Banks Challenge M-PESA in Kenya: What their emergence could mean for the world’s leading mobile money market

Since the launch of Safaricom’s M-PESA mobile money platform in 2007, the story of digital finance in Kenya has been synonymous with the story of M-PESA. However, data just released from the Helix Institute of Digital Finance shows that this now seems to be changing, which is exciting to watch and also important to understand.

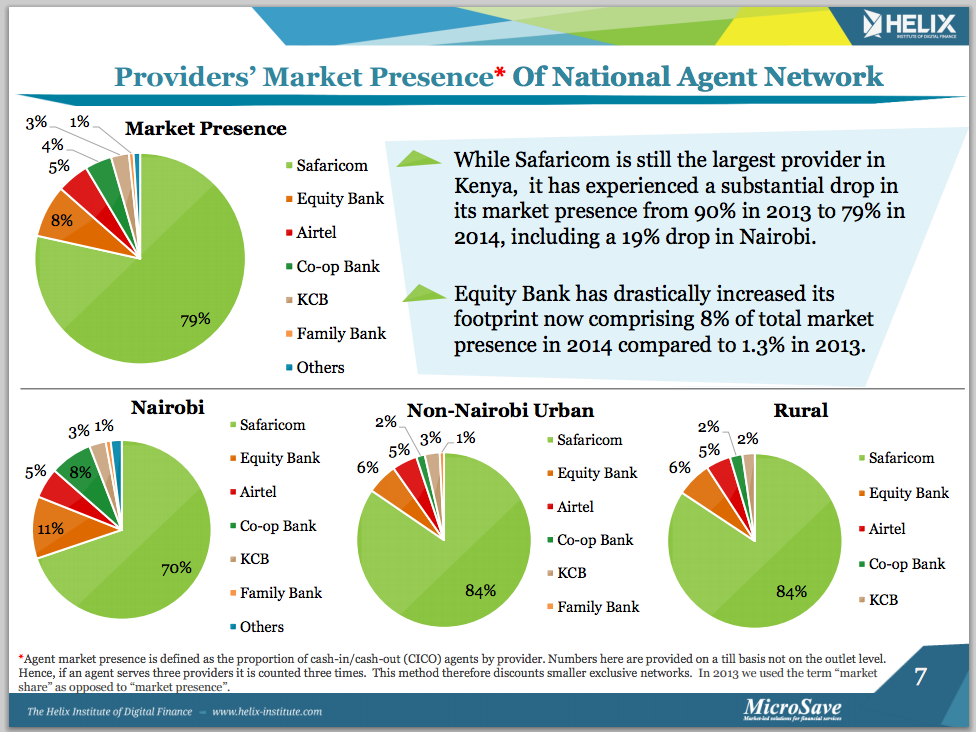

In 2013, the Helix Institute survey of more than 2,000 agents in Kenya showed that 90 percent of the agents were providing services for M-PESA. However, as shown in the below chart, that percentage declined to 79 percent in 2014, a drop of 11 percent. This means other providers in the market have been growing their agent networks at faster rates than M-PESA.

Who has been doing this and how? And what might this mean for the future of digital finance in Kenya?

