Scaling Access to Finance: Two Recent Studies Explore the Supply and Demand Sides of Funding ‘Missing Middle’ Enterprises in Emerging Markets

The World Bank estimates the financing gap for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in developing countries to be close to US $5.2 trillion. The lack of financing options is particularly problematic for the “missing middle” SMEs, i.e. enterprises that are too big for microfinance, but too small or too risky for banks or private equity firms. These enterprises, often also called small and growing businesses (SGBs), form the backbone of local economic growth and job creation in many communities. They provide access to essential goods and services to underserved populations, and spark innovative technologies and business models – but they have great difficulty securing the financial backing they need to grow.

While challenges are abundant for all missing middle enterprises, some segments face even bigger hurdles. A growing consensus has emerged that we need to better understand the supply and demand of finance for these businesses, to better serve their needs. To address this knowledge gap, two important publications have emerged over the last six months, addressing both sides of the financing equation.

Segmenting Small and Growing Businesses

A primary cause for the SGB financing gap is that small and/or early stage businesses are inherently hard to serve, due to complexities in understanding their risk-return profile, lack of information about their operations and other reasons. Another factor contributing to this persistent financing gap is the lack of an effective, widely adopted segmentation approach that could be applied to the highly heterogeneous universe of these businesses. To address this gap, late last year the Dutch Good Growth Fund (DGGF), Omidyar Network and the Collaborative for Frontier Finance, in partnership with Dalberg Advisors, released a report titled “The Missing Middles: Segmenting Enterprises to Better Understand Their Financial Needs.” (Note: Triple Jump and PwC manage the part of the DGGF that provides financing for local SMEs, and Triple Jump helped coordinate the research cited in this article.)

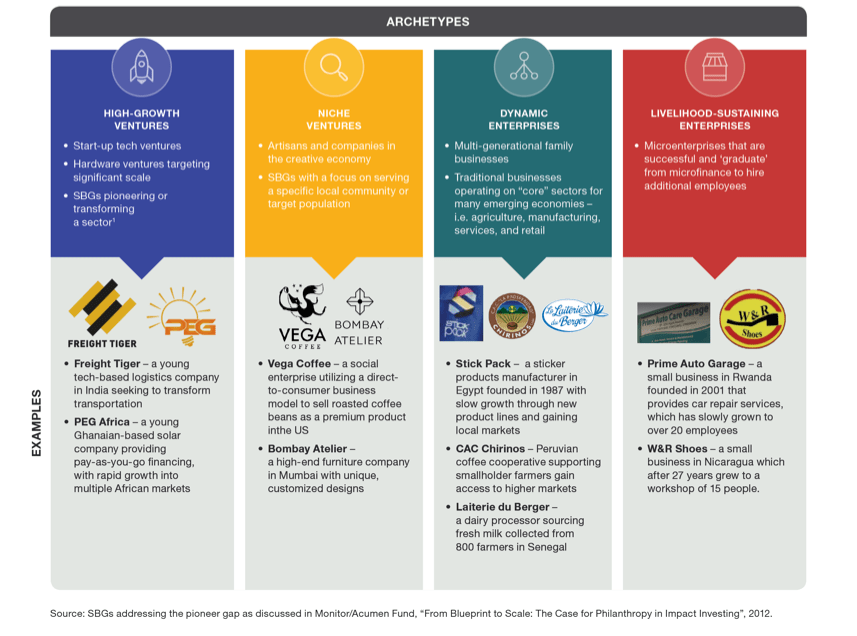

This report pioneers a segmentation framework that aims to help financial service providers, donors, investors and field-building organizations to better understand and navigate the complex landscape of SGB investment in emerging markets. The research sorts the whole global universe of SGBs with financing needs between $20,000 and $2 million into four distinct segments based on their needs and behavioral characteristics — which we called “families”:

