Airbnb is Just the Beginning: The Sharing Economy Comes to Emerging Markets

Want to understand one impetus behind the emergence of the sharing economy? Consider these mildly shocking statistics:

- On average, the American home has nearly tripled in size over the past 50 years, and now contains about 300,000 items.

- In Britain, researchers found that the average 10-year-old owns 238 toys but plays with just 12 daily.

- The average American woman owns 30 outfits— in 1930, that number was nine.

Combine this astonishing volume of excess stuff with a widespread and growing need for additional income streams – then throw in the proliferation of smartphones and mobile platforms that allow people to easily share their underutilized belongings. The result: a buzzworthy new industry with platform provider revenues of $18.6 billion – a number that’s predicted to double by 2022 – and users that number 44.8 million adults in the United States alone, a total that’s expected to increase to 86.5 million by 2021.

The drawbacks of the Uber model

As smartphone ownership continues its rapid growth, the sharing economy’s effect on livelihoods around the world is a story that’s quickly unfolding – one with far-ranging implications for dozens of industries, governments and individuals. We spoke with April Rinne, a sharing economy expert based in Portland, Ore., about what this could mean for emerging markets. She emphasized that the concept of the sharing economy has been around for many years, and that it resonates particularly well in lower-income settings, where people have fewer physical assets and are already accustomed to shared usage. But she cautioned against hyping the sharing economy model or applying the term overzealously. “Everyone likes the word ‘sharing,’ so why not slap it on your business model? That’s overselling,” she said. For instance, she objects when a business claims to have launched “the Uber of” [insert random industry], as Uber doesn’t even profess to be part of the sharing economy, preferring to call itself a technology and logistics company more akin to Federal Express or Amazon.

In fact, Rinne says, an Uber-like approach to “sharing” not only dilutes the concept – it could also present risks that are particularly troubling for lower-income users. She cites the company’s efforts to encourage drivers to lease cars, rather than simply using their own vehicles. “Where is the underutilized asset that we’re sharing there?” she asks. Along with concerns about resource consumption and environmental impact, she says this sort of approach risks making the sharing economy mainly the domain of the relatively affluent – or exacerbating existing inequalities – in emerging countries. Instead, she defines the sharing economy as “an economy that’s based on access over ownership, and decentralized networks of people connected through new technologies” to share assets they aren’t fully using.

Putting these assets into shared use not only provides income, it reduces the waste of seldom-used purchases, and even brings people together. “Many real sharing economy platforms are able to build community in some way,” she says. “They’re able to bring people into relationship with one another. It’s not that you become best friends with the person you share your car with, but you do get to know what’s happening in your neighborhood better.”

evolving Applications in Emerging Markets

As the sharing economy model evolves, it’s becoming increasingly clear that “underutilized assets” don’t have to be limited to physical goods.

While attending the United Nations World Tourism Organization global conference on jobs and inclusive growth in Jamaica in November, I had a chance to speak with Shawn Sullivan, Airbnb’s public policy manager for Central America and the Caribbean. Airbnb is a prime example of a global company that makes the sharing economy possible. In case you’ve never used it, the platform allows for individuals to make money by renting out an unused room or property. It offers 4 million listings across 191 countries, according to the company, with the number of Airbnb users continuing to grow. In 2016, 30.4 million adults used the service in the United States, according to Statista. The number is expected to reach 60.8 million by 2021. Seventy-six percent of all Airbnb listings are outside traditional hotel sectors.

My interview with Sullivan took place right before the online hospitality giant released its report “Advancing Sustainable Tourism Through Home Sharing” during the conference. The report focused on how underserved communities in emerging economies can benefit from Airbnb’s people-to-people platform. During our conversation, he painted a picture of a world in which many low-income people can earn at least a side income through sharing economy services like Airbnb’s.

“I think ultimately what Airbnb allows people to do is … to unlock their most valuable asset, their home, and earn money from it,” Sullivan said. “In many countries around the world, in many markets – including Jamaica – the majority of our hosts are women. We promote inclusiveness. We promote this different way to approach travel and tourism that benefits local communities. … Ninety-seven cents out of every dollar stays with the host, which provides a great deal of empowerment. … Really when you look at the impact we’re having in local communities, it’s massive.”

According to Sullivan, that impact also extends to people without a home to share. In Jamaica, Airbnb is working with the government to promote tourism in Trenchtown, a place of extraordinary musical heritage to Jamaicans, but not necessarily a top destination for tourists, due to its high poverty. The company is attempting to establish “experiences,” in which residents are guiding cultural voyages for tourists, leveraging their local know-how and authenticity to generate much-needed revenue streams. “To be an experience host, you don’t have to have a home that you list on Airbnb, you can just do it,” he explained. “It’s been so far very successful in a lot of countries around the world. It’s something that we’re very proud of.”

“There are a lot of communities that have never really been able to benefit from tourism that now will be able to,” Sullivan added. “That’s how we view our mission, our role at Airbnb, and being able to use technology and our platform to target those communities or individuals that in the past have been pushed aside. It’s a way to empower people and communities.”

Local customs – local challenges

The travel sharing economy has unique potential in developing markets. According to the United Nations World Tourism Organization, tourist arrivals in emerging economies are projected to grow by 4.4 percent annually. Tourism is among the top two sources of export earnings in 20 of the world’s 48 least developed countries, and in some of these countries, especially small island states, it can account for over 25 percent of GDP.

But it’s not just global companies like Airbnb that are making their mark in the developing world. In South Africa, for example, Rinne said between Johannesburg and Cape Town alone there are a half-dozen shared-use transportation platforms that are owned and led by South Africans. For emerging markets, she said it’s important to adapt the platform to suit the local market. In the Middle East, for instance, women-only cars were adopted by ride-sharing platforms, because of cultural and religious prohibitions against unrelated women and men riding together.

According to Rinne, the availability of technology (or the lack thereof) may be the biggest limiting factor for sharing economy companies in emerging markets. Most sharing economy platforms require a smartphone or some kind of mobile device and a credit card to pay, she said. These are huge issues if mobile access is spotty or expensive and/or if most of the country is still not banked. She pointed to digital and financial access as two key bottlenecks that must be addressed for developing markets to more fully adopt sharing economy approaches.

But with the countless innovators addressing both of these challenges with increasing success, it seems likely that sharing economy models will continue to proliferate in low and middle-income countries, providing entrepreneurs, individuals and governments with financial and other benefits. A deeper understanding of the sector’s potential will help policy makers and development sector players ensure that its benefits extend more fully to low-income communities, from the homeowner to the hotelier.

Sonya Vann DeLoach is associate editor at NextBillion.

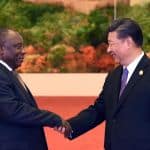

Top image: World Bank Group President Jim Yong Kim and Airbnb Co-founder Joe Gebbia speak on stage. Photos by World Bank via Flickr and Tero Vesalainen via Pixabay.

- Categories

- Technology