India’s Unconventional COVID-19 Recovery: How Platformization and Digitalisation Can Build an Inclusive Post-Pandemic Economy

As the COVID-19 crisis continues, pandemic-induced restrictions and lockdowns continue to present challenges to the way we work. In India, where close to 92% of the labour force is employed in the informal sector, the repercussions of these challenges are being felt throughout the economic landscape. In May 2020, ActionAid’s National Study on Informal Workers revealed that over 78% of the country’s informal workforce had lost their livelihoods due to the lockdown. The same workers, when revisited in Round II of the study (published in February 2021), showed slow recovery post-lockdown. Around 52% were now employed part-time, either working occasionally or putting in fewer hours than their pre-lockdown level, while close to 40% remained unemployed. However, there has also been a silver lining behind these dark clouds – accelerated digitalisation and platformization.

Physical distancing mandates and restrictions on free movement have been progressively pushing India’s people towards digital modes for day-to-day activities since the pandemic began. In areas ranging from healthcare and grocery delivery, to personal care services and even financial transactions, 2020 represented a leap towards a more digital economy. The 2020-21 Annual Report from the Reserve Bank of India, the country’s central bank and regulatory body, noted that India’s total number of digital transactions had increased to 43.71 billion from 34.12 billion in 2019-20. Meanwhile, the value of digital transactions made through the Unified Payment Interface system alone doubled from Rs 21.3 trillion ($284.2 billion) in 2019-2020 to Rs 41.04 trillion ($547.09 billion) in 2020-2021.

The year also saw gig/platform workers emerge as the common thread bridging the demand and supply of essential goods and services, making them a key part of keeping the economy running. A gig worker is a person who engages in income-earning activities outside of a traditional employer-employee relationship, as well as in the informal sector. When gig workers use platforms – i.e., websites or apps like Ola, Uber, Dunzo, Zomato or Urban Company – to connect with customers, they are called platform workers. From enabling the movement of frontline workers during the lockdown, to delivering essentials like food, groceries and medicines, a plethora of platforms stepped up to the challenge of providing uninterrupted services in spite of the crisis.

As most platform businesses rely on mobile-based apps accessed on affordable mobile devices and cheap data plans, their potential is only likely to grow. According to the IAMAI-Kantar ICUBE 2020 report, the number of active internet users in India is expected to increase by 45% between 2020 and 2025, growing from 622 million to 900 million. This burgeoning access will enable existing platforms to scale, and new ones to emerge. It is estimated that over the long term, the number of gig jobs in India could reach 90 million, with total transactions valued at more than $250 billion. These are the strong foundations India must base its economic recovery on, especially at a time when the world is preparing itself to coexist with COVID-19. And while the path to this recovery will be peppered with hurdles, India has a rare chance to depart from conventional strategies to drive growth through digitalisation and platformization.

Below, I’ll explore why India must turn to platform jobs – powered by accelerating digitalisation – to facilitate the mammoth task of rebuilding its economy, and discuss what that process will mean for platforms themselves, adjacent sectors like financial inclusion and the broader economy.

How platform jobs drive economic growth and employment in India

The pandemic-fueled fluctuations in India’s economic growth rate projections have not been promising. According to the International Monetary Fund, the estimated growth rate for fiscal year 2022, calculated before the second wave of COVID-19, was 12.5%. After the devastation of the Delta variant, the revised figure came down to 9.5%. One of the key factors behind this economic slowdown has been dwindling demand, which can be attributed to mobility restrictions, weak consumer sentiment, and lower expenditure on non-essential goods and services, among other issues. Add to these the colossal loss of livelihood among the country’s 384 million informal workers, and demand is expected to plummet further. Therefore, what the economy needs is a robust recovery plan, strong enough to counteract the effects of the pandemic for years to come – and to provide enough employment for Indian workers to rebuild their lives and livelihoods.

There have been some signs of recovery in the country’s unemployment rate, which had risen to a post-1991 high of 23.5% in April 2020, but now stands at 7.24% (as of the beginning of December). To build on this momentum, India can look towards the platform economy to propel job creation. A Boston Consulting Group study has estimated that around 12 million jobs servicing household demand in India could potentially be done by gig workers. Further, it found that the gig economy could create approximately 1 million new jobs over the next couple of years alone.

The government’s Economic Survey 2020-21 highlighted that India has emerged as one of the world’s largest countries for flexi-staffing (i.e., gig and platform work), and that this work will likely continue to grow due to the influx of e-commerce platforms amid the pandemic. This growth will also be powered by the ongoing Fourth Industrial Revolution, in which accelerating digitalisation will drive greater entrepreneurship, which is the essence of the platform economy.

In our report, “Unlocking Jobs in the Platform Economy: Propelling India’s Post-Covid Recovery,” Ola Mobility Institute (OMI) analyses large-scale primary data from the mobility sector (i.e., both platform and non-platform drivers) to show how platforms can expand employment opportunities for all – and even offer new livelihood avenues to workers already engaged in the informal sector. The report highlights how platform companies today act as a facilitator for small businesses and the self-employed. Thus, platformization can unlock market access, nurture microentrepreneurship and even promote self-employment, especially among women. Platform jobs not only offer greater flexibility in hours but also have low entry barriers, giving workers the option to hold multiple jobs and thereby expanding their income.

