Launching India’s Microinsurance Revolution: How the Sector Can Build Upon Growing Customer Awareness Due to COVID-19

In the developed world, insurance is a part of life. But in the developing world, coverage has long been patchy and woefully inadequate. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has been a game changer for awareness of microinsurance in low- and middle-income countries: In India, for instance, the general public now understands its relevance to their lives. Though uptake has traditionally been low in the country, this increased understanding of insurance’s benefits is expected to spur greater demand for it. What was once widely seen as a luxury by the poor is increasingly seen as a necessity. As a result, India is now poised to experience a microinsurance revolution.

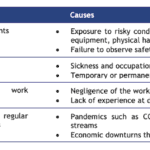

This long-awaited development could have a major impact on the poor. Low-income people live on the edge, just one misfortune away from disaster. Without a financial cushion, any injury, illness or natural disaster can deplete their meager resources and push them deeper into poverty — and their lives are full of potential risks. These communities are particularly vulnerable to perils both individual (illness, theft, unemployment, etc.) and economy-wide (drought, recession, etc.).

One of the most challenging risks involves health-related expenditures: Not only are there steep medical costs involved in a health episode, but there are also incidental expenses, like the cost of transportation to and from the hospital and meals purchased while away from home. This is further compounded by the loss of income during the period an individual is ill/injured or caring for an ailing loved one. Without insurance, people often turn to informal means to manage these risks, like cash savings, rotating savings and credit associations, and moneylenders — but such strategies provide inadequate protection. So when misfortune strikes, many get drawn into debt traps as they borrow beyond their means. This can lead them to sell productive assets, take children out of school or put them to work, compromise on food, or leave other illnesses untreated. Due to this dynamic, a health issue can easily become a financial sinkhole, especially for village women, who are often forced to drop out of the labor force, as they provide most of the care.

This can be an issue even for people with insurance. Health insurance policies in India typically don’t cover outpatient or domiciliary treatment, where the major expenses involve pharmacy bills, diagnostic tests, etc. Several health insurance programs cover wage loss on account of illness or other health-related issues, but many don’t. Due to these coverage gaps, even insured beneficiaries can incur high indirect costs — especially in cases that require hospitalization. For instance, India’s flagship public health insurance scheme, Ayushman Bharat, fails to recognize and compensate the indirect costs associated with hospitalization — and these are quite significant for the poor. They may be forced to avoid or delay treatment, as they cannot afford to lose their wages. Similarly, those who need longer-term hospitalization may go back to work even if they have not fully recovered.

Is Microinsurance the Solution?

Even with these coverage gaps, insurance would seem to present an obvious solution to many of the risk-management challenges faced by the poor — but providing coverage can be easier said than done. The poor usually face two types of risks, idiosyncratic (in which a loss is specific to a household) and covariate (in which the entire community suffers a loss — for example, from droughts and epidemics). From the insurer’s perspective, insurance coverage is most easily offered if risks within the relevant population are not covariate — so that only some people put in a claim at the same time, avoiding the massive payouts required by large-scale events. Furthermore, insurance for infrequent events like natural calamities is also typically more difficult to offer, in part because it can be hard to make assessments of damage in remote geographies.

In light of these challenges, the insurance industry doesn’t generally consider low-income communities to be “insurable” by standard schemes, whose premiums these customers can rarely afford. They need insurance schemes designed specifically for them. That’s why microinsurance has emerged as an alternative to provide protection to the bottom tier of the population.

A typical microinsurance scheme in India covers any insurable risk, including death, illness, accident, property damage, unemployment, crop failure and loss of livestock. These policies can secure vulnerable communities’ access to finance for both preventive health services and treatment. And they can distribute the costs of those services — and other unexpected expenses — over time, protecting against potentially devastating economic shocks. In this way, insurance coverage for life, health, accidents and more can give millions of low-income people a vital safety net.

Since the cost of insuring against an unforeseen development is considerably lower than self-insuring through savings, microinsurance can enable people to generate more income, raise school attendance rates, and even help pull themselves and their families out of poverty. It’s also a viable business model from the provider’s perspective because it leverages economies of scale through large volumes of small policies. Due to its affordability, more people can get policies, and more policies mean greater business for the company — and more coverage for clients. Just as poverty and vulnerability reinforce each other in a downward spiral, insurance protection can help perpetuate a virtuous circle, in which a thriving market boosts overall coverage by drawing in more providers.

