Designing for Women: How COVID-19 Could Allow Government Payment Programs to Boost Women’s Economic Empowerment

Governments around the world are deploying government-to-person (G2P) cash transfer programs to assuage the urgent economic crisis caused by COVID-19. While they are under immense pressure to roll out this critical aid as quickly as possible, its delivery is complex. As of May 22, a total of 190 countries have introduced or scaled up cash transfer programs. But though these governments are providing vital support through these programs, they risk scaling systems that exacerbate current biases—deepening gender inequality and financial exclusion.

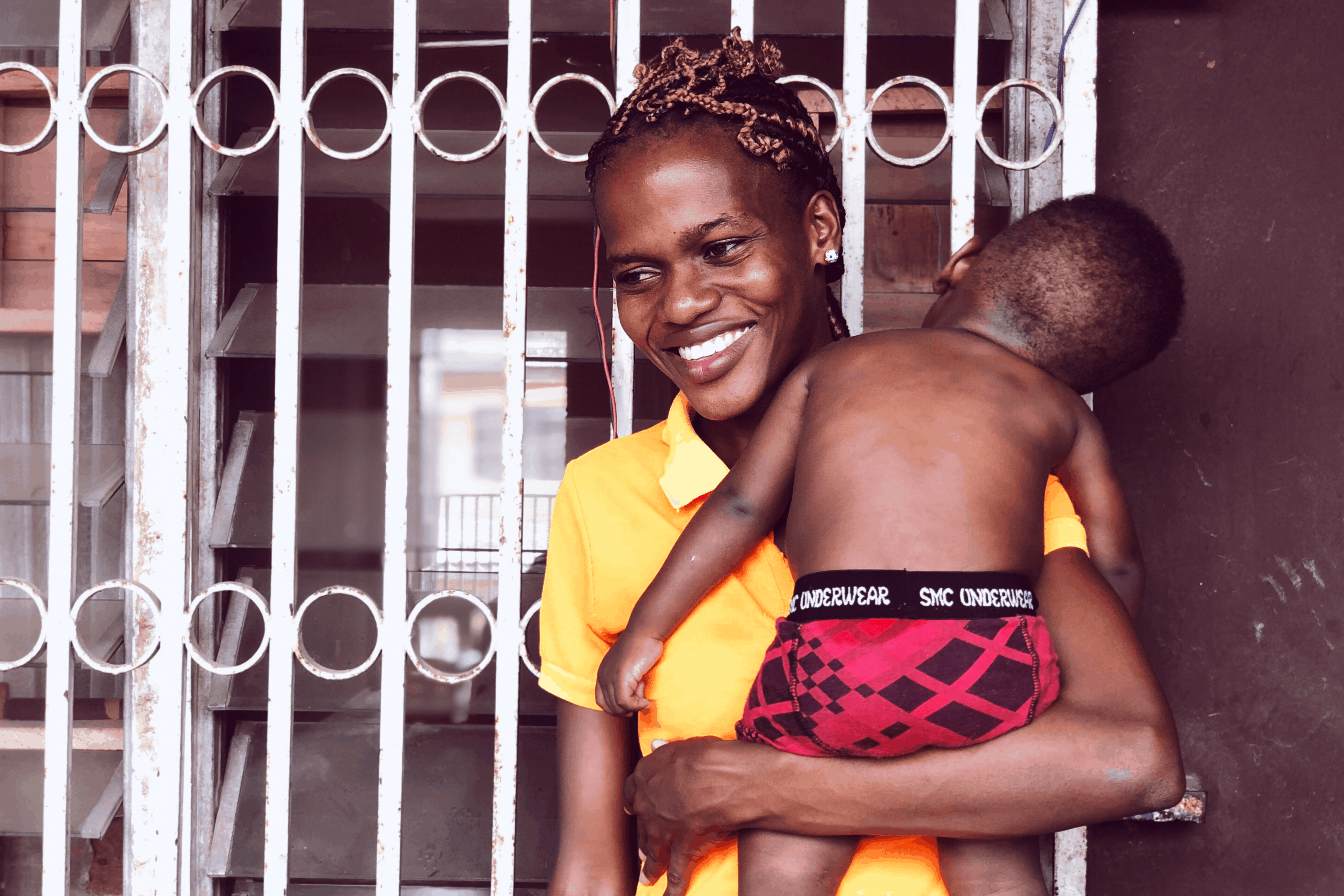

We know that women around the world are holding up their households in this crisis – saving more, caretaking more and experiencing greater disruption to their livelihoods, as compared to their male counterparts. This may be a moment to leverage the power of digital transfers to scale and reach more people quickly. However, unless this response is designed around women’s unique needs, they may end up being left behind in a system that is not made for them.

Globally, we are still in the first phase of the COVID-19 response, which is understandably focused on the speedy delivery of emergency funds. Yet the decisions G2P programs make now to integrate digital financial services (DFS) and tools for financial inclusion will yield lasting impacts, which can either be positive or negative. And over the course of the next few months, we will be entering a second phase of government response. In this next phase, we will have the opportunity to ensure that a focus on women’s financial inclusion is front and center — pioneering more gender inclusive G2P services at unprecedented scale.

Through our research, IDEO.org has seen how gender norms relax in moments of crisis. That means this crisis provides an unprecedented opportunity to supercharge financial inclusion. Imagine if COVID-19 pushed DFS to be unequivocally gender transformative — delivering cash assistance to those who need it most in an easy and accessible way, and promoting positive gender norms in the process.