Phenomenal Transmutation

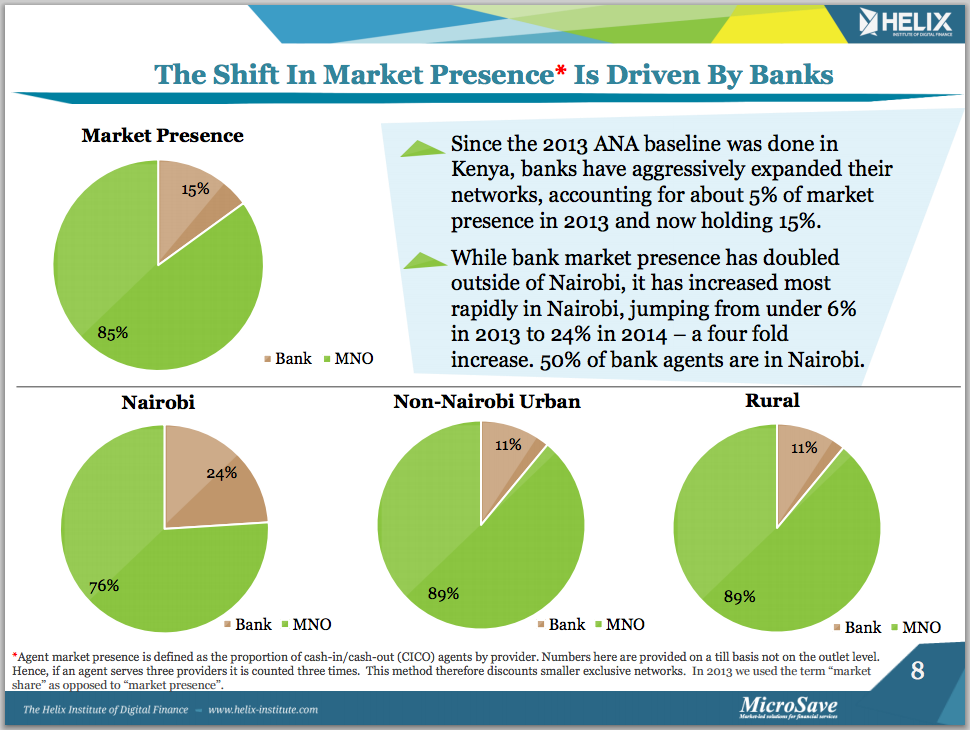

The first interesting insight is that the shift is not from one mobile network operator (MNO) to the other, which is most common in other markets given MNOs’ ability to scale quickly. Airtel Money in Kenya only increased market presence by one percentage point between 2013 and 2014, and the rest of the top six providers are banks. The shift is a transmutation of the network itself, from a network of almost purely mobile money agents, to one where bank agents also have a significant market presence. The below chart shows banks’ market presence grew threefold from 5 percent to 15 percent during the period. This aggressive expansion has been led by Equity Bank, which improved its market presence from 1.3 percent in 2013 to 8 percent in 2014, as well as Co-operative Bank and KCB.

Where and how the banks are expanding is also informative. There has been an accentuated transmutation in Nairobi, where banks have increased market presence four-fold, jumping from just under 6 percent in 2013 to 24 percent in 2014. Currently, 50 percent of bank agents are located in Nairobi. Further, while 73 percent of bank agents were exclusive in 2013, only 26 percent were in 2014, likely showing a new strategy to recruit existing M-PESA agents, as opposed to new retailers, which may have been a major catalyst for growth during that year. However, banks usually manage agents from their bank branches and therefore recruit in areas surrounding them, and it is unclear now how much longer a strategy like this will be sustainable, as suitable agents near bank branches become harder to find.

What’s on the Horizon?

While some may think that Kenya is headed in the same direction as Tanzania, with multiple providers holding significant market presence, we think the story is more complicated than that, as alluded to above. It does seem that banks will continue to grow larger agent networks in Kenya, and there was a similar trend in Tanzania of shared networks emerging first in the capital city and then expanding outwards. However, the big difference between what has happened in Tanzania and what is happening in Kenya is that the subsequent movers in Kenya are banks, while in Tanzania they are telecoms. This is important because banks in Kenya have very different abilities for continued growth, and also a great potential to create a more sophisticated ecosystem of service offerings.

Are Past Gains Indicative of Future Growth?

Banks usually have different business objectives for building networks, are subject to more restrictive regulation, and tend to design their networks differently in Kenya, commonly using a hub-and-spoke model based on their branches. In terms of business objectives, some banks just want to decongest their branches, and do not have the ambition for big scale that telecoms do. Further, regulation often makes it harder for banks to register new customers, which is the fuel they need to sustainably grow large numbers of agents quickly. Lastly, the hub-and-spoke methodology might work fine for a first tier of expansion around branches, however, expanding to the rest of the country becomes an issue at some point and requires a shift in strategy to scale further. Therefore, while there was an impressive growth of bank agents relative to mobile money agents between 2013 and 2014, it is unclear if this trend can or will continue moving forward.

