Bringing Cooking Poverty off the SDG Sidelines: A New Study Takes a Fresh Look at the Clean Cooking Challenge

Energy access professionals know a lot about dirty cooking and cooking poverty – i.e., the use of wood, charcoal, dung or other solid fuels to cook on three-stone or low-quality stoves in poorly ventilated conditions. They know the problem negatively affects almost four billion people and kills over 4 million each year – more people than tuberculosis, malaria and HIV-AIDS combined. They know that this damage primarily impacts women and girls, who are generally responsible for meal preparation in emerging countries. They know the root causes of cooking poverty: patriarchy and discrimination, overall poverty, dependency on available fuels, and lack of choice.

But though energy access professionals are well-aware of the impacts of cooking poverty, the problem and its solutions are pretty much invisible to the world at large – and even, to a lesser extent, to the broader development sector. Groundbreaking work published by the Energy Sector Management Assistance Program in 2020 showed that the cost of inaction ($2.4 trillion each year) is exponentially higher than the estimated one-time cost of eliminating dirty cooking – which ranges from $10 billion a year over the course of a decade (if the goal is to reach improved cooking for all) to as much as $156 billion a year (if the goal is to achieve modern cooking for all). Even $156 billion per year would be a fraction of the annual cost of fossil fuel subsidies, yet the international community invests only around $131 million per year – which amounts to 3.4 cents per capita.

This lack of attention, awareness and urgency around cooking poverty threatens to turn the entire Sustainable Development Goal edifice into an SDG artifice, making it impossible to achieve Goals 1 and 2 (Poverty and Hunger), Goal 5 (Gender Equality), and of course Goal 7 (Sustainable Energy). Failure to eradicate cooking poverty also greatly reduces our ability to accomplish five other SDGs.

It’s time for us to bring clean cooking off the sidelines of the development sector, which has long relegated it to a lower position than electrification, decarbonization and energy efficiency on the SDG agenda. Cooking poverty remains one of the largest unsolved public health and equality crises humanity has ever experienced. Below, I’ll explore why previous (and ongoing) efforts to address this crisis have failed and outline some potential solutions that could finally turn things around, based on a recent study out of Columbia University.

A Damning Diagnosis of Current Clean Cooking Strategies

Between January and June of this year, a team of seven graduate students at Columbia University’s Sustainable Management Program set out to analyze this issue from a more comprehensive perspective. They conducted this assessment while a major “ecosystem strategy” exploration was underway at the Clean Cooking Alliance (CCA), which was working with the consultancy Dalberg to determine how the sector could overcome a longstanding lack of progress toward ending cooking poverty. Based on the advice of the Clean Cooking Alliance, the team did this independently of the CCA/Dalberg work, so that their findings could be stacked up against each other. (For more on the CCA/Dalberg strategy, read my analysis in an article published on NextBillion shortly after its release.)

The result was a damning diagnosis of the clean cooking sector, consistent with the insights the CCA/Dalberg published as part of their ecosystem strategy – and a promising but challenging set of recommendations. The students titled their study “Killed by Breathing,” drawing upon a quote in a 2016 report from the World Health Organization, stating that “…women and children are killed by the everyday act of breathing, in what should be the ‘safety’ of their own homes.”

The study built upon a set of insights that the CCA and Dalberg compiled in the early stage of their ecosystem strategy work. These insights highlighted the following challenges:

- Ideas are not collectively shared across the sector, and knowledge loss is significant.

- Clean cooking lives in the shadow of national energy efforts, even though cooking is integral to the goal of achieving energy for all.

- The clean cooking sector’s inability to accelerate progress since its creation in 2010 has undermined its ability to attract investment and resources.

- There are institutional biases toward high-visibility initiatives rather than sector-changing strategies.

- Solutions are largely local and underfinanced. For instance, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are critical to the delivery of incremental cooking improvements to low-income segments. However, these SMEs tend to offer affordable but lower-tier solutions that employ biomass, rather than higher-tier solutions based on cleaner fuels and electricity. SME financing largely ignores cookstove and fuel SMEs which offer improved cooking, focusing instead on providers of higher-tier, more expensive modern cooking solutions. This funding approach excludes cookstove artisans with proven business models that may already serve over 10 million customers without subsidies.

- Biomass is the only uniform solution for many population segments that lack access to or cannot afford modern solutions such as electricity, liquefied petroleum gas and biofuels.

- Adjacent sectors such as public health, enterprise creation and gender empowerment represent potential strategic partners to attract capital and achieve SDG 7 – Sustainable and Modern Energy for All. But pragmatic “asks” of adjacent sectors are not sufficiently compelling, as shown by the failure of clean cooking advocates/organizations to attract cross-sector collaboration.

- End-users are often not involved in solutions, local markets or politics, which results in “top-down” solutions that can be at odds with the needs of the ultimate end-users.

These insights provided a foundation for the study’s own outreach to clean cooking participants, advancing the hard work of trying to conduct a sector-wide analysis of this diverse system.

