Business Solutions to a Humanitarian Crisis: Nine Things Companies Must Understand to Support Refugees from Ukraine – And Around the World

As the world watches the war in Ukraine with increasing alarm, much of the attention is understandably focused on the human casualties and physical devastation. But there is another concern that is both grave and growing: the millions of people who have been forced to flee their homes. In addition to the 7.7 million people who have been internally displaced within Ukraine (as of May 5), more than 6.6 million refugees have sought safety abroad (as of May 25). To help these refugees, governments, NGOs, multilateral agencies and individuals around the world have organized or supported humanitarian relief efforts. Yet these efforts are struggling to keep up with the needs of the growing number of Ukrainians who continue to seek refuge from the conflict.

Meanwhile, many people in North America, Europe and around the world have also been supporting the tens of thousands of Afghan refugees who have been resettling into their host communities. But despite their efforts, the needs of these refugees greatly outweigh the available support. Enlisting the private sector could help fill some of these gaps—whether the refugees involved are from Ukraine or other nations facing war or natural disaster. But how can enterprises best contribute to something that has traditionally been considered an exclusively humanitarian affair?

To answer this question, we can look at the recent past – starting around 2015, when global attention to the Syrian refugee crisis drove a significant increase in private sector involvement. No two refugee situations are identical, but a review of these recent activities can help inform efforts to support Ukrainian refugees in the present scenario. To begin with, these experiences help illustrate how different aspects of a crisis can give rise to various business models and strategies for leveraging private sector support. Below, I’ll share nine learnings from the refugee crises of recent years, which show how for-profit enterprises and their employees can serve and empower refugees while also benefiting host communities – and their own businesses.

1. Donating funds is the best approach in the earliest phase of a humanitarian crisis

In the earliest phase of a humanitarian crisis—when uncertainty and acute needs prevail—donating funds represents the most practical option for businesses that want to support refugees. The instability and unpredictability of these situations offer little latitude for enterprises to engage in typical revenue-generating activities—and meanwhile, on-the-ground aid organizations have an urgent need to ramp up operations.

Rather than stand on the sidelines when the Syrian refugee crisis intensified around 2015, enterprises responded by contributing funds to relief efforts. These donated funds came from a variety of sources, such as:

- The company’s overall earnings

- Grants from affiliated foundations

- Proceeds from the sales of designated products

- Employee contributions (sometimes encouraged and enhanced by company matching)

- Customer point-of-sale donations

This enterprise-led philanthropy has provided a critical lifeline to donor-dependent aid agencies, and has translated into assistance for millions of refugees in the most vulnerable situations. And at the same time, these efforts have produced benefits for the businesses themselves, such as improved brand equity: For instance, customers are more likely to purchase from companies that have made a sizable donation to support refugees. Similarly, companies can increase revenues when engaging customers directly on refugee support: For example, when Unilever earmarked the proceeds of some of its products in Lebanon to the UN Refugee Agency’s programs as part of an awareness-raising campaign, it increased sales of these products by 30% and raised $50,000 for Syrian refugee programs at the same time.

2. Different business models, products and services can be used to meet refugees’ diverse needs

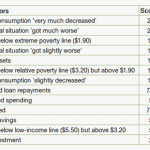

Enterprises can meet various refugee needs by providing their products, services and expertise directly to refugee communities, but the financial sustainability of these initiatives—and consequently the duration of their involvement—has varied. The Syrian refugee crisis and other recent refugee contexts have produced business models that have ranged from fully charitable (i.e., in-kind donations) to profit-making, with a range of “hybrids” (commercial efforts subsidized by donor funds) in between.

Fully charitable models—e.g., donations of shoes, bedding, educational content and other products—reflect businesses’ recognition that refugees’ needs often outweigh their means. While these initiatives are loss-making on the surface, they indirectly benefit the business by improving brand perception—just as much as financial donations do.

