Four Ways to Tackle Weak Competition in Digital Financial Services in Emerging Markets

Editor’s note: Throughout 2017, NextBillion is organizing content around a monthly theme, dedicating special attention to a specific sector alongside our broader coverage. This post is part of our focus on digital finance for the month of December.

Many developed digital financial services (DFS) markets in emerging economies feature problematic levels of consolidation. Policymakers are increasingly worried about the impact of dominant individual firms on financial inclusion and innovation, especially given the absence of robust competition policy. For example, in Kenya, Safaricom accounts for approximately 70 percent of mobile telecommunication subscribers and nearly 95 percent of the mobile money market. The Bangladeshi market for mobile financial services is similarly imbalanced, with one dominant firm (bKash) accounting for 55 percent market share and another, DBBL, accounting for an additional 38 percent, while the remaining competitors hold less than 1 percent of the market each. The situation is similar in Sri Lanka, where there is one dominant mobile money provider, Dialog, and its competitor, Mobitel, is much weaker.

In certain jurisdictions, these imbalances have resulted in a number of rulings and investigations into potential abuses of market power, including:

- Ezee Money’s successful lawsuit against the mobile network operator (MNO) MTN Uganda for denying it access to its USSD gateway in Uganda;

- Zoona’s continuing case against the MNO MTN Zambia for refusing it access to its USSD gateway in Zambia;

- Money transfer operator (MTO) Bitpesa’s failed lawsuit against Safaricom for refusing it API access to the M-PESA DFC platform in Kenya.

Similarly, in 2014, the Competition Authority of Kenya (CAK) ruled that Safaricom had to end agent exclusivity based on a complaint from Airtel. In 2016, the CAK investigated price transparency in mobile-related services and opened an investigation into whether lenders in Kenya deliberately withheld mobile credit data on good borrowers and only released information on bad borrowers. And in Zimbabwe, the Competition and Tariff Commission investigated excessive pricing and discriminatory access to USSD complaints and then mandated a significant reduction in mobile money transfer transaction costs.

These cases are motivated by a series of shared concerns among policymakers, regulators, financial inclusion advocates (and non-incumbent providers): that providers with dominant market power may abuse their position or form oligopolies with other players if not properly supervised; that innovation and inclusion will slow as a result of barriers to entry and the lack of interconnection and interoperability; and that downward pressure on pricing and incentives to innovate may stagnate without adequate competition.

Financial inclusion strategies may help prevent these types of abuses but, as The World Bank pointed out, such strategies are less likely in countries with relatively concentrated banking sectors and lower stock market capitalization: “These results may reflect the greater monopoly power and greater risk of regulatory capture in financial systems that are dominated by a handful of large banks. Financial inclusion strategies — which tend to call for greater competition among financial services providers — are likely to face stronger push-back in such concentrated systems.”

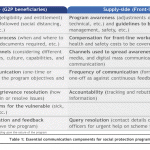

Beyond such strategies, we suggest four concrete ways policymakers and regulators can create and maintain a competitive playing field for all DFS providers, including banks, fintech firms, mobile money providers, payment system providers and others. Our recommendations seek to create pragmatic action points and tools to build institutional capacity while increasing our shared understanding of competition dynamics and the behavior of both service providers and users. These suggestions go beyond past work about weak competition policy and regulation in DFS by BFA and other partners, which has primarily taken place on a country-by-country basis from a diagnostic perspective. These prior efforts have highlighted an urgent need to develop industry-wide, globally relevant tools and guidelines for regulators and policymakers looking to address competition issues.

We suggest that financial authorities and their development partners should take the following steps:

Articulating Guiding Principles on Legal Frameworks for Competition in Emerging Countries’ DFS Markets

Problem: Competition policy has been formulated over the years in developed nations based on their specific political and economic objectives. These objectives may not be appropriate for emerging markets, and for the DFS ecosystem specifically.

Activity: Examine the different theories behind competition law – i.e., support for economic efficiency, consumer welfare or wealth redistribution – and the specific characteristics of DFS in emerging markets in order to identify which theories are the most appropriate to foster financial inclusion and innovation.

Output: Based on the above exercise, recommendations can be made on how:

- Competition policy can be formulated,

- Competition mandates can be structured, and

- Collaboration between different authorities can be designed and implemented to support the goals of financial inclusion and innovation.

Outcome: This exercise could result in a fundamental rethinking of the role of competition law and policy in countries where financial inclusion and innovation are key policy goals, by articulating high-level guiding principles for emerging market regulators who want to strengthen their competition legal frameworks.