In partnership with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, IDEO.org created the Women and Money program — a two-year initiative to deeply understand low-income, rural women’s experiences with DFS. Women and Money has spent the last year exploring this relationship in Tanzania, Northern Kenya, Nigeria, Pakistan, India and Bangladesh. From this research — a hybrid approach combining data science and human-centered design — we’ve gleaned several insights on the barriers to women’s economic empowerment and the building blocks of more gender-transformative services. These insights can help us build G2P systems in response to COVID-19 in service of emergency assistance and financial inclusion.

Insight One: Financial services often reinforce the message that women don’t belong.

This is often because women may not have the skills, assets or knowledge to fully participate in these services. For instance, Rahmi, from Pakistan, doesn’t read or write, and she doesn’t have a mobile phone. Our research shows that 67% of rural women in Pakistan share Rahmi’s literacy status and lack of phone ownership. Her husband has a feature phone, but he doesn’t allow her to use it. Rahmi has heard about DFS, but does not believe that these services are relevant to her.

To better serve women like Rahmi, digital G2P disbursements should offer options that do not require literacy, numeracy or the ownership of a mobile phone – and they should emphasize through messaging and outreach that this money is meant for her. Governments should build G2P programs to meet women where they are, leveraging the skills, assets and knowledge that they already have. If Rahmi were to hear about a government program to transfer funds to households like hers during COVID-19, she would likely not be confident using mobile money to get her disbursement. To address this issue, the Benazir Income Support Program in Pakistan, for example, switched to biometric verification to prompt disbursements, reducing reliance on literacy and decreasing fraud. Though many G2P programs may still rely on cash disbursements to ensure that beneficiaries are able to access their payments more easily, as these programs design their DFS solutions, they should keep these limitations in literacy, numeracy and phone ownership in mind.

In the longer term, G2P programs might consider providing greater women-specific support, which could include gender-sensitive assistance during onboarding, and continued support at cash-in/cash-out points. They could also develop DFS accounts that keep women updated on account activity but still allow for additional authorized users: This could keep the women account holders in control of their expenses, while giving them the option to designate proxy users when convenient. G2P programs can also identify, hire and train community ambassadors to field calls and questions around receiving or using payments. Our research found that women are more comfortable learning from other women, as they find them to generally be more patient and understanding teachers. So ensuring that women have the opportunity to fulfill community ambassador roles is key.

Insight Two: Money is the domain of men.

As a result, even those funds that are directed to women are likely to be controlled by male heads of households. For example, Oladiyin, from Northern Kenya, runs a small food stand with her husband. Although they put equal work and time into the business, her husband has the final say on what they do with their earnings. If left up to her, Oladiyin would invest her earnings in a cow, and put some cash away for savings. Yet she feels that most of the time, it is not for her to decide how money is spent. She does, however, feel empowered to make decisions around how to spend for the household.

Women are much more likely to feel agency over how to use funds when the money arrives in their accounts directly. That’s why campaigns and messaging around G2P disbursements should strongly identify and provide support specific to women. At a minimum, funds should be delivered to women’s own mobile wallet or bank account. A recent study on MGNREGS, a G2P program in India, found that payments into women’s own accounts (rather than their husbands’) led to 90% account ownership, compared to 43% for those who did not receive payments into their own accounts. This will likely require additional support, such as tailored onboarding to assist women in accessing these accounts.

We worked with our data science partners at DrivenData to determine the most significant drivers of women’s economic empowerment, and we found that contributing to household income is the biggest indicator. Depositing funds directly into women’s accounts can have the same effect.

In the longer term, G2P programs can ensure that accounts are interoperable and able to be used for more than just receiving money. They can also build in customer choice about which accounts to use, as the Kenyan government and its development partners have successfully done since 2018. Programs can also team up with local partners to facilitate discussions to help couples negotiate financial decisions in the household.

Insight Three: Societal norms often dictate that women are caretakers of the home.

This leaves women with little time to do much else – including traveling to a DFS agent, which can be costly and time-consuming. This challenge is likely to be amplified during COVID-19. For instance, Halima, from Nigeria, got married as a third wife and has eight children. She walks her children to school every day and then heads back to do her house chores (fetching water, cooking and cleaning). She has no time in her day to do anything else, but she has dreams of running her own sewing business one day. She can’t imagine having enough time to leave the house for work, but would like to figure out how to operate the business out of her home.

How might we reduce the time and cost barriers of accessing their money for women like Halima? During COVID-19, women are likely to double down on their caretaker role, and their unpaid labor in the home will increase. In response, G2P programs should design systems that respect women’s time and are seamless and easy for them to use. The India Post Payments Bank, for example, has successfully piloted G2P program delivery through door-to-door postmen, who are also equipped to open digital accounts for recipients. If this sort of option isn’t available, disbursement points should be close to women’s homes, and G2P providers should consider staggering or spacing out payments so that women don’t have to wait for hours to get their money.

In the longer term, governments may consider relaxing agent regulations, as the accessibility of digital G2P programs often relies on recipients’ proximity to agent networks, and lack of mobility has been shown to significantly impact women’s financial inclusion.

Where we’re going next

Governments have an unprecedented opportunity to design gender-transformational solutions for low-income women while they are rapidly expanding G2P programs and disbursements in the context of COVID-19. By designing services and disbursements informed by what we already know about digital financial exclusion, these programs may be able to make the single biggest push for women’s economic empowerment that the world has ever seen. We encourage governments around the world to keep women at the forefront, and to design for their power.

Amanda Schwartz is a Senior Program Manager at IDEO.org.

Photos courtesy of IDEO.org.

- Categories

- Coronavirus, Finance