When ‘Wonder Drugs’ Aren’t Enough: Viral hepatitis reaches watershed moment, but who will pay?

It’s not every day that a cure is found for a deadly disease affecting millions of people. Yet that’s what happened with the recent introduction of new medicines that can cure hepatitis C, an often-fatal virus which destroys the liver. Now, as little as a single tablet, taken once per day for eight-12 weeks and with significantly fewer complications than from other existing therapies, will cure more than 90 percent of the cases of this form of the disease, potentially saving millions of lives and avoiding costly treatment and often deaths from liver failure, and reducing spread of the disease. Surely this is a watershed moment for this silent killer. But at what cost? Who will pay?

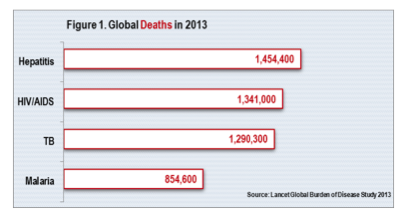

With the decline in deaths from HIV and AIDS, viral hepatitis is now the seventh leading cause of death worldwide (1.45 million per year), surpassing the number of deaths now attributable to HIV and AIDS or malaria or tuberculosis, according to the World Hepatitis Alliance and the World Health Organization (Figure 1). Viral hepatitis kills 4,000 people per day and causes 75-80 percent of all liver cancer. Worldwide, as many as 400 million people are living with hepatitis B or C. Hepatitis C on its own affects approximately 2-3 percent of the world’s population. And of the 36 million people living with HIV and AIDS, it is estimated that 1 in 4 is co-infected with hepatitis B or C.

Viral Hepatitis is Complex

Yet this major killer is not well understood by the public. People may know that hepatitis affects the liver and can be deadly, but little else. One reason is that viral hepatitis is a complex disease, caused by five different types of the virus (known as hepatitis A, B, C, D and E). To make matters more complicated, different variations, called genotypes, exist within a single virus, affecting how successfully patients will respond to treatment. And each type of viral hepatitis exhibits different behavior along a number of parameters, including how the virus is transmitted (e.g. via contaminated food or water in the case of hepatitis A and E, or via blood or other bodily fluids or from mother to child in the case of hepatitis B, C and D); the incubation period of the virus (before symptoms appear); morbidity and mortality; whether it is vaccine preventable; and treatment modalities.

Yet this major killer is not well understood by the public. People may know that hepatitis affects the liver and can be deadly, but little else. One reason is that viral hepatitis is a complex disease, caused by five different types of the virus (known as hepatitis A, B, C, D and E). To make matters more complicated, different variations, called genotypes, exist within a single virus, affecting how successfully patients will respond to treatment. And each type of viral hepatitis exhibits different behavior along a number of parameters, including how the virus is transmitted (e.g. via contaminated food or water in the case of hepatitis A and E, or via blood or other bodily fluids or from mother to child in the case of hepatitis B, C and D); the incubation period of the virus (before symptoms appear); morbidity and mortality; whether it is vaccine preventable; and treatment modalities.

Another reason is that the disease burden of viral hepatitis varies dramatically across countries and population groups. Although the reality is that everybody is at some risk of the disease, hepatitis B and C disproportionately affect marginalized populations, including people who inject drugs and people who are living with HIV and AIDS, creating a stigma for the disease.

Hepatitis C Breakthroughs – Exciting But Costly

New “wonder drugs” (called direct-acting antiviral drugs, or DAAs) are available for treatment of hepatitis C, which affects 130 million to 170 million people and is 10 times more infectious than HIV. Gilead’s Harvoni costs as much as $1,000 per pill, translating into approximately $80,000-$90,000 per treatment. Pharmaceutical suppliers, clinicians, patients and others argue that such treatments, although costly, are a better buy and have better health outcomes than a liver transplant for end-stage liver disease, which in the U.S. can cost nearly four times more ($300,000).

Access to Medicines: What is Equitable?

Pharmaceutical manufacturers are racing to license breakthrough medicines for hepatitis and offer tiered pricing based on a country’s economic status to increase access (and expand markets) to these drugs in low- and middle-income countries. But it is not without controversy. These initiatives create huge, hard-to-justify pricing differentials across countries and still-out-of-reach prices for most people even where costs are at their lowest (e.g., $900 per course of treatment in Egypt).

Patient assistance programs, which enable purchase of branded medicines at a discount, can also provide real relief to clients who must pay out-of-pocket. At the same time, such discounts, when offered to insured clients in the form of waived co-payments or deductibles, can override financial incentives to use more cost-effective medicines covered under insurance programs sponsored by governments, private insurers or employers, increasing the costs borne by these payers.

Most of all, debate rages about what constitutes fair pricing practices for a lifesaving drug that could save millions of people – and how to balance affordability and access with sustained investment in R&D, company profits and responsiveness to stakeholders including patients, health care providers, payers and shareholders.

Viral Hepatitis – Mysteriously Absent

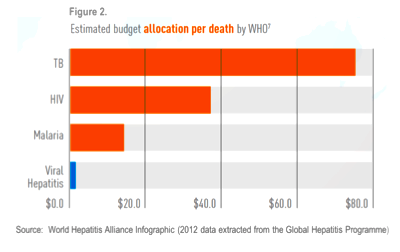

Despite these statistics and major developments, viral hepatitis fails to achieve equal footing on the global health agenda. Compared to other infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and HIV, it receives a fraction of the available funding and program support (Figure 2). Only a third of countries have written plans to eradicate hepatitis; even with one in place, implementation often falls short.

All countries face the intractable dilemma of how to allocate finite resources for health care, including prevention, diagnosis and treatment of hepatitis. Rationing may be done explicitly through lists of included or excluded services, or implicitly based on what services are actually available and accessible to patients. Hepatitis services may be covered under public and private insurance programs, but new and costly drugs may be excluded or simply unavailable, effectively limiting access to needed treatment. Negotiations, at the country and donor level, to allocate resources for hepatitis require sustained visibility and commitment, achieved through continuous dialogue and engagement of stakeholders.

Now is the Time

Today, July 28, marks World Hepatitis Day, first recognized in May 2014 by the World Health Assembly when it adopted a resolution to improve prevention, diagnosis and treatment of viral hepatitis. This global campaign presents an ideal moment to advocate for increased public awareness of the massive human and economic consequences of hepatitis, and how it can be prevented and treated – and ultimately eradicated.

Today, July 28, marks World Hepatitis Day, first recognized in May 2014 by the World Health Assembly when it adopted a resolution to improve prevention, diagnosis and treatment of viral hepatitis. This global campaign presents an ideal moment to advocate for increased public awareness of the massive human and economic consequences of hepatitis, and how it can be prevented and treated – and ultimately eradicated.

The United Nations General Assembly is preparing to finalize and adopt the post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which will supersede the Millennium Development Goals. The stated goal for health in the SDGs is to “Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.” One of the targets under this goal mentions viral hepatitis. Another target focuses on attainment of universal health coverage, so that everybody can access the health care they need (including hepatitis prevention, diagnosis and treatment) without financial hardship. As momentum builds under the emerging SDG framework, there is no better time for hepatitis to take its rightful place on the global health stage, with a better-informed public in full support.

Jeanna Holtz is a principal associate, International Health Division, with Abt Associates. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author and do not reflect those of Abt Associates.

- Categories

- Health Care