How Should We Measure Impact? We Asked Our Investees.

“If you want to want to watch a panel of impact investors engage in circular, evasive and tongue-tied banter, all you need to do is ask ‘How do you actually measure impact?’”

– Greg Neichin, Co-Director, Ceniarth

It might go without saying that as an impact-first investor, we at Ceniarth must understand the impact of our investments. On the surface, this statement sounds obvious, but we are fully aware that impact measurement is not straightforward. We steward an impact-first portfolio of over 75 fund and enterprise investments in five sectors, with a total of around $150 million in commitments that grows every year by $30-$50 million. Understanding the social impact of those investments is a complex endeavor.

This complexity is why Ceniarth brought me on as an experienced professional devoted exclusively to impact. It is why we begin our origination process with questions about impact, not financials. And it is why we have made investments in industry tools that help us evaluate the effectiveness of our interventions, such as 60 Decibels’ Lean Data. But even with our commitment and resources, we have found that there is no simple solution to measuring impact well.

We initially considered doing what many others do, developing our own impact framework that keeps things manageable by finding a small set of common indicators and requesting standardized data from our investees. While this approach would have simplified the exercise, we knew that it would only tell a fraction of the story – and that it would overlook multiple factors, beyond just our investment, that were responsible for impacts in communities. In grappling with the complexity of assessing impact across our portfolio, we decided recently to start from the source of our data: our investees. We decided to ask all our investees some very basic questions: How do they measure impact? Which metrics do they track? And which barriers do they face?

This article describes what we did to understand our investees’ impact monitoring, what we learned, and what we can do with these insights. As expected, we found no silver bullet – but we did develop a much better mapping of our impact landscape. Impact data will always be messy, and impact management is both complicated and resource intensive. But we feel that engaged investors can work in both a “bottom-up,” deal-by-deal way, as well as a “top-down,” portfolio-wide manner, to guide investees toward deeper impact.

What did we do to understand our investees’ impact monitoring?

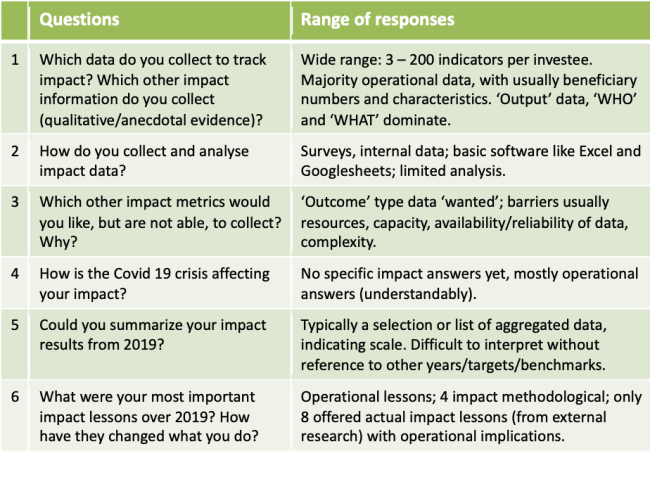

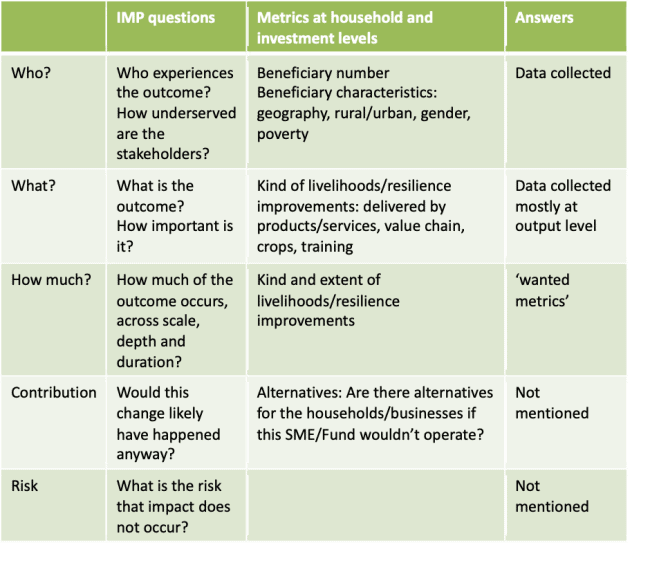

As part of our regular quarterly monitoring cycle in April 2020, we asked all of our investees the six questions in the table below. With many of them continuing to be stretched thin by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, we wanted to ensure that the questions were easy to answer, yet sufficiently informative to produce insights. We allowed our investees, a sample size of around 50 for this cycle, to respond via email or during a call. The response rate was 86%. We then analyzed the answers according to two frameworks: the Impact Management Project (IMP) framework and the commonly-used theory of change framework, which describes social change in causal links – connecting investment dollars to inputs, which then lead to outputs, outcomes and impact.

What did we learn about the impact monitoring of our investments?

