Impact Investing Has it Backward: It’s Time to Prioritize the Needs of Social Enterprises, Not Just Investors

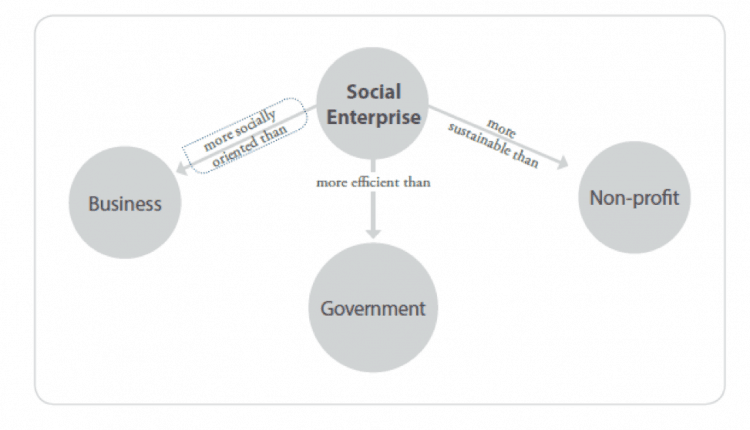

Social enterprises are unique additions to our economic landscape. While they employ business principles to earn revenue and offset costs, their primary mission is to create positive social and/or environmental benefits. They often work in challenging business environments where the need for balancing social objectives with financial sustainability is paramount. However, the capital they depend on expects a lot from them: On the one hand, they should be more efficient than governments, and on the other hand, more sustainable than the nonprofit sector, while simultaneously being more socially conscious and even as profitable as traditional business. The truth is that the impact investing story has not been told from the social enterprises’ perspective and so the field remains blissfully unaware – or intentionally ignorant – of the social enterprises’ experience as they seek and gain impact investments, which often involves accepting financial terms and/or partners that can distract from their social mission.

From SELCO’s 2015 article, “Bridging Gaps: Impact Investors and Social Energy Enterprises”

For the field to evolve, we need to start telling – and hearing – their stories. To that end, we offer the financing story of the two-decade-old social energy enterprise, SELCO India. Since 1995, SELCO has delivered solar-based energy solutions to low-income communities in a financially and socially sustainable manner. SELCO’s is a deeply client-centered approach. For example, it adopted the role of systems integrator, which means it does not manufacture components itself, but rather establishes partnerships with local suppliers for component parts like panels, batteries and electronics. By leveraging this portfolio of partners, it is able to tailor energy solutions specifically to the needs of each particular client. Understanding the mobility constraints of rural clients, SELCO has achieved its reach through 52 energy service centers across five states in India and employs over 375 local sales and service staff to support its customers. It has also built partnerships with local financial institutions to provide user-centric financing via a cash flow lending approach.

SELCO understood how grant dependency could threaten its financial sustainability and, as such, rather than registering as nonprofit, it registered as an Indian private limited company in 1994. Early expansion was funded by a conditional loan from USAID and equity from E+CO and SELCO USA. After seven years, SELCO broke even, and after 11 years, it had peak profits of $88,380 USD. In 2003, further expansion was supported by a low-interest IFC loan.

The trouble started in 2006, when demand in the German solar market spiked and Indian panel manufacturers began mass production and export of high wattage panels, neglecting production of smaller panels. This led to an inventory crunch for the types of smaller panels SELCO sold to its low-income clients and significantly increased their costs. As a result, SELCO came under significant pressure from primary investors at SELCO USA to cut back on workforce and focus on larger system orders to bolster profits. This was in direct conflict with the philosophy of the organization and would have spelled doom in the future, both from a business and social impact standpoint. SELCO believed maintaining its intellectual capital was vital and focusing on larger systems was unsustainable for fulfilling its social mission.

SELCO was able to access the social finance field outside of India and, thus, able to attract capital that understood the importance of maintaining the clean and affordable energy network that SELCO had built. With the help of the IFC and E+CO, SELCO refinanced the business, which included taking out SELCO USA and replacing it with long-term social investors, including E+CO, Lemelson Foundation and Good Energies Foundation in 2007. In its fundraising pitch, SELCO focused on its measurable social returns and projected only modest financial returns. These were investments not grants yet the primary performance criteria were social with a focus on financial sustainability. This gave flexibility to SELCO’s management team to make strategic decisions that were optimal from a social standpoint but could have been seen as too costly or time-consuming if profit maximization was the primary measure of success.

