if access to phones affected women’s economic status. The experiment assigned 1,352 women into four groups:

- The women in the first group received a smartphone.

- Those in the second group received a feature phone.

- The third group received a cash transfer of US $18 each—enough to buy a basic feature phone.

- The fourth (control) group was told that “they would be placed on a waitlist to receive their items [presumably phones] in year two of the program.”

The study showed that women’s access to feature phones and smartphones increased their monthly household consumption by 16-24% (US $12-20) – mainly due to their use of the phones in small businesses and for mobile money transactions. As the researchers put it, these increases likely feel significant, since the women in the study had household consumption of just $2.59 per day on average. With basic phones costing $18 and smartphones $65, these results suggest that mobile phones offer a very high return on investment, and could provide a cost-effective path to poverty reduction.

However, the research also found that 31% of the feature phone group and 26% of the smartphone group no longer owned a phone at the end of the experiment (after 13 months), reporting their project phone was either lost, broken, stolen or sold. Additionally, many women in the smartphone group had only a feature phone at the end of the experiment, having traded or sold their project smartphones. Only 34% of the women in the smartphone group still had it.

These results highlight the potential of mobile phones as a poverty alleviation tool. But to reach that potential, it’s important that these phones are able to bridge the digital divide, becoming accessible to, and used by, the underserved people who can benefit the most from these technologies. The factors we’ll discuss below can increase — or limit — the usage of smartphones and other mobile devices in low-income communities in sub-Saharan Africa.

Both quality and (relatively) cheap smartphones are increasingly available in East Africa

The falling price of smartphones has made them increasingly available in East Africa and other emerging markets. But as a 2016 Mozilla report highlights, cheap smartphones have limited RAM, which prevents them from running many of the apps that can make them useful for agriculture, enterprise and mobile money transactions. These problems persist even today. Moreover, these low-end devices also typically have hopelessly short battery lives, screens that shatter easily, and a persistent problem with “fat finger error” that makes them almost unusable.

However, efforts are underway to get better quality smartphones into the hands of the poor. For example, in 2020, Safaricom partnered with Google to launch an affordable 4G-enabled smartphone in Kenya, which can be purchased in installments. Customers pay a down payment of around US $9, followed by daily payments of as little as KES 20 (around US $0.16) a day for nine months — so the phone’s total cost is KES 5,999 (around US $50). But even efforts like this may not be enough.

The cost of data can be a crucial limiting factor

Data is expensive across Africa. For example, data in Nigeria is more than twice as expensive as in Pakistan (see table to the right), which has roughly the same population — around 220 million.

This stops many from using the internet or apps on their mobile phones. And even those who use data often have what Jonathan Donner calls “a metered mindset, in which people don’t surf and browse, but rather sip and dip.”

Consequently, notes Donner, most data packages purchased are small, under 10 MB or between 10 and 50 MB. Data packages also tend to be smaller among rural users. And “sipping and dipping” instead of “browsing or surfing” limits discovery, reliability of contact and deep engagement with digital resources.

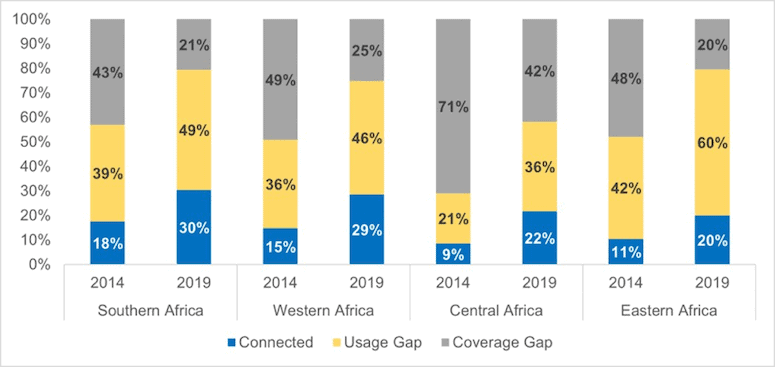

The result is a significant usage gap between those who have internet coverage and those who actually use it, which has persisted even as the coverage gap has reduced, as seen in GSMA’s work on this (see bar chart below).

Mind the usage gap

The gap in mobile internet usage disproportionately affects the underserved — that is, the rural population, women and those with low incomes. Sub-Saharan Africa continues to face a large gender gap (37%) and rural-urban gap (60%) in mobile internet use. GSMA highlights that a lack of awareness of mobile internet is a key barrier to adoption in the low- and middle-income countries they surveyed in the region, where almost 25% of adults were not aware of it. But for those who are aware of mobile internet, the most significant barrier to usage is a lack of literacy and digital skills, followed by concerns about affordability and perceived relevance.

Three factors have primarily driven progress in addressing the usage gap. First, handsets have become more affordable — see MSC’s article “Mobile Internet Access — The Next Frontier for ‘Tech’,” which discusses the potential of “smart feature phones” in this context. Second, 3G and 4G coverage has been extended. Third, network performance has improved — see our analysis of “The White Spaces of the Digital Divide: 3G+ Haves and Have-Nots” for a discussion of this.

New business models to address the affordability of smartphones

Several attempts, including the “$1 smartphone” from the (now defunct) company SocialEco, have been made to use advertising revenue to finance smartphones. But the restricted purchasing power of the poor limits the number and type of entities that seek to market to them. And users do not always respond positively to the inclusion of ads on their mobile devices.

The latest initiative to take this approach is KEIPhone, which provides free smartphones and solar chargers to unconnected women via an advertising-based revenue model, which it also employs to help users pay for data.