At the other end of the spectrum, refugees in more stable settings are able and willing to pay for goods and services that meet specific needs. Mobile connectivity is a prime example: Mobile operators in Turkey found that Syrian refugees spent more on prepaid mobile services – including approximately twice as much on international calls – as Turkish host-community users. So, to compete for these customers, companies have adapted their practices to respond to refugee needs—e.g., by increasing network coverage in refugee-hosting areas and creating tailored packages for refugees, or even by developing free mobile apps with refugee-focused content. Beyond telecoms, refugee camps and settlements have also been shown to offer a sizable market for a variety of goods and services, including financial products.

While financially sustainable models represent the “holy grail” of the private sector’s potential to meet refugee needs in a more lasting manner, in reality, refugee-focused businesses have typically involved a financial subsidy. Donors, eager to engage the private sector, have often provided some sort of concessional financing to lower the costs of serving refugees. This has been the case for Equity Bank, whose branches in Kenya’s Kakuma refugee camp profitably serve over 30,000 refugees and 60,000 host community members; its loans usually include some funding from development finance institutions. Similarly, in eastern Congo, the social enterprise Asili provides water, healthcare and agricultural inputs on a financially sustainable basis, although its setup costs were covered by donor funding.

In a “wholesale” version of the above models, enterprises have provided services, equipment and/or technical capabilities—e.g., cash transfer technologies and wireless infrastructure—to refugee assistance organizations. This highlights these organizations’ roles as important intermediaries and business clients—they possess the financial backing to afford such services, and/or the stature to attract pro-bono support. It’s unclear how many of these services were provided on a fully charitable basis versus a purely commercial one, or how many fell somewhere in the middle. But enterprises adopting this model have typically shared their technical capabilities on a pro-bono basis, while other projects have involved international donor agencies (suggesting that they were not otherwise commercially viable).

3. Making customers part of the business by employing refugees can increase impact

To help refugees achieve their aspirations of economic self-sufficiency—especially since they typically experience many years of displacement—many businesses, both large and small, were motivated by the Syrian crisis to hire refugees. There is significant scope to expand these practices going forward (in countries with amenable labor laws)—for instance, a consortium of over 45 British businesses has announced plans to hire Ukrainian refugees, using the tools and guidance created by organizations that advocate for refugee employment. The Tent Foundation, for example, has produced tailored guides on refugee hiring for enterprises in the Netherlands, Italy, Australia, Spain, France, the U.S., the U.K. and other countries. Meanwhile, the nonprofit Talent Beyond Boundaries has built the networks and expertise to help companies in the U.K., U.S., Australia and Canada source refugee talent globally. Multilateral organizations also continue their efforts to address the legal barriers that have constrained refugee employment in some countries.

4. Supporting refugees’ businesses is key to boosting their livelihoods

Businesses started by refugees themselves are an important—but often overlooked—component of the role of private enterprise in alleviating refugee crises. Refugee business owners not only create livelihood opportunities for themselves, they also provide jobs and services to other refugees in their communities. Yet entrepreneurial refugees still face significantly greater hurdles than the average entrepreneur, and established companies have a role to play in unlocking their potential. In recent years, some companies have begun to contribute funding, employee volunteers and/or other support to organizations—e.g., accelerator programs and community-focused financial institutions—that promote refugee entrepreneurship, although more is still needed. Other companies, like Ikea, have sought to source from refugee-owned businesses, though not all of these businesses are candidates for inclusion in supply chains.

5. It’s important to commit to the long haul, even after headlines fade

The average refugee experience lasts 10 – 15 years, but the burst of initial support from private sector actors—as well as the general public—has typically not translated into longer-term involvement. Since most initiatives have limited financial sustainability, enterprises have little incentive to continue them after public interest wanes and customer and employee focus shifts elsewhere. Indeed, after enterprises’ support for refugee initiatives ramped up in 2015 and 2016, it started to trend downward in the following years. In addition, based on my analysis of the status of pledges made at the 2019 Global Refugee Forum, only a fraction of businesses (12%) have fulfilled the pledges they committed to (amidst great fanfare) as part of the Global Compact on Refugees. Given this past trend, companies aiming to support refugees should commit in advance to multi-year efforts.