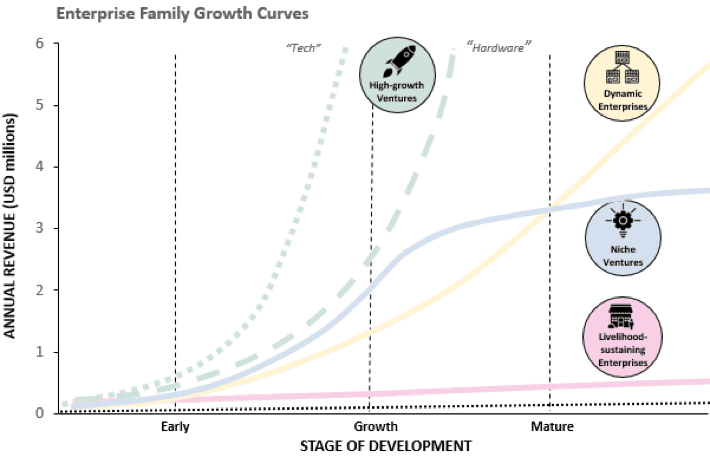

- High-Growth Ventures are distributive businesses targeting large and fast-growing addressable markets. These include scalable and growing businesses that pioneer new products, services and markets – typically tech-based startups in emerging markets.

- Niche Ventures are creative businesses focused on innovation and targeting niche markets. These entrepreneurs seek to grow, but typically prioritize other goals over massive scale, such as solving a social or environmental problem, serving a specific customer segment or community, or maintaining a product/service that is particularly unique in the market.

- Dynamic Enterprises are established medium-sized businesses in “bread and butter” industries (e.g. manufacturing, trading, retail) that seek incremental growth in local markets; and

- Livelihood-Sustaining Enterprises are opportunity-driven small replicative business models that are just able to survive above local inflation and are found in great number across the globe. These businesses often start out as “mom and pop” shops at the microenterprise level, but subsequently grow to hire additional employees.

Typical examples of businesses in each family are quite distinct, and they can be found across emerging markets (see figure below).

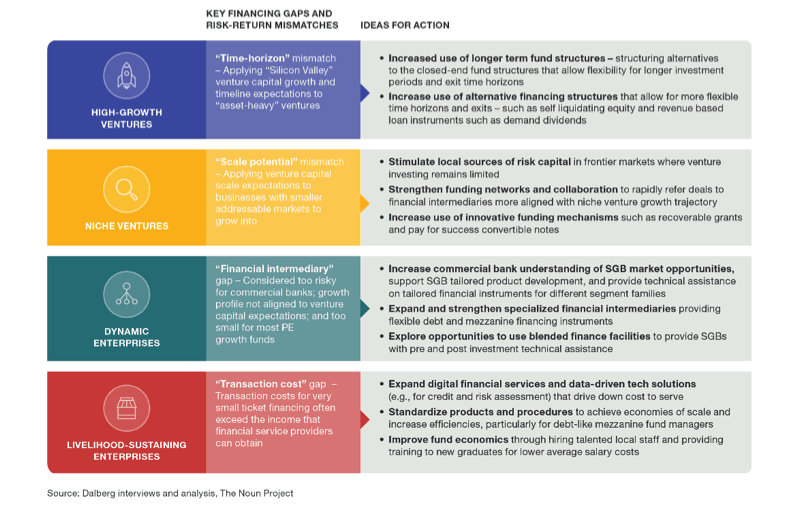

Looking at current SGB financing through the prism of the four enterprise families helped us to identify a roadmap for what we need to do in order to address the existing $930 billion SGB financing gap[1]. For each family we see clear financing gaps — but also clear examples of promising solutions being developed to address those gaps. The report highlights ideas for action (see the figure below) — many of which innovative investors and intermediaries are already advancing. We think it will be critical to implement and scale up these ideas, in order to unleash the potential of SGBs to drive economic growth and impact.