Creating a Competition Diagnostic Toolkit

Problem: Many developed DFS markets feature problematic levels of consolidation and may not have the appropriate tools to address the abusive behavior that can result from such concentration.

Activity: Develop and test a diagnostic toolkit for policymakers and regulators to identify competition issues and assess whether the available policy interventions are adequate to address them.

Output: A toolkit that would allow policymakers and regulators to:

- Develop (and test) a set of criteria and indicators that (i) identify the variables that should be considered to decide if a DFS market is problematic from a competition perspective (i.e., is concentrated, has low barriers to entry, lack of technology and distribution channels available to all providers) and (ii) evaluate the impact that certain behaviors by market players may have on users (e.g., pricing structures, collusion, agent exclusivity);

- Understand which anti-competitive behaviors are common in DFS markets, and their impact on current and future market structures for specific DFS services and products;

- Assess the gaps in the current policy and regulatory framework; and

- Evaluate whether supervisors and regulators have implemented good practice with respect to the existing policy vision, regulatory framework and institutional capacity.

The toolkit should be dynamic in the sense that it should easily adapt to different typologies of DFS markets, i.e., those dominated by banks, those dominated by non-banks, those that include fintech firms, those where platforms such as Facebook are active, etc.

Outcome: Ultimately, by helping countries assess the market dynamics at play and the available policy and regulatory remedies to create and maintain competition, this framework would create a roadmap for ensuring a level playing field in the DFS ecosystem to support financial inclusion and innovation.

Supporting Competition-Focused Regulation Technology (Regtech) and Open Data

Problem: Competition, telecommunication and financial authorities lack the necessary data and tools for analysts to fully understand market dynamics.

Activity: Enhance the capacity of authorities by using and creating competition–focused regtech solutions.

Output: A regtech solution that would:

- Identify indicators for monitoring competition; and

- Extract, analyze and help interpret meaningful supply-side and demand-side data to inform supervisory and regulatory work.

Outcome: This regtech solution would equip the authorities with the data and tools to make informed decisions about whether to launch competition enquiries, alert other agencies of market abuses, amend existing regulations, or design incentives targeted at specific types of firms. Moreover, the authorities may use part of the data to develop and share high-quality open datasets in the public domain to boost the development of new products and business models.

BFA’s implementation of the RegTech for Regulators Accelerator (R2A) in Ghana, Mexico and the Philippines, and its data-stack work in Nigeria show that this type of solution is already in high demand.

Examining Competition Issues Raised by Control Over Customer Data

Problem: Until recently, the exchange of personal data for a “free” service such as internet searches or social media was considered to have no effect on the market, given the lack of exchange of value in the traditional sense. However, policymakers and regulators are now questioning how the extraction and use of data that users generate online and over other platforms (e.g., using mobile money) may impact competition. The nature of these data-based business models is challenging, and the current tools available to policymakers and regulators to monitor these markets and prevent misuse of these data are inadequate.

Anti-competitive practices with respect to the sharing of data on customer creditworthiness also impact financial inclusion and innovation. For instance, the selective dissemination of creditworthiness data may disadvantage certain market players, as was the case in Kenya where the Central Bank of Kenya in 2016 accused lenders of failing to submit accurate and complete data to the credit bureau.

Activity: Undertake specific research on competition issues and customer data, focusing on:

- How higher-income countries are currently dealing with competition issues raised by big data in general;

- How developed countries are proactively legislating to protect such data and foster competition in financial services in particular (e.g., open banking and the EU Second Payment Services Directive); and

- Specific emerging-market innovations such as the Digital Locker in India and the mandatory open banking API in Mexico (a provision for which is included in the country’s draft Fintech Law).

Output: Research that offers original ideas on how emerging markets can “leapfrog” higher-income nations to ensure the adequate protection of data while exploiting its capacities for positive impact.

Outcome: This work could result in a set of best practices for the regulation of big data in DFS that would take into consideration the specific characteristics of emerging markets, and develop recommendations on regulatory tools for competition, supervision and data protection.

Conclusion

As market concentration in DFS is creating imbalances in many emerging economies, there is an increasing urgency to develop industry-wide, globally relevant tools and guidelines for regulators and policymakers to create and maintain a competitive playing field for all DFS providers. This should be done hand-in-hand with current country-focused work, in order to both shape this work and to draw more long-term lessons for competition and sector-based policy work on a global scale.

Simone di Castri is director of policy and ecosystem development at BFA.

Ariadne Plaitakis is a senior associate of policy and ecosystem development at BFA.

Photo by Kat Northern Lights Man via Flickr.

- Categories

- Finance, Technology