India’s Business Correspondent Model is Revolutionary – and It’s Failing: Here’s How to Turn Things Around

India has traditionally been an under-banked country, with a banking system that doesn’t work for poor and hard-to-serve populations. One key reason for this is the fact that most transactions are conducted in cash, and “brick and mortar” outlets make cash-based services expensive. Moreover, low-income households don’t see much value in opening a bank account only to store a small amount of money. Given their limited literacy levels, they struggle with the inflexibility of branch banking, which involves various forms of documentation and other formalities. Since banks pass the costs of handling cash transactions – and of storing, transporting and processing cash – along to their customers via fees, it becomes hard for low-income customers to absorb these costs. And besides being intimidating and costly, traditional banking requires a trek to a local branch, which can mean the loss of a day’s wages.

But the global revolution in technology, along with rapid advances in digital payment systems, is creating opportunities to connect poor households with affordable and reliable financial tools.

The most revolutionary approach for efficient last-mile delivery of financial services in India is the business correspondent (BC) model — an equivalent to the agent network that enables mobile money services in Kenya. Remote Indian villages lack bank branches, but they do have other retail outlets, such as convenience and grocery stores, pharmacies, kiosks and post offices. These outlets provide locations for a network of agents that can be used as low-cost delivery channels for providing financial services to people visiting them – particularly in rural areas that are financially excluded from mainstream banking. The BC model is aided by technology-oriented tools, such as point of service handheld devices, mobile phones, biometric scanners and even micro ATMs.

Taking Banking to the People

The business correspondent model typically involves an agent as an extended arm of the bank — an important piece in the financial ecosystem and a key touchpoint that enables banks to expand their outreach dramatically at substantially lower cost. The model was introduced in 2006 by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to allow banks to have third-party, non-bank agents that extend their services right to customers’ local communities. The BC model proposes that in areas inaccessible to banks, entities such as grocery stores, petrol stations, telcos and other companies with a retail network can be authorized to perform financial operations on behalf of the bank. These operations can include opening and maintaining accounts, handling small value loan proposals, and providing other basic services. Every BC is required to be attached to and overseen by a designated bank operating in its general vicinity.

Business correspondents are typically grassroots entrepreneurs who serve as contractual representatives of the sponsor bank and are authorised to conduct specified business on its behalf. They are compensated through fees and commission paid by the sponsor, which also takes care of their training needs. Since they belong to the same community, they have local knowledge, and greater understanding of the issues specific to the rural poor, and they enjoy greater acceptance amongst them. They also have flexibility in operations, such as being available round-the-clock, which provides a level of comfort to their clientele that lets them better serve the population.

For banks, some of the advantages of using business correspondents are:

- Greater reach: By using BCs, banks can reach out to areas that lack formal financial services at a much faster rate and lower cost than they can by building brick-and-mortar branches.

- Doorstep banking: The use of BCs enables banks to provide banking services, including loan disbursement and recovery, at convenient locations or even door-to-door.

- Better loan performance: Since local stakeholders are involved in the process, they know the customers at a personal level. This strengthens borrowers’ accountability to the BC, which in turn improves loan performance and repayment rates.

Challenges of the Business Correspondent Model

Though India’s progress on financial inclusion is considerable, it is far below expectations – and the business correspondent model hasn’t been able to change this outlook. According to the 2017 Findex report, 80 percent of Indian adults now have a bank account—27 points higher than in 2014. And 77 percent of Indian women now own a bank account – compared to 43 percent and 26 percent in 2014 and 2011, respectively. Yet this progress is tempered by the fact that around 48 percent of these bank accounts have seen no transactions in the last year, and that India has the world’s highest share of inactive accounts – about twice the average of 25 percent for developing economies.

The BC approach has been hampered by:

- Operational hurdles: BCs have struggled particularly with problems involving cash handling, like transporting and safeguarding cash, and avoiding fraud and misappropriations. BCs also have limited overdraft facilities and transaction limits that may not be adequate for the daily requirements of their account holders.

- Viability issues: Despite an increasing level of awareness about the value of banking services, the majority of accounts opened by BCs are inactive. As a result, there is a shortage of funding for building BCs’ capacity and expanding into unbanked areas. In some cases, BCs have lost money, leading to significant attrition And expanding into unbanked areas involves costs that banks find difficult to cover.

- Regulatory concerns: Current regulations require BCs to complete accounting and settle withdrawals with bank branches within 24 hours of a transaction. But this may not be possible due to the distances involved, and the fact that absence from their centers can affect BCs’ business.

In light of these challenges, it is now becoming clear that business correspondents may not be able to handle the entire range of banking services, particularly more advanced credit functions. It is only larger entities, with competent manpower and proper logistical support, which can handle the credit functions required of modern banks– at least until BCs acquire the necessary expertise and support.

