Clean Cooking is Heading for Failure: Why the Sector Needs a Real Strategy – Not Just a List of Ideas

The clean cooking sector needs help. The smoke and particles emitted by inefficient, dirty cooking fuels affect 3.83 billion people in 71 countries and kill over four million people annually — mostly women. The social and environmental cost of continued inaction reaches trillions of dollars annually. Yet even well before the pandemic, progress toward addressing this long-standing global crisis had stalled, and it was clear that business-as-usual was insignificant when compared to the scale of the problem.

The key stakeholders in the sector know all this, as do the governments, donors and financial institutions that support their work. But instead of significantly altering their approach, they’ve tried to get by on slivers of good news, soft commitments and get-togethers.

However, recent developments suggest that this may be changing. For more than a year the Clean Cooking Alliance (CCA), arguably the most influential NGO in the sector, and the global consulting firm Dalberg have been leading an effort to formulate a “Systems Strategy” for the entire clean cooking ecosystem. To that end, they have conducted interviews and gathered insights and recommendations, which they’ve summarized and presented as a set of principles, pathways and enablers. Based on this research, they’ve proposed 19 possible initiatives, with three called out as early action items (a Results-Based Finance (RBF) Accelerator, Delivery Units Network and User Insights Lab). They’ve announced that the final phase of this process will consist of co-creating and launching specific initiatives with other interested collaborators.

The CCA-Dalberg effort represents a formidable body of work — it’s recommended reading for anyone who wishes to climb the cooking sector learning curve. Unfortunately, it is not the ecosystem-wide strategy that is badly needed, and it won’t change the sector’s current trajectory which, make no mistake, is going to end in failure. The article below explores where the current strategy goes wrong and proposes a better way forward.

Strategy vs. Tactics vs. Goals

A strategy presumes a clear-cut goal and presents a plan to reach that goal. To create that plan, it’s necessary to articulate and analyze the crucial hurdles to reaching that goal, setting aside lesser objectives that may also appear important and interesting so that the essential goal can be prioritized. Tactics are the activities and ideas that contribute to executing the strategy and reaching that goal. Strategy is the “what” of a plan and tactics represent the “how” — both in service of achieving the key goal.

What then is the goal for the clean cooking sector? Is it to:

- Eliminate traditional, “dirty” cooking methods (Tier 0 and 1 of a multi-tier measurement framework)?

- Enable modern cooking (Tiers 4 and 5) for all?

- Grow the existing sector’s human, financial and institutional infrastructure?

- Align so-called adjacent sectors (e.g., public health, electrification, gender) with clean cooking, and leverage their infrastructures?

- Put cooking on the climate agenda?

- Make cooking a public health or human rights issue?

- Create a “Clean Cooking Finance Campaign,” a “User Insight Lab,” an “Ethanol and Advanced Biomass Agenda,” an “RBF Accelerator” or a “Clean Cooking for Climate Campaign”?

- Or, in Sustainable Development Goal-speak, “Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all” (as measured by the proportion of the population with primary reliance on non-solid cooking fuels)?

Within the CCA-Dalberg work to date, you will find versions of each of the preceding goals, to the point that you might wonder if their approach is merely to put something forward to please every one of the sector’s many stakeholders. (In all fairness, CCA does hedge its responsibility for “creating” this strategy by assigning “co-creating” responsibility to everyone participating, and this may explain why the result is inevitably a menu not a strategy.)

But goal setting matters. So does differentiating among potential goals to determine the most essential ones, while distinguishing between goals and tactics. Otherwise, focus is lost and resources cannot be concentrated. The sector needs a coherent strategy and a clear statement of what will be emphasized and what will not, supported by an argument for the pros, cons and course corrections implicit in establishing these priorities.

The Basis for a Clearer Plan

Fortunately, the current strategy proposal contains the seeds for a more targeted approach. If you examine the pertinent CCA-Dalberg documents for hints of their core strategic elements, you will find three very powerful ones:

- Country self-determination should be the focus, rather than a one-size-fits-all approach to determining the appropriate technology, fuels, type of project or financing.

- Everyone should be the beneficiaries, instead of focusing on just rural or urban populations, or on communities that are able to pay (or are too poor to pay).

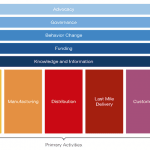

- Systems approaches must be taken, including not just end-users but also last-mile delivery enterprises, producers, fuel entrepreneurs — the entire value chain.

A strategist such as Dalberg can work with those three points. For example, if their work with CCA to-date had concluded that a country-by-country system assessment should be conducted as a precursor to eradicating energy poverty for all, then these three criteria could be met through that process. But sadly, that’s not the conclusion they put forth. Alternatively, if countries were asked to prepare the equivalent of Nationally Determined Contributions for clean cooking, as the Paris Agreement did for climate change, then these three strategic criteria could be the subsequent focus. But you won’t find that conclusion among the 19-part menu of the current strategy (though CCA leadership has tried to suggest it in subsequent press coverage). As it is, the three core action items on the CCA-Dalberg list (RBF Accelerator, Delivery Units Network and User Insights Lab) do not touch on these strategic points.

Of course, there are different ways to work with these strategic elements, which leads to a question for CCA and Dalberg: Under the current strategy proposal, exactly how will countries self-determine what they wish to do, in order to eradicate what they define as cooking poverty and improve their in-country ecosystems to reach all the people who suffer from it?