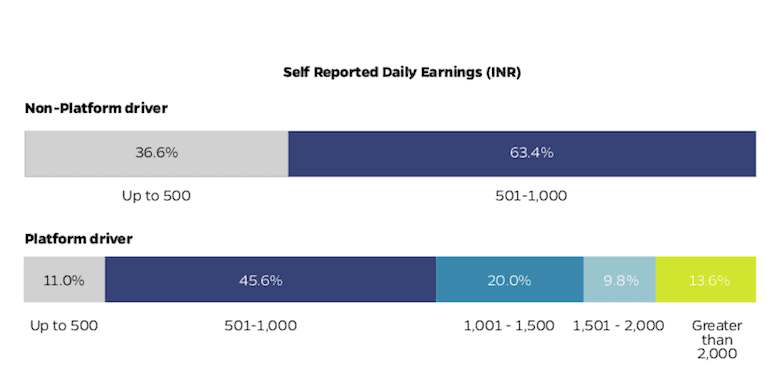

OMI’s study also found that platforms increase the earning potential of the labour force through higher discoverability and visibility. For instance, none of the 1,700 non-platform drivers we surveyed reported earning more than Rs 1,000 per day. On the other hand, among the 3,300 platform drivers we spoke to, around 57% earned up to Rs 1,000 a day and the remaining 43% earned even more (see Chart 1 below). And in addition to boosting workers’ earning potential, platform work offers them a clearly defined role and provides greater reliability of payments, which accelerates the restructuring of the labour markets away from informality.

Chart 1: Daily earnings reported by non-platform and platform drivers

Further, OMI’s survey indicated that platform drivers are likely to continue on their track of work longer than other mobility workers. Around 78% of platform drivers were satisfied with their work, as opposed to 69% of non-platform drivers. Moreover, in the study, drivers aged 26 – 45 accounted for 36% of the control group (non-platform) and 74% of the experiment group (platform), which also indicates a greater preference for ride-sharing platform work among the youth. These findings suggest that platformization could help India’s developing economy – which includes more than 400 million millennials – to truly tap its younger demographic, while building a resilient and inclusive future.

Digitalisation, assets and financial inclusion

Beyond employment, platformization can also help address another daunting challenge for India: The country has one of the largest unbanked populations in the world. Government programs like Jan Dhan Yojana have pushed for the opening of more bank accounts to increase access to financial services, but many of these accounts have remained underutilised or inoperative.

Still, the government’s financial inclusion efforts had been making strides in the digitalisation of financial services – but it is the COVID-19 pandemic which has truly catalysed this shift, by spurring contactless payments in economic activities ranging from online grocery shopping to bill payments. With frequent lockdowns restricting movement, the use of mobile wallets, the Unified Payments Interface and QR codes have emerged as safer and more convenient modes of payment, as they enable physical distancing and avoid possible transmission caused by the exchange of cash.

This is an opportune moment for the government to ride on the momentum of accelerated digitalisation and to build a more financially inclusive economy. Here, a push for platformization is key – not only in creating more jobs but also in ensuring workers’ equitable access to a full range of economic activities and banking facilities, which would create a safety net that the country’s informal workforce lacks. To that end, many platform jobs today provide benefits ranging from safety on the job through no-contact protocols and regular temperature checks, to accident insurance cover and assurance of pay – i.e., many platforms offer a minimum assured income for a set duration in case a worker tests positive for COVID-19. Additionally, platforms offer flexible work schedules and less dependence on a static workspace – benefits that are particularly important to women, who are often constrained by social norms that require them to be home to care for family members for much of the day. This increases women’s financial autonomy and improves their overall social status as well.