For example, rather than focusing exclusively on sales growth, SELCO took pains to cultivate a financial network that would allow its clients to access appropriate financing. SELCO understood that its target clients would be unable to afford outright purchase of solar systems but with the right type of financing would make excellent borrowers. However, SELCO did not want to become a lender itself. Instead, it set about improving the ecosystem through partnerships with local financing institutions with deep rural reach, persuading them to offer cash-flow based lending. This required educating banks on the benefits of financing clean energy systems for low-resource households, a technology and client base that was still new to many. SELCO raised some grant funds to provide partial guarantees to banks to de-risk their entry into the space of energy financing for people living in poverty. This extra effort took time away from its core activity of selling energy systems but was seen as an important aspect for the sector to be built in a pro-poor manner. Despite this “impact first” orientation (or perhaps because of it), SELCO has grown to over US $6 million in revenue with 375 employees earning a self-sustaining 2 percent return.

SELCO’s experience is emblematic of so many other social enterprises that prioritize social returns within fragmented enabling environments. Its experience points to several improvements that the impact investing field should consider:

- Fund Zebras not Unicorns: “Unicorns” are the typical high-growth VC target companies that grow exponentially and carry the returns for an entire VC portfolio. An alternative concept that has been offered recently is “zebras” – normal growth businesses that “balance profit and purpose, champion democracy, and put a premium on sharing power and resources.” SELCO knew it was a zebra and that this limited the pool of possible financial partners. Managers steered clear of investors who they felt could lead the firm to “mission drift,” wherein the values upon which the social enterprise was founded become negotiable. Even with mission-aligned investors (or perhaps thanks to them), SELCO has built mission protection safeguards such as staff incentives for those going the extra mile to achieve impact, and checks and balances in its governance practices to avoid decisions that would move SELCO from its original vision and mission.

- Set the right notions on internal rate of return: Zebras will not achieve unicorn-status –like IRRs. Zebra firms reinvest not exclusively in their businesses but also in the communities around them. For SELCO, responsibly selling decentralized renewable energy systems among poor communities and households has required considerable financial and human resources to build a functioning system with appropriate financial products, market linkages, robust after-sales service and new products co-developed with people living in poverty. This extra effort has resulted in IRRs and profits in the single digits, however, this is not by accident as much as by design. While SELCO’s investors have received less than they could have from many traditional investments – and far less than from unicorn funds, which according to the Kauffman foundation often fail to exceed returns available from the public markets – this intentionality around impact has meant that the community has received considerably more.

- Dig beneath the surface: Common metrics of success focus on growth. In the absence of strong oversight, mission-supporting safeguards and transparency, this can result in a dangerous tendency to pursue large volumes over developing responsible processes. We know this from the history of microfinance where, in certain circumstances, the social mission was subjugated to the pursuit of sales targets. At SELCO, a branch that outperforms its peers in terms of revenue growth may not be succeeding in delivering its impact goals, since selling just a few solar systems to large institutional buyers can lead to high revenues, while selling smaller systems in more remote regions is considerably more time-consuming. SELCO rewards its staff accordingly by aligning performance incentives and recognition around impact achieved – for instance, when a staff member figured out that Indian dairy farmers would directly benefit if more dairy co-ops had access to reliable energy. The staff member understood the problem that many dairy farmers faced, ie., that they would waste time traveling to their co-ops only to find that, because they had no electricity, the co-op was unable to weigh and price the milk. The solution was a market-based one: to work with dairy co-ops to solarize their systems.

In impact investing, we have the opportunity to rethink the rules, incentives and structures of money lending that have defined traditional finance. Investors in this space and the funds in which they invest should act in service of the greater goals they are collectively looking to achieve: poverty alleviation, gender justice, energy access, etc. Hence, the rules, mechanisms and structures, not to mention attitudes and behaviors of impact investors, should adapt to be first in service of those goals, and second, in service of the enterprises and stakeholders who will help achieve those goals. The first step is to listen.

Mara Bolis is a senior advisor at Oxfam, where she leads work on shareholder advocacy, as well as influencing work on impact investing.

Sarah Alexander is a senior advisor at SELCO, which seeks to develop enabling conditions for the replication and scale-up of energy access solutions for the poor.

Photo by Georg Birkert @elektriker on Unsplash.

- Categories

- Impact Assessment, Investing, Social Enterprise