Challenges in Microinsurance

As a result of these benefits, governments, donors, social businesses and other development actors engaged in combating poverty and designing social protection measures should view microinsurance as a key component of their toolbox. However, microinsurance accounted for less than 1.8% (for life) and 1.16% (for general insurance, including illness, accident, property damage, unemployment, natural disasters, etc.) in India’s broader insurance market in 2019-20. The reasons for the slow growth of microinsurance in the country include a long-standing lack of customer awareness and understanding of insurance, an absence of need-based products customized to the low-income segment, and cumbersome claims processes and procedures requiring extensive documentation and delays in disbursing claims. Because of these issues and the failure of insurers and other institutions to properly guide them, people often buy insurance policies without proper planning, then give up before they’re able to use their coverage because they don’t have money to pay the premium, or because of the difficulty of navigating the claims process. Yet despite this awareness-driven issue, client educational outreach from insurance companies has remained very limited — an issue the industry must address.

For the poor to reap the real benefits of microinsurance, insurance companies also need to function with a sense of responsibility when it comes to sales. Aggressive sales tactics prevent insurance agents from properly assessing the consistency of customers’ income streams when pitching their policies. As a result, customers often end up skipping a premium payment, which results in the suspension of their policy. Renewing coverage after a missed payment is cumbersome and involves harsh financial penalties, excluding many of the customers who are most in need of support. The greatest challenge for microinsurance schemes is to strike the right balance between adequate protection and affordability, to deliver real value to the insured.

This raises another key challenge: the high cost of selling and administering insurance. Microinsurance is a “low ticket” business, requiring huge volumes to become sustainable. But these volumes are hard to attain in countries like India, as the poor generally live off the banking grid, with families scattered across often-isolated rural areas. This makes physical access difficult and further increases costs, which are hard to pass on to consumers without pricing them out of the market. The transaction costs of issuing millions of small policies through service agents are also high. As a result, despite the potential of insurance products, uptake of microinsurance at market prices is extremely low, and it has not been easy to scale — except when heavily subsidized by the government.

India also lacks the distribution channels appropriate for lower-income groups, like networks of bank or insurance company branches. And there are additional problems with product design: Typically, rural insurance products are clones of products introduced in urban areas, which are not suited to the rural context. The complexity of customers’ lives and problems also makes underwriting and claim processing and resolution challenging.

Maximizing the Potential of Microinsurance

Despite their complexity, these challenges do have solutions. Rapid advances in digital payment systems are creating opportunities to connect poor Indian households to affordable and reliable financial tools, through mobile phones and other digital interfaces. Insurance coverage can be widened by coupling services with existing mobile financial products or creating new mobile solutions that bring insurance services straight to a consumer’s phone. In that way, insurance can piggyback on the exploding reach of mobile banking.

To further accelerate the expansion of microinsurance in the country, a committee at India’s Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority has suggested reducing the entry-level capital requirement for standalone microinsurance companies to INR 200 million from the current INR 1 billion. This entry barrier has typically been kept high to ensure that only the most financially sound providers enter this market, which protects the stability of the financial system. By lowering it, the government hopes to allow more providers to make the upfront investment in back-office technology for efficient premium collection and claims processing — a necessary component of successful implementation for a microinsurance scheme. To build on this progress, regulators should allow microinsurance companies (as well as cooperatives and mutuals) to act as composite insurers to offer both life and non-life policies through a single entity, boosting efficiency and lowering costs. Their portfolios should have a balance of both life and non-life business.

Other countries have witnessed large improvements in the design and availability of a range of insurance products. For instance, microinsurance products tailored for the farming community — such as crop and health/accident insurance, and coverage for irrigation systems, animal carts, aquaculture and cattle — are now available in the market. There are even niche products, such as insurance for snake bites, livestock welfare, failed wells, damage caused by thunderstorms, funerals and even unexpected expenses like the birth of twins. India’s insurance industry would do well to embrace a similar culture of innovation.

Microinsurance is now acknowledged as a highly effective tool to end the cycle of poverty. If the poor know that they are covered, they are more likely to invest in expanding businesses, diversify their crops or send their children to school — without the fear of losing their savings if something were to happen. Backed by this newfound sense of security, their willingness to take manageable risks in pursuit of new opportunities completely changes. Expanding microinsurance’s benefits to more vulnerable communities can have a vast impact on India’s anti-poverty efforts — and customers who’ve experienced the COVID-19 crisis have perhaps never been more receptive to embracing these benefits. If the microinsurance industry can capitalize on this opportunity, it could deliver something that previous generations in India could never imagine: the confidence to plan for the future.

Moin Qazi is an author, researcher and development professional who has spent four decades in the development sector.

Photo courtesy of DFID – UK Department for International Development.

- Categories

- Coronavirus, Health Care