A further question: How does the current strategy react to its own insight that donors and investors are inappropriately focusing their efforts on low-hanging, bright and shiny fruit (such as different high-priced stoves or novel payment systems)? Does it recommend that donors instead support the creation of 10, 20, or 71 country-level assessments, holistic systems-based interventions and implementation plans that reflect what can realistically be done to improve those systems? No. The work to date simply proposes a shopping list of initiatives and avoids making anything that could reasonably pass muster as a coherent, sector-wide strategy.

Three Potential Strategies for Clean Cooking

But despite the shortcomings of the current strategy, it is not too late. Here are three distinct options for alternative approaches, featuring goals, strategies and tactics that could be stated clearly and executed transparently.

Option 1: Business as Usual

- Goal: to continue with the sector’s current approach and add a few initiatives

- Strategy: to assess and validate the effectiveness of existing and newly envisioned activities

- Tactics: Define the sector narrowly to avoid the complexity of coordinating with related development efforts (like electrification and public health); gather ideas from these key sector stakeholders; create a framework of pathways and values; distill these elements into a long list of initiatives — then refine it into a short list; invite defined sector stakeholders to critique and be involved in these initiatives; make announcements and publish opinion pieces raising public awareness of them.

- Benefits and costs: This option would maintain the status quo institutionally and would require little adjustment of the current approach. It may add incremental resources to the sector. But it wouldn’t solve the existing multi-trillion-dollar annual cost of inaction. And it wouldn’t provide needed solutions that are compatible with the scale of the problem.

- Comment: This approach would not change the ad hoc nature of the sector. It would allow for the continued opportunistic and incremental expansion of activities, which may be all that is possible.

Option 2: Scale-up Improvements

- Goal: to eradicate energy poverty for 3.83 billion people in 71 countries

- Strategy: to empower countries to eliminate cooking poverty by bridging to the larger goal of eliminating energy poverty (including both cooking and electricity) by advancing electrification, bundled with improved and modern cooking

- Tactics: Individual countries set goals, engage consumers and stakeholders, define what they consider “eradicating cooking poverty” to mean, and map their own national ecosystems. The international community embraces these nationally determined goals country-by-country; essential gaps in each country’s ecosystems are identified, and multi-year commitments are made to fill these. The implementation of these efforts is designed to align all country institutions working toward SDG 7 (including energy access, decarbonization and energy efficiency).

- Benefits and costs: It would cost $100 billion for all countries to reach Tier 3, and $1.5 trillion for all to reach Tier 4 and 5. This approach would require the expansion of country-level infrastructure — to that end, one recommendation would be to align these efforts with electrification and tap directly into the green finance wave. It would facilitate step-by-step progress in reducing the drudgery and risk inherent to traditional cooking, creating opportunity and perhaps avoiding serious disease — and certainly reducing discomfort and preserving natural resources.

- Comment: This option would enable modern energy services in some areas, while not excluding lower-tier improvements in others. Some replicable “bundling” (i.e., combining cooking and electrification, loans and grants) experience may be emerging regarding a Rwanda project co-financed by the Clean Cooking Fund at the World Bank’s Energy Sector Management Assistance Program.

Option 3: Modern Energy for All

- Goal: to bring access to modern energy cooking services (Tier 4 or 5) to everyone in the world

- Strategy: to empower countries to move toward only modern cooking fuels and technologies — including electric cooking, advanced biomass, liquid petroleum gas and ethanol

- Tactics: Establish international agreement on this overarching modern energy goal; conduct country-by-country assessments of the modern cooking industry’s capacity and needs; execute five-, 10- and 15-year plans to build out sub-sectors, including those focused on large-scale behavioral changes; provide well-targeted subsidies, incentives — and disincentives (for any cooking solutions under Tier 4 and 5); deploy specialized capital to assure the affordability of modern cooking solutions.

- Benefits and costs: This approach would eliminate indoor cooking-related pollution and its multi-trillion-dollar annual public health, environment and societal costs. It would reduce the drudgery and gender discrimination inherent to traditional cooking, providing major time savings (primarily) to women and girls. But it would require $1.5 trillion in investment and would lead to the loss of policy and resource support to the traditional (Tier 0) and improved (i.e., Tier 1-3) cookstove sector, implying a responsibility to retrain many thousands of workers.

- Comment: This option may not achieve the full expected public health benefit because it wouldn’t address non-cooking air pollution. It is as much as 15 times more expensive than moving people to Tier 3 cooking solutions. It would also invalidate the concepts of “technology neutrality” and country self-determination.

As these three options illustrate, there are multiple strategies that could move the world toward clean (or cleaner) cooking. But key stakeholders like the Clean Cooking Alliance and Dalberg need to recognize the ongoing and pressing need to establish a clearly articulated sector strategy, rather than simply issuing a set of ideas and oft-repeated talking points. For that to happen, not only CCA and Dalberg but all sector participants must take the opportunity to put aside their vested interests and pivot to an approach that can align country intentions, incentives, financing, behaviors and human capital.

The current situation is not irreparable, but time is of the essence. Without a clear path forward, the clean cooking sector will fail — it’s not a question of if, it’s a question of when. Influential stakeholders need to choose a realistic plan and implement it, before it’s too late.

Phil LaRocco is Adjunct Professor of International and Public Affairs at Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs.

Photo credit: Craig Taylor.

- Categories

- Energy, Environment