In short, we found a huge range of responses.

The metrics our investees collect ranged from three to over 200 indicators per investee. Given the breadth of our portfolio, this might not be surprising. Our portfolio focuses on improving rural livelihoods, and spans both fund and direct investments. It includes a variety of debt instruments, and covers five main sectors: agriculture, financial inclusion, community development, energy access and SME finance. All of these have varying business and operational models, so obviously the metrics used by each investee were different. Moreover, even with similar metrics, investees’ methodologies differed, which further inhibited straightforward comparison or aggregation.

While we found variance in the types of metrics and methodologies used by our investees, mapping these questions against IMP’s impact model – as shown in the table above – did serve to highlight some consistencies, as well as gaps in their impact measurement efforts. For example, most metrics were aimed at assessing “Who experiences an outcome?” and “What is that outcome?” – and investees were most likely to have data about these metrics. “How much of the outcome occurs?” wasn’t as commonly measured – most investees responded that they wanted data but were not able to collect this kind of data. Meanwhile, “contribution” and “risk” were not mentioned as part of impact monitoring by any investees at all.

Even the “Who?” is tricky

Beneficiary data should offer a sense of the scale and reach – if not the depth – of impact. The most common data we were given pertained to numbers of beneficiaries and jobs supported, which would seem the most straightforward to collect.

But that was not so. We found that even these basic counting metrics can be complicated to interpret – let alone to compare and aggregate. Some of our investees only counted individual direct beneficiaries, while others included indirect beneficiaries too. For example, some investees would multiply their beneficiary numbers by four or five, aiming to represent the full number of dependents in an impacted household.

Given the breadth and overlap of our portfolio funds and enterprises, “double counting” can also be tricky to correct. It happens when the same beneficiary is counted multiple times. This could occur when a client takes a repeat loan, benefits from multiple products or services (such as a loan and a training course), or benefits over multiple years. The same beneficiary can also be counted multiple times if an investor is committed to multiple funds that invest in the same business. Over-claiming impact is difficult to avoid too. Funds and businesses generally receive capital from various investors, and because it is impossible to attribute their specific impacts to an individual investment, typically all investors claim all impact.

Similarly, employment data (in terms of numbers of jobs) can be confusing to interpret. Is an investee including jobs created, sustained or supported? Are they including part-time, seasonal, temporary, contracted and non-contracted employment? Is the data gathered up to the current date, or at year-end?

Moving beyond numbers, the characteristics of the beneficiaries matter – for example, whether they’re poor, rural, female, etc. This data requires further measurement. For instance, how does the investee know whether their beneficiaries are poor? Do they have direct interaction and can they actually ask for personal income data? If not, which proxies or estimates do they use? Do they assess individual poverty compared to a local or international poverty line? If so, at what point in the year do they make that assessment? Fund investors generally rely on their underlying investees to access, collect and supply this sort of data. Unfortunately, this more detailed data collection process requires resources and expertise that is typically lacking in the field.

Outputs, Outcomes – and how it all adds up to Impact

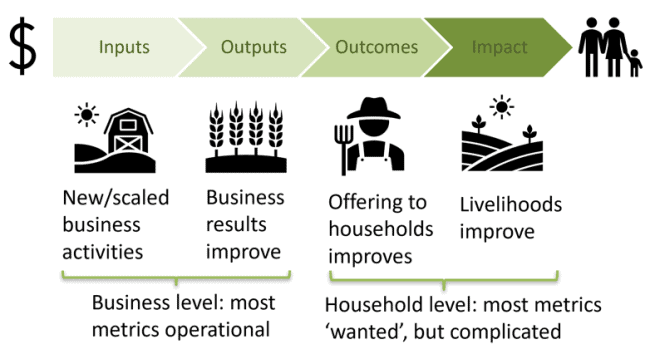

Looking beyond the “Who?” to the “What?” and “How Much?,” we found that most data collected by our investees was limited to outputs, as opposed to outcomes or impact. The distinction between these terms is based on traditional theory of change categories. The chart below (showing agriculture investments) illustrates that investment dollars, either provided directly from us or via a fund, are inputs facilitating new or scaled business activities. Ideally, they help businesses to grow and results to improve, generating output data. Metrics on these inputs and outputs are operational data at a business level. As we move towards outcomes, the focus shifts to how business offerings are improving the lives of households. The impact, ultimately, is whether these beneficiaries actually experience livelihood improvements as a result of our investments.

Investee businesses should have full visibility into how our investment has supported new or scaled activity, which can include anything from new warehouses built to new technologies adopted. Both direct and fund investees typically share this input data as Key Performance Indicators or financial and operational updates during quarterly monitoring cycles.

In terms of the results of these activities, most of the data our investees collect are operational outputs, such as the number of clients or products sold. Most of our investees stop here, and use these outputs data as indicators for impact. This can be okay when the product or service is closely related to providing or offering social impact. However, as we have seen in sectors such as financial inclusion and energy access, the mere availability of a product or service does not always directly translate into household benefit, nor does it tell us anything about the magnitude of that impact.