6. Not all innovations deliver their intended impacts

Based on the pattern of activity that followed the Syrian refugee crisis, we can expect to see a proliferation of inventive, entrepreneurial responses to help Ukrainian refugees. But while the potential for innovations (especially tech-led) can be an exciting prospect, these “refugee-impact” ventures or initiatives often fall short of their aspirations. As founders of two tech-based refugee-focused ventures—NeedsList and Tykn Tech—have cautioned their peers, innovations developed far from refugee communities risk failure by missing the mark on refugees’ needs or adoption patterns, or by underestimating the challenges of rolling out in distant, complex settings.

Additionally, since ambitious solutions have often arisen from within the venture capital ecosystem—rather than the development impact space—their teams have rarely adopted the established practices of impact measurement. This matters because a highly-scalable concept is of questionable value if there is no evidence to show how many refugees it has actually reached—let alone to what degree it has benefitted them. The resulting outcome is a landscape littered with many failed startups, which captured the attention (and resources) of the social impact ecosystem—but in reality lacked the viability to get off the ground. The business world encourages self-reliance, but we should avoid the assumption that experience in one sector translates into expertise in refugee-related contexts.

7. Flying solo doesn’t work—partnerships are essential for effective impact

Enterprise leaders and entrepreneurs who are newly motivated to assist refugees may have a blind spot when it comes to the existence of other organizations that are already active in this field. They should enter into this work with the assumption that regardless of the nature of their initiatives, there is a partner already well-positioned to provide guidance, cooperation and/or potential access to helpful resources. (Some recommendations for successful partnerships are found in this IFC study.)

8. The host community also needs support

An influx of refugees can strain the infrastructure and resources of host communities—many of which have their own economic challenges. For this reason, enterprises should plan their programs and partnerships in ways that also support host community needs, and that enhance social integration between refugees and their surrounding communities. This approach could include working with accelerator programs that train both host community and refugee entrepreneurs, among other options.

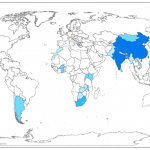

9. The current refugee crisis is only part of the challenge – and opportunity

As of mid-2021, i.e., well before the invasion of Ukraine, over 30 million people in the world had refugee or refugee-like status—including 2.6 million from Afghanistan, 6.8 million from Syria, 4.1 million from Venezuela, and millions more from other countries. No matter where a particular business operates, chances are that there are refugees in its midst—in fact, 14% of refugees reside in developed countries. Even refugees in other geographies can offer value directly related to an enterprise’s core business, in the form of professional skills/human talent, supply chains or potential technology partnerships. Supporting already-resettled refugees—such as via hiring or entrepreneurship support—supplements the capacity of refugee assistance organizations, and thus indirectly helps benefit people with more acute needs, such as those in the process of fleeing Ukraine. Moreover, it creates the same types of positive outcomes that motivate enterprises to help those whose lives have been upended by the war in Ukraine: alleviating human suffering and unlocking refugees’ potential to contribute their talents and capabilities to the global community.

The varied initiatives discussed above provide both excellent examples of how enterprises have worked to support refugees displaced in previous crises, as well as warnings about the pitfalls they’ve encountered when good intentions didn’t equate to good outcomes. On the positive side, companies’ collective efforts provided a great deal of support of various kinds in recent years, and many companies have subsequently supported refugees in other emergencies. And cross-sectoral collaboration among the many businesses that are engaged in this work has resulted in knowledge-sharing and recommended good practices. But on the other hand, these initiatives did not truly live up to their potential to support refugees beyond the short term. Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, evidence suggests that overall, these initial activities failed to solidify into a consistent, effective effort to reduce refugees’ challenges.

Nevertheless, it is promising to now see a number of companies launching initiatives to help Ukrainian refugees. But if they hope to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past, and to make a genuine impact on refugees from Ukraine, Afghanistan and other countries, enterprises and other organizations should be aware of the challenges and failures of past efforts to leverage business tools for the benefit of refugee populations. The insights discussed in this article can provide them with guidance to draw from, as they consider how to support refugees in 2022 and beyond.

Betsy Alley is an independent researcher and analyst focusing on issues related to impact investment and development finance.

Photo courtesy of manhhai.

- Categories

- Investing