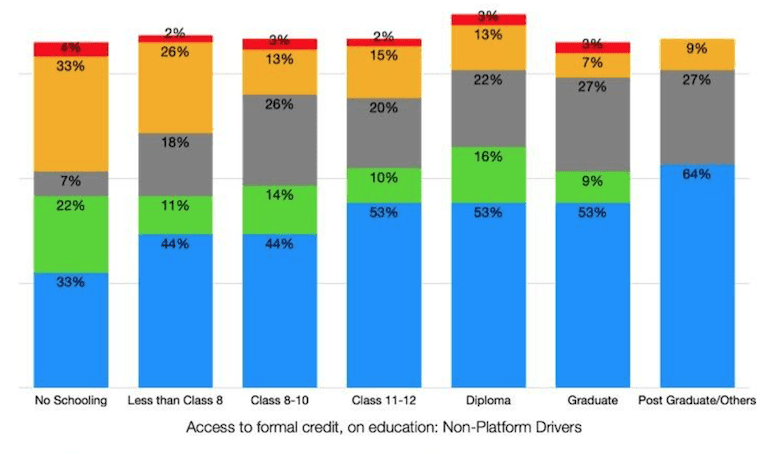

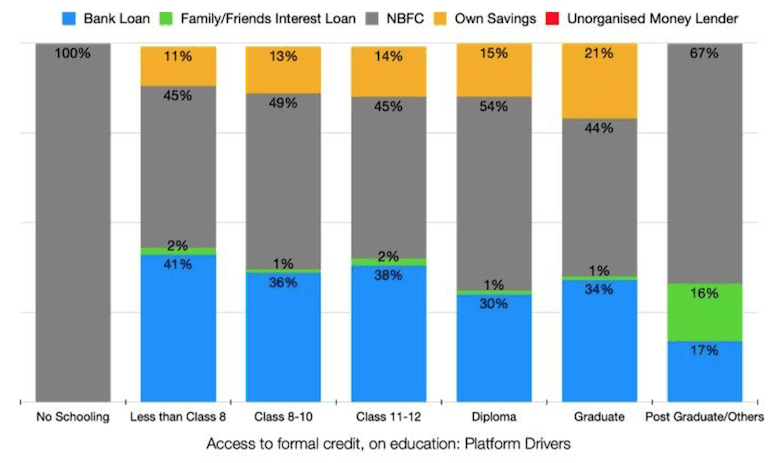

Supporting the growth of platformization can also have other positive impacts. OMI’s report indicates, as illustrated in Charts 2 and 3 below, that access to formal credit is higher for platform drivers across most education levels, with Non-Banking Financial Company (NBFC) and bank loans being the prevalent credit option. For instance, a platform driver with a diploma is more likely to access formal credit options compared to their non-platform counterparts with the same level of education – who may opt for unorganised money lenders or loans through friends/family. One possible reason for this difference is that ride-sharing platforms often partner with vehicle financiers who provide their drivers with easier and more affordable access to credit to purchase vehicles, thus bringing them into the formal banking system. Greater access to credit also resulted in the average age of asset owners in this group being much younger than in the non-platform driver group. This suggests that the platform economy is creating an emergent class of asset owners. As highlighted in the report, around 62% of platform drivers own their vehicular assets, as opposed to 51% of non-platform drivers.

Chart 2

Chart 3

Furthermore, in our white paper, “Asset Ownership in the Indian Economy: Contesting Traditional Conceptions,” OMI makes a case for the platform economy’s potential to increase the ease of converting an asset into productive capital. This can be instrumental in increasing the financial inclusion of those who may otherwise not be able to access credit opportunities due to their lack of a strong credit history or suitable collateral. Platforms across the mobility, real estate and delivery sectors have given individuals the opportunity to leverage their assets for economic gains. Thus, platformization through asset utilisation can improve the economic condition of a household, while also granting them credit access in the long run.

Platformization as the foundation for India’s digital future

Platforms are at the heart of India’s digital revolution, and they are driving the country’s business, investment and economic landscape today. Platformization can not only pave the way for India’s economic recovery from COVID-19, it offers an opportunity for the country to rebuild a more resilient and inclusive economy in the longer term. Over the last couple of years, the government has laid a strong foundation for the country’s digital development, through its efforts to expand financial inclusion and digital empowerment, with the Jan Dhan Yojana-Aadhaar-Mobile trinity spearheading these efforts. The next step would be to create an enabling ecosystem for fintechs that create tailored financial products for platform workers, through regulatory measures and revamping the national credit policy to find alternatives to traditional collateral. For instance, products such as microloans backed by cash flows and short-term, interest-free small loans backed by income-earning assets can create greater financial inclusion, ensure maximum asset utilisation, and facilitate a more equitable and participatory economy.

Additionally, the government itself could ease credit access to platform workers for the purchase of income-earning assets, by recognising platform assets under Priority Sector Lending policies. Taking it a step further, the national Emergency Credit Line Guarantee Scheme could be extended to cover platform workers, allowing them to access loans backed by their income-earning assets. This program, introduced in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis, enables banks and NBFCs to extend emergency credit facilities to business entities to meet their additional capital requirements. The government has already made some key moves towards supporting the platform economy, by becoming one of the first in the world to acknowledge gig and platform workers (through the Code on Social Security 2020) outside of traditional employment relations. This landmark legislation mandates social protection for all, regardless of their employment status, thereby catapulting India’s labour governance into the 21st century. The government could now focus on operationalising the Code by diffusing technology through all the stages of existing programs, to enable greater digital access among the country’s platform workers.

The pandemic has battered economies around the globe, and the subcontinent has been no exception. But unlike most other countries, India happens to have one of the largest numbers of gig workers in the world. If digitalisation can be leveraged to provide these workers with the tools for greater success, it can change the trajectory of the country’s economic recovery, while preparing its workforce to weather the challenges and embrace the opportunities of a digital future.

Chhavi Banswal is a Research and Advocacy lead at Ola Mobility Institute.

Photo courtesy of JanetandPhil

- Categories

- Finance, Technology