From Trash to Resource: How Technology Can Help Informal Waste Pickers Solve India’s Recycling Problem

India generates up to 62 million metric tons of waste every year. Ninety-one percent of this waste – including recyclable plastics, paper, glass, wood and metal – makes its way through a largely inefficient waste management infrastructure to landfills in the fast-gentrifying suburbs. Kabadiwalla Connect (KC), a technology-based social enterprise based in Chennai, has determined that leveraging the informal ecosystem of urban waste recyclers has the potential to decrease by 70 percent the amount of waste sent to landfills. They aim to do just that with their end-to-end technology platform that leverages the extant, albeit informal ecosystem of waste collectors, aggregators and recyclers by making them more accessible to small and medium waste generators, and to government and private enterprises which have the capabilities to process and recycle the waste.

With uncontrolled urbanisation and rising city populations, urban waste management in India has always been a complex problem to solve, despite repeated efforts by municipalities and NGOs. The country’s growing number of landfills, which are often poorly managed, pose a rising threat to the environment. Chennai’s largest landfill, located in Pallikaranai, has long been the subject of concern owing to its role in the depletion of the Pallikaranai marshlands, contamination of groundwater, health hazards and reduced quality of life posed to those living in its vicinity.

At the same time, waste generated in cities presents an opportunity for private-sector investment. According to market research, the waste management market in India will be worth US $13.62 billion by 2025, with an annual growth rate of 7.17 percent. While local governments and private enterprise in the developed world have been successfully converting waste to resource over the past decade, markets in India and other developing countries with similar economic and social indicators have been far tougher to crack, especially with respect to small and medium waste generators.

“While buying from bulk waste generators like factories or industrial establishments that generate enough waste consistently makes financial sense to middlemen and social enterprise, it does not amount to much at an aggregate level. About 68 percent of the waste generated in Chennai, for example, is post-consumer waste from households – but it is generated in smaller disaggregated units,” says Siddharth Hande, founder and CEO of KC. “In cities in Europe and North America, household waste is segregated at the source and recovered through curbside collection so that only the stuff that has zero value goes into the landfill. Such a system doesn’t exist in Indian cities.”

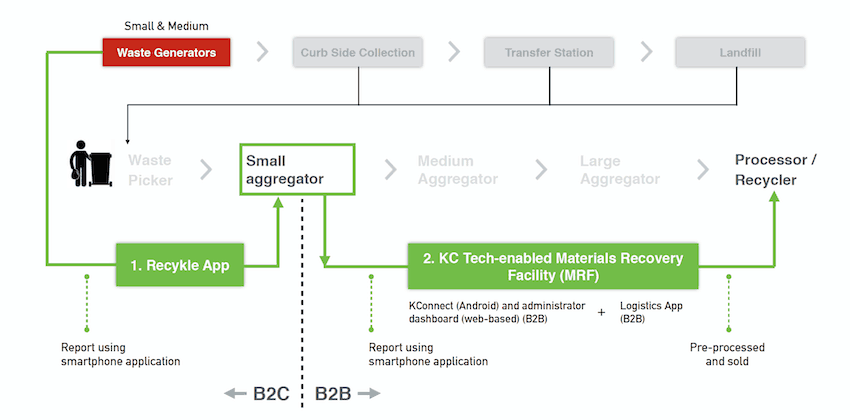

What Indian cities do have is an informal network of waste pickers – small, medium and large aggregators, processors and recyclers whose livelihood involves converting waste to resource. Here’s how it works: The waste picker or itinerant buyer goes around a neighbourhood by foot or cycle-rickshaw, respectively, and collects recyclable waste from households and small enterprises. They sell the waste to small aggregators, or “kabadiwallas,” who trade from small shops (typically about 4×4 feet) where they segregate and store the material until they sell to middlemen who own larger warehouses. Once the middlemen have aggregated a sizeable volume, it is sold to processors who sell it back to industry.