A Generalized Model to Address Cooking Poverty

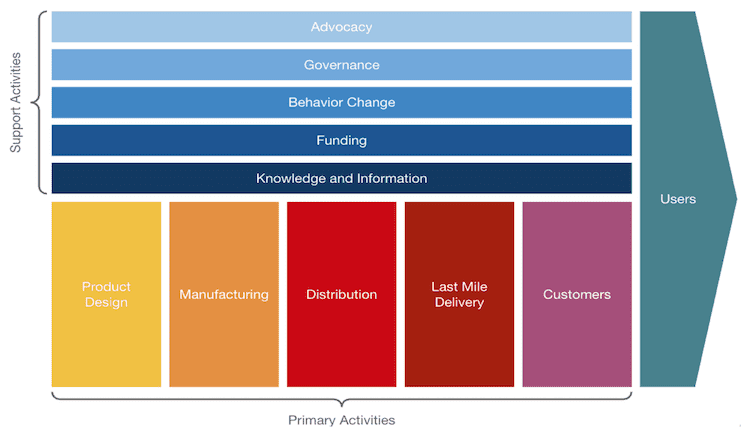

From these and other observations, the student-researchers created their own generalized model of the value chain or system that drives the clean cooking sector. And, more importantly, they identified significant gaps in this system.

Their generalized model sees the system as a set of primary and support activities, leading to the all-important goal of delivering improved or modern cooking to end-users, as illustrated in the graphic below.

The student-researchers then explored the gaps they’d identified in just the support activities (they very reasonably set aside the task of describing the entire universe of primary actors and activities). They summarized these observed gaps as follows:

- Advocacy Gaps include a lack of consistent messages, a failure to coalesce around a common approach to resource aggregation and deployment, and confusion between objectives for improved vs. modern cooking and stove/fuel standards.

- Governance Gaps include a lack of coherent sector strategy combined with too much ad-hoc work in implementing technical assistance, policy and regulation – along with inconsistent national frameworks to support in-country progress towards SDG 7.

- Behavior Change Gaps include the broad failure of sector actors to emphasize cooking poverty as a “people problem” as well as a fuel, appliance and finance one, and to incorporate end-user needs and behaviors early and deeply in the planning process.

- Funding Gaps include insufficient lending, poor disbursement with too few countries and solutions receiving the majority of funding, underutilization of carbon finance, and a lack of intermediation to align funders with solutions.

- Knowledge and Information Gaps include the overall siloed and ad-hoc nature of the sector, lack of an easy-to-access, easy-to-use platform for knowledge-sharing, and insufficient empowerment of entrepreneurs to encourage successful initiatives to scale up.

Finally, the student-researchers assembled and circulated a 50-page draft report to all of their advisors (full disclosure: I was one), and to a diverse set of industry colleagues. In their draft they included a roster of solution sets. These recommendations included:

- Advocacy: Rebrand the issue to term it “cooking poverty” rather than “clean cooking.” Frame the issue as a problem on the scale of HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis. Apply consistent rather than ad-hoc messaging. Use “success stories” – but only in conjunction with messages about what is still needed to achieve scale.

- Governance: Negotiate a donor-lender-investor “compact,” spearheaded by influential sector stakeholders and funders, to establish a complete and balanced approach to fundraising, technical assistance and policy creation. Codify standards for in-country consistency and empower clearly responsible country agencies and action plans for progress at the local, national and (where appropriate) regional levels.

- Behavior: Build a final strategy around a country and enterprise focus, featuring collaboration with local community organizations committed to incorporating behavior change and end-user engagement into every step of implementation, as this is essential to project success.

- Funding: Focus on balanced investment across the entire value chain, utilizing mechanisms such as results-based financing, carbon finance, microcredit and intermediaries. The above-mentioned donor-lender-investor compact could help guide this approach.

- Knowledge and Information: Centralize sector knowledge and experience in a collaborative, timely, experienced-based repository – i.e., a “playbook.” The playbook should ensure that all actors and new participants have access to easy-to-use solutions of all types and tiers, and should identify experts across the value chain to ensure synergy rather than competition.

The study team then translated this work into a series of five action items published by Sustainable Energy For All. The hope is that the team’s thinking will be integrated into the ongoing ecosystem strategy work of the Clean Cooking Alliance, Dalberg and others. Many of the team’s observations and recommendations line up well with that body of work, but some of its points and implications require more back-and-forth.

The end result remains to be seen, but this study already illustrates two promising things: First, it shows that the learning curve in clean cooking can be overcome with moderate effort in a reasonable period of time, as evidenced by the student-researchers’ success in adding their voices to the cooking poverty conversation. And it demonstrates that the debate about the scale of strategy, tactics and solutions remains an important and ongoing one in the sector.

Phil LaRocco is Adjunct Professor of International and Public Affairs at Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs.

Photo courtesy of sandeepachetan.com travel photography.

- Categories

- Energy, Environment, Impact Assessment