The Potential for Real Evolution

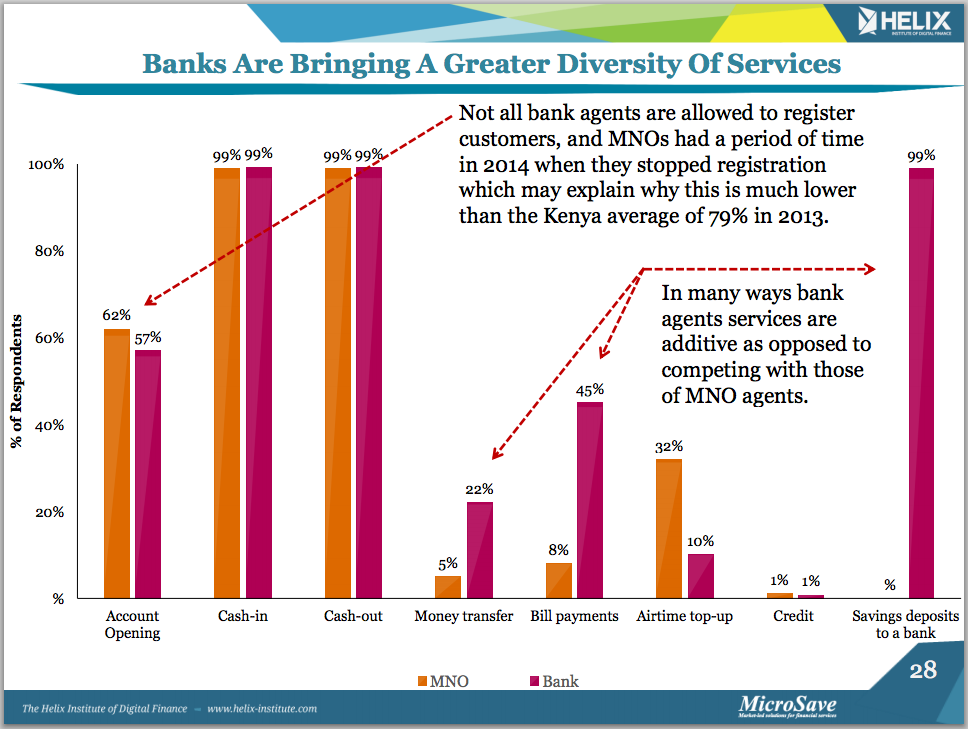

The other real difference with what is currently happening in Kenya is that this market shift has the potential to be an actual evolution in the utility of the system as opposed to just having more players competing to offer the same services, to the same people, over the same channels. The new bank players in Kenya seem to be expanding the transactional pie, as opposed to just further fracturing the existing one. Kenyan bank agents offer a different array of services to customers through the agent channel, as shown in the chart below, and transactional data shows that bank agents conduct significantly higher transaction values than mobile money agents, which means customers are using them differently. Hence, bank and mobile money agents do not necessarily compete. Therefore, banks and MNOs might be able to find ways to complement each other to further increase available services in the ecosystem and reduce the costs of offering them.

Conclusion

The shift in market dynamics in Kenya is exciting given how long it has been the story of a single player. It is still unclear if it will continue, but if it does, it seems that it will likely lead Kenya down a different, more dynamic path than other countries which have multiple players competing. Hopefully, the new services banks are offering to customers will be seen as beneficial to a more digital ecosystem, and partnerships (as opposed to price wars) will emerge. There is hope for this given the recent partnerships between Safaricom and CBA to offer M-Shwari, Safaricom and KCB to offer KCB M-PESA Account, and Airtel and Equity on the Mobile Virtual Network Operator. Given the difficult strategic operations and expenses associated with managing an agent network, areas like liquidity management, agent training, and monitoring might be good places to extend partnerships, effectively spreading the spirit of co-opetition between banks and MNOs offering mass market finance in Kenya.

Related Post: Kenya’s Mobile Finance Revolution Takes the Next Steps: Two new developments go far beyond mobile money

Editor’s note: This post was originally published on the Helix Institute of Digital Finance’s blog. It is cross-posted with permission.

Mike McCaffrey is a Principal Consultant and Jacqueline Jumah is a Manager – Strategic Operations for Digital Finance at MicroSave.

- Categories

- Uncategorized