As much as we would like to see our investees and the sector at large move beyond the simple tabulation of outputs, metrics on outcome and impact are notoriously difficult and costly to obtain as they move towards the household level. Even when collected, they tend to be easy to dismiss as imperfect. When we asked our investees about the metrics they wanted to track but could not, most cited these outcome and impact metrics.

What gets in the way of greater impact clarity?

Most investees cited the lack of dedicated resources, lack of technical capacity, general complexity, and lack of reliable data as key barriers. Data collection is resource hungry, and most investees are still using basic software such as Excel or Google Sheets to collect and aggregate data. Those who make use of surveys and call centers as part of their core operations leverage these capabilities when they can to enhance impact data, but this is the exception.

The number of professionals at our investee businesses who are focused on impact measurement varied widely. Most smaller, early-stage enterprises lack any dedicated staff for these tasks, while larger, more established fund managers have up to five full-time professionals on their impact teams. Clearly, these resourcing disparities directly affect investees’ bandwidth to collect and analyze data.

An interesting finding is that impact data is collected not only to improve impact. Fund managers indicate that it is required for investor diligence, enterprises collect it as a way to improve operational management, and both types of investees point out that it is necessary for investor and other stakeholder reporting. Most of our investees track data as part of their operations, and use it as proxies for impact (e.g. products sold). Around a third of investees produced some form of impact material, ranging from a fact sheet or dashboard to impact reports.

Another non-intuitive finding is that direct impact monitoring does not automatically generate actionable impact insights. Impact data requires further analysis and action to actually improve impact. Only a few investees said that they made operational changes based on impact learnings, and these were typically from external research and case studies rather than from their own impact monitoring only. Again, lack of resources and capacity gets in the way.

Key Take-Aways for Investors

Surveying our investees yielded a wide range of responses and gave us greater insight into the variability of their impact measurement approaches. Of course, the exercise offered no neatly wrapped answer as to how we, an impact-first investor across a variety of interventions, should be approaching monitoring.

However, we will implement a number of key learnings, which may be useful for other investors looking to deepen their impact measurement practices. We suggest combining a top-down with a bottom-up approach: providing investees with guidance to help them generate focused thematic insights, while accounting for their diversity and meeting them where they are in terms of impact monitoring. There are two reasons for this approach:

- Impact data will always be messy, and aggregating and comparing data from funds and direct investments across sectors is not particularly meaningful. This implies that when a portfolio, like ours, is diverse, identifying common metrics to collect and aggregate across all investees may not be the best approach. Instead, a top-down approach that focuses on insight creation and uses a consistent objective to generate actionable insights, rather than consistent metrics, can help strengthen our understanding and produce relevant segmented learnings. This typically requires external research and a dedicated budget.

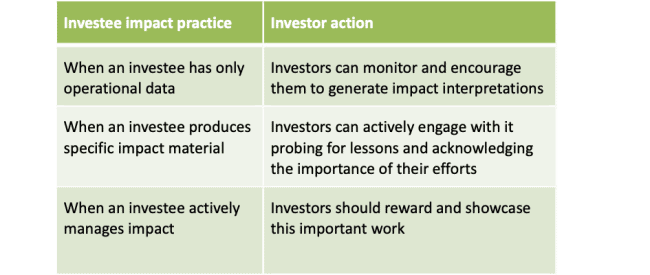

- Monitoring and managing impact is complicated. It requires effort, resources and encouragement to generate lessons and actionable insights. Active impact management goes beyond monitoring. It must build on investment due diligence, utilize findings from monitoring and both internal and external research, push towards lessons and actionable insights, and ensure that actual changes are executed in operations that maximize impact. As an investor, we can use a bottom-up approach for deal-by-deal monitoring, tailored to the level of impact practice of our investees, as in the table below.

At each of these levels we can, when appropriate, consider funding projects that support investees’ desire to deepen their impact learnings. For example, we have provided grant funding for a cohort of our agricultural enterprise borrowers to engage with 60 Decibels’ Lean Data methodology to assess customer impact. And we have recently committed to a similar 60 Decibels project for organizations in our Community Development Finance Institution portfolio.

To build our impact understanding, we will devote meaningful internal resources – such as time from our impact and investment managers. While this comes at a cost, it would be hypocritical for us to be a prominent industry champion for impact-first investing without devoting appropriate attention to ensuring that we are having the intended impacts. As we move forward with these efforts, we will continue to share our insights transparently, in an effort to help other investors and investees make the most out of impact monitoring and work towards impact management. Ultimately, the more we engage with the messy, complex world of impact, the more efficiently we will deploy capital to benefit underserved communities.

Julia Mensink is the senior impact manager at Ceniarth.

Photo courtesy of Ricardo Arce.

- Categories

- Impact Assessment, Investing, Social Enterprise, Technology