Connecting With the Customer – When the Lines of Connection Do Not Exist

How we built and grew our social enterprise, WeFarm

There are more than 500 million smallholder farmers in the world and the majority of them live on less than $1 a day. Many social enterprises work with small-scale farmers to create services and products designed to lift themselves out of poverty, whilst creating a social, sustainable business in the process.

However, no matter how well-designed the product or service may be, reaching such a remote segment of customers is one of the harder commercial prospects. Typically, small-scale farmers are very difficult to reach, both in person and through marketing. So how does one begin to work with base of the pyramid farmers to promote products and services to them and/or to improve their livelihoods?

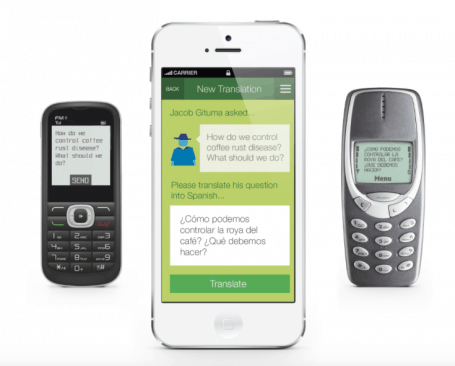

We created WeFarm, a social enterprise whose target market is small-scale farmers located in remote areas without Internet access, specifically to address this problem. We provide an SMS-based service wherein farmers can ask questions and receive crowdsourced answers from other farmers around the world. (Find out more about the model here).

There are now more than 43,000 farmers in Kenya, Peru and Uganda using WeFarm to improve their livelihoods. (We calculate this number based on the number of mobile phones using our platform, so it likely is a conservative estimate as many farmers share phones.) Working with BoP farmers as our main customer base is inherently challenging. But we have achieved excellent growth through persistence, hard work, and trial and error.

Here are a few lessons we’ve learned that might help anyone trying to make a difference with smallholder farmers.

Involve customers in the design process

We developed WeFarm between 2010-2014 by talking to tea, coffee and cocoa smallholder farmers in Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Peru, the Dominican Republic and Haiti. During this time, we tested the concept with farmers and tried to involve them in the design process as much as possible. Initially, we wanted to create an Internet platform or app. But the reality on the ground was that most people had (and still have) basic feature phones. So we ended up creating a service that uses SMS to crowdsource information.

Had we not spent time with our future customers, it’s highly likely that we would have created a working product that nobody wanted to use. My advice would be to get out there and work with the people you hope to empower. Be agile, try lots of different things, find flaws, and discover what will really work.

Had we not spent time with our future customers, it’s highly likely that we would have created a working product that nobody wanted to use. My advice would be to get out there and work with the people you hope to empower. Be agile, try lots of different things, find flaws, and discover what will really work.

Use a range of marketing tools to reach isolated small-scale farmers

Accessing isolated users is a big challenge for us. The majority of the small-scale farmers who use WeFarm have limited access to other traditional forms of media, all of which can make it more difficult for us to achieve the same exponential growth rate as other technology businesses.

However, a lot of WeFarm’s growth in this challenging environment came by trying many different forms of marketing to reach potential customers. The majority of successful sign-ups to our service come from radio shows, or educational programmes run in conjunction with co-operatives.

Other things that we have tried include training programmes in schools (so that young people could train their parents on how to use mobile tools), partnerships models, newspaper advertising and many more.

Seek local expertise where you need it

Recognising where you need local expertise is very important when working with small-scale farmers. There are so many differences between regions in each country, as a team we are constantly encountering situations where we require the expertise of locals. For example, with our recent launch in Uganda, we recruited a new part-time staff member who speaks Luganda to help us translate training materials and run workshops with farmers.

Utilise the power of peer-to-peer networks

One key factor in our success so far has been using a peer-to-peer model that relies on crowdsourcing information, which makes our business model globally scalable. A farmer in Peru can share useful information on how to prevent soil erosion with a farmer in Kenya, so that we become a content platform rather than a content provider. Wikipedia and Google are great examples of organizations and businesses that have executed this very successfully, but this model isn’t widely used in the developing world.

In order to end poverty we need to change the way we perceive those who are living in poverty. It’s been common thinking over the past decades that poor people need help, advice and guidance from the West. WeFarm challenges this thinking by giving people a voice. It’s been incredible to see how people are empowered by seeing that their knowledge is valuable.

Can you imagine how other sectors could benefit from a global community of people who have experienced challenges first-hand, and possess the knowledge that would truly help their fellow stakeholders to advance? The power of peer-to-peer is yet to be fully realised in developing countries, and I would urge more social entrepreneurs to research its benefits.

Above image: A training day at Kayonza Growers Tea Factory in Kunungu, Uganda. Photos by Camilla Gordon, courtesy of WeFarm.

Kenny Ewan is the founder and CEO of WeFarm.

- Categories

- Agriculture, Technology