Scaling Access to Finance for Early-Stage Enterprises

The developed segmentation framework is helpful in getting insights on the types of mismatches and gaps in the whole universe of SGBs. But it doesn’t shed light on the types of financial instruments and financial service providers that can address these issues. In order to further advance our knowledge, in January 2019 the Dutch Good Growth Fund released its latest report, “Scaling Access to Finance for Early-Stage Enterprises in Emerging Markets: Lessons from the Field.” It focuses on the supply side of finance to one of the most underserved missing middle segments – the early-stage businesses, either in pre- or post-revenue stage, that have demonstrated traction in the market and potential to scale up, and that are seeking to raise $10,000 to $500,000. (These are typically High Growth or Niche Ventures, but may also be Dynamic Enterprises.) Early-stage finance is usually about providing a combination of working capital and capital expenditure financing, and often has to be non-asset based. New businesses are often perceived by finance providers as a particularly risky and challenging segment of the missing middle to serve, given their limited track record, high failure rates, low collateral and high transaction costs.

Hence, in this report we seek to explore how to improve the scalability and viability of early-stage finance provision, thereby reducing the need for philanthropic capital and subsidies among the local providers of finance and support to early-stage enterprises. We identified three main archetypes of early-stage finance providers to study in detail, namely: business accelerators, business angel networks and early-stage venture capital funds, together with broad category of supplemental, non-traditional debt options. Each of these four categories detailed in the report face challenges in providing finance to SGBs, and any investment approach needs to reflect the sophistication of local ecosystems and construct its funding modality accordingly.

There are three main lessons to be learned from this study:

- All early-stage finance archetypes can be refined and improved, by taking steps to become more effective and efficient, to use new income sources, and to establish smart, strategic partnerships – with the objective of reducing their dependency on subsidies and grants. Moreover, any financial intermediary needs to be constructed within the context of the ecosystem it operates in, rather than in isolation.

- Many promising hybrid models have emerged, strengthening interlinkages between different financial intermediaries. The report identified a number of interesting hybrids that deserve attention. One, Ibtikar Fund in the Palestinian territories, implements its investment strategy through partnerships with local accelerators in the West Bank and Gaza to initially nurture start-ups. The most promising companies receive increasing investments (up to US $1 million) from Ibtikar, together with hands-on non-financial support. Another promising model, Iungo Capital, engages with local business angels in Uganda through a co-investment structure, in which angels chip in with 5 to 10 percent of the invested amounts. The active involvement of local angels increases Iungo’s credibility, lowers transaction costs and provides access to a wealth of local knowledge. And angels can enter deals that are generally beyond their financial resources and diversification appetite.

- Investors, grant providers, governments and researchers have a critical role to play in the further development of the early-stage finance ecosystem. Early-stage finance providers and their supporters should engage in open conversations around small ticket sizes, actual risk, financial return expectations and impact potential. Obtaining accurate performance data and benchmarking is not easy, and more transparency will contribute to better insight into the performance of financial intermediaries. This will also help funders and intermediaries determine what type of patient and catalytic capital is required. In this sense, the current emphasis on blended finance – i.e. the strategic use of development finance and philanthropic funds to mobilize private capital – offers exciting opportunities.

Both reports discussed in this blog aim to shed more light on the challenges and opportunities of scaling access to finance for SGBs in developing countries, with the ultimate aim of stimulating economic growth and prosperity. DGGF’s early stage finance report is a first contribution to building a more robust understanding of early-stage enterprise finance. By stimulating constructive exchanges among finance providers and their funders and ecosystem partners, it hopes to encourage the emergence of a more sustainable and scalable approach to early-stage finance provision in emerging markets. Similarly, by proposing common language and terminology for different types of SGBs, the segmentation report aims to contribute to a better-functioning financing market that can generate more efficient matching between enterprises and financial service providers.

The number of financing initiatives focused on the missing middle is increasing, and institutional investors are looking to continue funding innovative business models. But the number of SGBs in these investors’ portfolios remains relatively small compared to the universe of businesses with unmet financing needs around the world. Thus further research, insights, collaborative efforts and ecosystem mapping are needed to deepen our understanding of how to develop and scale up both new and existing funding models.

[1] Based on the Collaborative for Frontier Finance’s analysis of the “MSME Finance Gap” (IFC 2017). This analysis focuses on the credit gap only in lower- and lower-middle-income countries and excludes microenterprises.

Karina Avakyan is a Knowledge Manager at Triple Jump.

Image provided by Village Capital.

- Categories

- Finance