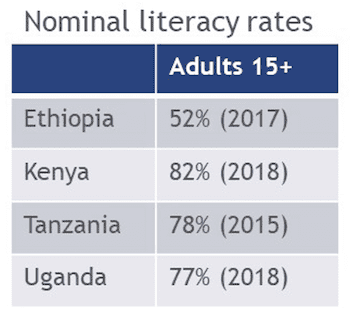

Lack of literacy and digital capability are significant barriers to mobile uptake and usage

Source: https://www.macrotrends.net

Economics is not the only challenge to the adoption and usage of mobile phones. Illiteracy, innumeracy and digital illiteracy also create barriers. This suggests that icon-based and Interactive Voice Response (IVR)-driven interfaces will be essential to increasing the self-initiated usage of mobile phones.

These multiple literacy gaps are widespread in sub-Saharan Africa. The assumption that those who graduate from primary school are literate and numerate is fundamentally flawed. Thus, these estimates of literacy rates (see the table we compiled to the right) significantly understate the problem — perhaps by as much as 100%. And numeracy presents an even larger challenge: FinScope Tanzania 2017 noted that in Tanzania only 71% of adults can add, 59% can subtract, 40% can multiply and 46% can divide.

As a result, users who lack these skills will need agent assistance and tailored interfaces that comprise icons or IVR systems — or both. In the longer term, IVR and natural language processing-based applications (think Siri or Alexa) may hold the key. However, these are not widely available—and even less so in regional languages.

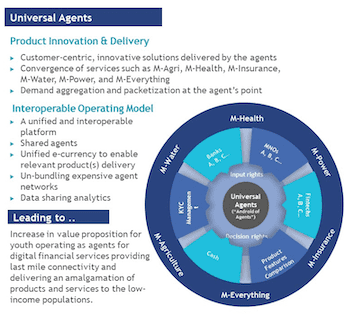

Right now, agents are the key

Based on the challenges discussed above, we may conclude that agents will need to assist with much of the shift to internet and app usage by poor communities, providing them with mentoring and assistance in using these tools. For years we at MSC have worried about agent-enabled over-the-counter transactions increasing risk and destroying providers’ business cases in mobile finance. Still, it is clear that we need to see agent assistance as an onboarding service and an on-ramp for the excluded and poorly served — whether they’re gaining access to mobile finance, or to mobile internet more broadly.

Agents can assist those who lack literacy or numeracy — or who simply lack confidence. They can provide guidance on what apps, products and services to use, and demonstrate how to use data-enabled services. Using agents in this manner enables the sharing of hardware resources (phones or tablets), allows customers to acquire guided and assisted internet access on demand without having to buy data packages, and facilitates community assistance and learning aimed at preparing the next generation of smartphone users.

Agents can assist those who lack literacy or numeracy — or who simply lack confidence. They can provide guidance on what apps, products and services to use, and demonstrate how to use data-enabled services. Using agents in this manner enables the sharing of hardware resources (phones or tablets), allows customers to acquire guided and assisted internet access on demand without having to buy data packages, and facilitates community assistance and learning aimed at preparing the next generation of smartphone users.

Finding ways to allow agents to provide these services on a profitable basis will be essential to the growth of mobile access — and mobile businesses. To do so will require a significant increase in revenue streams. MSC and a range of practitioners from East Africa outlined one way to achieve this in our 2017 article “A Strategic Approach for Next-Generation DFS Agent Networks,” in which we advocated a substantial broadening of the products and services agents offer, accomplished through a “universal agent” approach in which industry players serve customers through a shared agent network (see diagram to the right).

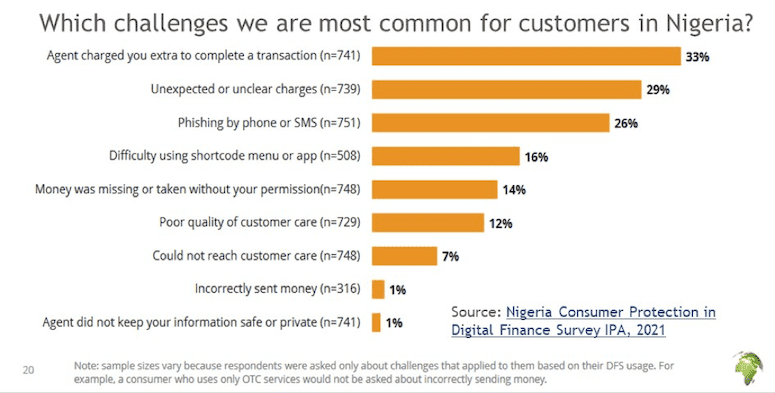

However, while agents offer many real advantages, they also raise several risks and consumer protection concerns that will require attention. For instance, the issues found in Nigeria by IPA in 2021 (see graph below) almost exactly reflect those found in Uganda by MSC and CGAP in 2015. These undermine trust and thus uptake and usage of digital financial services — with or without smartphones.

Smartphones and other mobile technologies are already making a substantial positive impact in emerging markets. But to maximize this impact, and avoid potential downsides, businesses and other key stakeholders will need to address the unique constraints experienced by these communities.

Editor’s Note: This article was voted by readers as one of NextBillion’s Most Influential Articles of 2022.

Amani M’Bale is a Senior Program Officer for East Africa at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and Graham A.N. Wright is the founder and managing director of MicroSave (MSC).

Photo courtesy of Global Devlab.

- Categories

- Finance, Telecommunications