Helping Business Correspondents Succeed

Nevertheless, BCs can remain an important part of overall financial inclusion efforts. To maximize their effectiveness, efforts must be made to train them and enlarge their responsibilities in a graduated manner. For instance, when business correspondents reach a higher level of business volumes, they can be endowed with greater responsibilities that may include more comprehensive credit services. India also needs a graded system of certification for business correspondents, from basic to advanced training, to arm them to perform different levels of financial tasks.

Some other urgent reforms that could improve the efficacy of the business correspondent model include:

- Establish a Self-Regulatory Organisation for business correspondents. The initiative for this organization would obviously have to come from the BC community and may be monitored by the Indian Banks Association (a pan-India federation of banks) or the RBI. The organization would help set standard rules and formulate a code of conduct for effective monitoring and supervision. It would also act as the legitimately recognised interface between BCs, banks, the RBI and the government.

- Set up an independent agency for undertaking geo-tagging and GPS mapping of agent locations to enable better monitoring and supervision of agent points.

- Undertake the planned growth of BC networks by expanding both the customer base and the network in tandem. To achieve this, banks must enrol agents who have the right skills, mindset and commitment, and introduce a proper system for training and retraining them. Banks should also consider providing manned mobile offices that visit BCs at their locations to settle daily transactions, addressing the challenges of the transport of cash.

- Reduce the time required for transactions to bring down incremental costs for agents, thereby enhancing the viability of their operations. This could be facilitated by riding on the national digital infrastructure, and by having unified know-your-customer guidelines, simplified processes and workflow-based solutions.

- Enable agents to source credit with innovative risk-sharing mechanisms, and facilitate data analytics-based digital credit models. This can boost revenue, make investments available for upgrading technology, and make credit more inclusive.

- Improve BC compensation structures to enhance agent viability. This will require a nuanced understanding of the agent economics and risk — and the business case for agents is not that simple. BCs’ activities are typically limited to opening new deposit accounts for a commission. But with villages becoming oversaturated, the opportunity to open new deposit accounts – particularly after the success of the Jan Dhan Yojana financial inclusion scheme – has been exhausted. This will need to change – and since banks’ lending activities through BCs are very limited, agents will need to be supported to build adjacent revenue streams.

- Develop new technology to allow a BC to act on behalf of multiple banks—something that might only be possible if all the banks use a single data-sharing platform.

- Route all government payments, including pension and social security payments, through banks. This would boost the volume of transactions that take place through BCs and, consequently, make the BC model more viable.

India has an expansive network of BCs – around 500,000 in rural areas and 150,000 in urban areas, almost six times the number of bank branches. The learning curve for them is steep, and so is their costs curve if they have to sustain their operations while at the same time ensuring that their services are affordable to users. They require fixed investment and support with substantial upfront costs, so scale is necessary to recoup this investment. Unit costs decrease as more value flows through the system, but fixed costs are hard for small providers to shoulder.

The country needs a larger force of agents – educated, motivated and savvy enough to effectively reach remote and challenging communities. But considering the work required for on-boarding these customers and orienting them to actively use digital services, BCs’ compensation appears to be hardly worth the effort. On account of this, business correspondents tend to favour densely populated, well-monetised and oversaturated markets. The original business correspondent model of doorstep banking has already given way to kiosk-based banking due to the increased workload required of BCs.

Steps in the Right Direction

Fortunately, the government clearly recognizes this reality, and one transformative development in the BC space has been the RBI’s decision in 2014 to allow microfinance institutions to act as business correspondents. This has led to the diversification of products and services and the improved availability of credit. Further, the government is transferring large amounts of government benefits through BCs via direct benefit transfers, so the viability of the model should improve. However, bank branches still need to evolve proper mechanisms for handling large cash payments at BC points, as the cash retention limits of BCs are not commensurate with the large amounts often involved in these transfers.

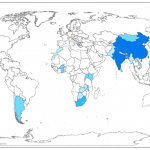

Yet it is far from clear that banks have cracked the dynamics underlying the BC model. To achieve scale and keep costs manageable, they must adopt varied agent models—ranging from full-time “wealth advisors” to part-time “lite” agents who just focus on a few simple transactions, and who are not solely dependent on the BC business for their income. (Currently, almost two-thirds of BCs in India are dedicated, full-time agents, far higher than in other countries such as Kenya, Pakistan or Bangladesh.) And to make the agent model more sustainable, banks must diversify and expand the portfolio of products sold by agents to include higher margin products such as loans or investment products.

Meaningful financial inclusion will be possible in India only if BCs provide quality services with transparency and dignity to the country’s underserved populations. But BCs need financial stability for themselves before they can be expected to extend financial inclusion to the unbanked and serve a new generation of account holders.

Moin Qazi is an author, researcher and development professional.

Image courtesy of ILO in Asia and the Pacific.

Homepage photo: Asian Development Bank, via Flickr.

- Categories

- Finance