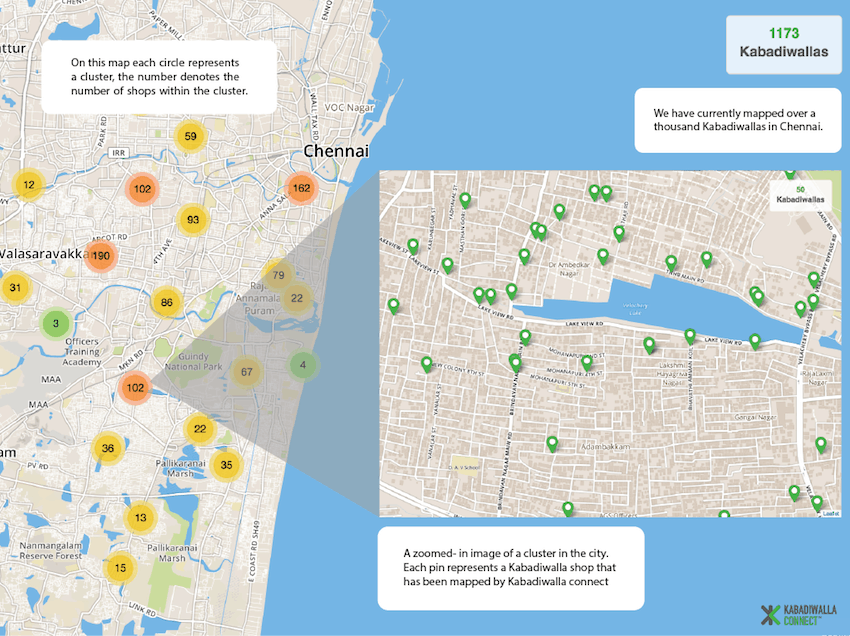

In 2015, KC used funding from a World Economic Forum grant to conduct research into the small aggregators – the kabadiwallas of Chennai – and arrived at three key findings. First, kabadiwallas were ubiquitous throughout the city; they mapped close to 2,000 in Chennai (see the chart below). Second, kabadiwallas already source back 33 percent of the total recyclable waste in Chennai, which includes paper, plastic, glass and metal. Third, and significant for KC’s intervention, 30 percent of kabadiwallas owned and operated a smartphone. Additionally, KC also found that kabadiwallas were hindered by a lack of visibility, lack of formal integration and information asymmetry.

While most households are familiar with the concept of the kabadiwalla, they can be hard to find in some localities. Relatively small volume and a lack of formal agreement with processors meant that they have to sell to highly exploitative middlemen who buy at a 20 percent margin and sell to processors at exorbitant margins of 300-400 percent. A gap in knowledge about material or prices often led to more exploitation or missed opportunities. For example, plastic is a high-value material but its volatile price and many different grades presented pricing and segregation issues that hindered trade.

End-to-end solutions for waste reduction

The KC technology platform seeks to address these issues from both ends. Their business-to-consumer app, Recykle, helps households to connect with local kabadiwallas, channeling waste from households directly to the kabadiwalla, partially solving the problem of visibility. KC also facilitates this process by providing resources for users, and answering any questions that they may have through the app itself.

Also, KC’s business-to-business platform includes a survey app to connect to bigger buyers, a logistics platform and a dashboard that can potentially be used by municipalities, management companies, residences and corporations to efficiently manage their waste at all stages. The company is also working on an IoT “smart bin” that will use optical sensors and real-time reporting to improve the logistics of waste collection.

In addition to their technology platform, KC is also playing the role of processor by running their own material recovery facility (MRF), where they are currently experimenting with their platform, making moderate but rising profits. The platform can also be adapted to manage waste in other developing economies (see the chart below).

Juxtaposing this technology onto the existing informal ecosystem means that households can now contact kabadiwallas via the platform, which in turn allows the kabadiwallas to directly contact the processor – now limited to KC – who buys the material. KC’s disruption is in their technology. Hande explains: “In any procurement game, volume is king. The more volume you aggregate, the higher the value and better price you command. Traditionally, the middlemen own warehouses in which they can collect and store large quantities, allowing them to sell at high margins. KC’s virtual storehouse enables small kabadiwallas to virtually combine their stocks and function as a selling club, thus cutting out the middleman and getting a better price for everyone.”

KC’s MRF has sold about 115 tons of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) – plastic commonly used for water bottles – over the course of six months and has made about US $60,000 in revenue, with a 20 percent profit margin, making a convincing case for their model of waste management. The company is currently in the process of raising US $500,000 to set up India’s first machine-run plastic recovery facility that can handle all the grades of plastic that are commonly collected in Indian cities.

Rethinking informality

Most research on the informal ecosystem of waste has focussed on the waste picker and been largely ethnographic in nature. It’s here that KC’s approach diverges from the conventional. Rather than approaching the informality as a problem and developing a new system for waste management, KC uses their technology platform to leverage the already existing informal infrastructure toward a more efficient waste management system.

This means buying and selling at fair prices, conducting research to fill information gaps and also nudging kabadiwallas to do things that improve the working conditions of the waste pickers, like providing them gloves.

However, embedding technology into an ecosystem characterised by information asymmetry is not easy, and conducting business in it is a decidedly precarious task. “Most kabadiwallas were very open to speaking with us during our initial research but it was tricky to ask about price; most of the figures they gave us were inflated. This is because of a huge asymmetry of information, which also means that a person who is looking to set up a processing plant has no information from which he can draw projections for his business,” recalls Hande.

Though much of the system still demands investigation, the KC platform has made the informal ecosystem more accessible to other players. Municipalities can synchronise and start selling to the informal sector; waste management firms can source from it; corporations can carry out their extended producer responsibility through it; apartments and small businesses can send their recyclable waste directly to kabadiwallas that are part of it.

According to a post on the KC blog, informal waste economies have existed since the 19th century, and were common in Europe where rapid urbanisation and industrialisation meant high quantities of waste, as well as a rise in the demand for raw material, which was cheaper when sourced from waste. Waste management systems in these countries were, however, soon completely formalised and managed by local governments. The opposite is true for developing countries like India, where informality persists and a rising number of unskilled migrant workers in cities earn their livelihoods through informal occupations in the waste economy.

With Kabadiwalla Connect, Hande hopes to provoke thought into how informalities are viewed and tackled by governments and policymakers. “The IMF recommends that rather than removing the binary of formal and informal, you need to work with them and push them to be more equitable, and ICT can play a big role in that,” he said. “In this regard, the learnings from KC can actually be extended to other OECD countries where over 60 percent of the workforce is employed by the informal economy.”

Zeenab Aneez is an independent journalist and researcher who writes about technology, gender and life and livelihood in Indian cities.

- Categories

- Environment, Social Enterprise, Technology, WASH