Innovations for Transparency: Disruptive Technology Enters the Carbon Offsetting Space

Carbon offsets allow a net-positive emitter in one part of the world to pay a net-negative emitter in another part of the world to offset their emissions. The two trade a carbon credit, representing one tonne of carbon dioxide or an equivalent greenhouse gas, which is then retired upon transaction. As a result, the net-negative and net-positive impacts are cancelled out, resulting in “net-zero” emissions.

In theory, this system should help the world account for the unavoidable greenhouse gasses it emits in the transition to a low-carbon economy. In practice, the results are more contentious. With reports of projects not actually delivering the emissions reductions claimed, many have begun to distrust offsets. Moreover, as countries work toward the emissions reductions targets they set for themselves in the Paris Agreement, there is concern over double counting. This would occur if the country selling emissions reductions counts these reductions towards its own emissions targets, while the emissions-buying country also counts the same emissions reductions towards its targets.

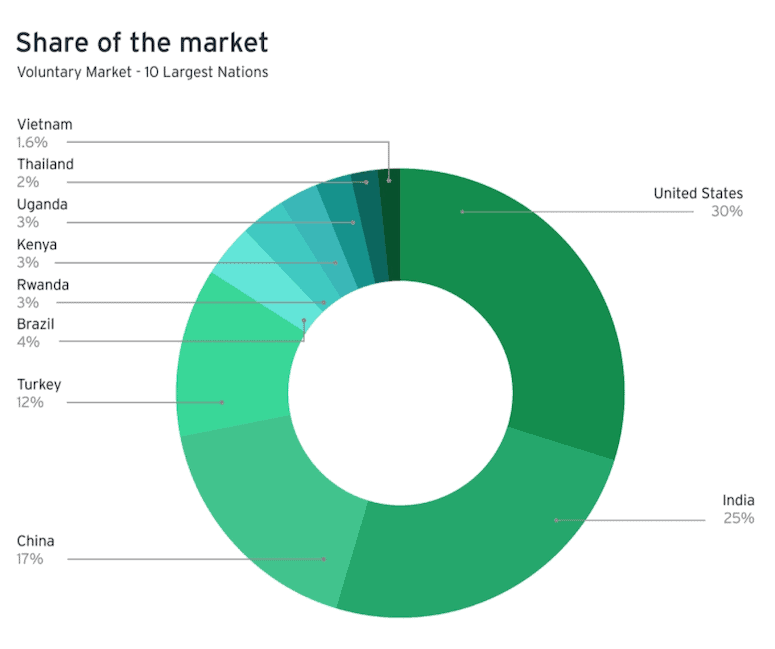

Data: AlliedOffsets

This is going to become an increasingly pertinent issue. In the past, the original carbon market set up by the U.N. (the Clean Development Mechanism) only allowed developing nations to produce offsetting projects and sell credits. The legacy of this can be seen in the graphic above, which shows that nine of the 10 largest nations producing offsets are in the developing world. The United States’ position there is indicative of changes we’re likely to see in the future. The U.S. opted to produce its own carbon markets, and as such sits as the largest offsetter in the voluntary market. As any nation is allowed to produce and sell offsets under the Paris Agreement, we are going to see a more diverse and larger set of offsetters. This is good for the environment if the credits do as suggested and are counted properly – but if there are any cracks in the system, then the increased stress from incoming market participants will serve to exacerbate this. These problems have created a gap in the market for firms which can deliver projects that guarantee trust and transparency.

The following innovative technologies and methods are being employed by new entrants to help address these problems and push the market forward.

Machine Learning in Carbon Offsetting

Machine learning is one particular application of artificial intelligence (AI). It enables systems to learn and improve based on experience and interaction, without needing to be continuously managed. It is an incredibly powerful approach for analyzing large amounts of data.

Machine learning can be applied to satellite imagery and sensors. Satellites provide an extraordinary amount of data to be processed. Without machine learning it would either require lengthy processing periods or lots of people to analyze this information, costing significant time or money. With machine learning, companies are able to efficiently and affordably work through the data. On top of this, some are also employing LiDAR technology. This is a method that measures spatial dimensions, like distance, by illuminating a target with a laser. This creates powerful real-time computer images of the environment, allowing firms to understand whether (for example) forestry and afforestation projects are delivering on their promises.

Two companies currently employing this technology for carbon offsetting are Sylvera and Pachama. Sylvera uses machine learning and satellite data to track carbon offsetting projects and monitor their performance. It supports both the purchasers of carbon credits and the project developers (i.e.: those who originate and run the projects that produce these carbon credits, generating revenue by selling them). More specifically, Sylvera ensures that the projects behind the offsets are delivering what they claim. It combines machine learning with satellite data, enabling it to refresh its data on a regular basis, improving on current carbon verification practices. Moreover, Sylvera can integrate its data into the internal reporting of companies looking to offset their emissions, to facilitate their carbon accounting practices. Projects that work with Sylvera benefit from the transparency they gain. This restores trust in the market, encouraging more demand.

Pachama also uses machine learning and satellite imaging. It applies this technology to look at how carbon is being stored within the biosphere, in particular around forests. Its use of LiDAR helps create 3D visualisations of the real-time impact of forests on CO2 absorption and release.

Big Data and Natural Language Processing

The term “big data” is often applied to any large set of data, whether structured or unstructured, that grows over time. The carbon offsetting industry, from project developers to brokers and resellers, creates huge amounts of data – often hundreds or thousands of pages of verification reports per project. This creates a problem: How can projects extract, structure and analyze this data?

Natural language processing (NLP) is an application of AI that can help analyze large chunks of text. In NLP, the computer is trained to understand language, enabling it to perform powerful analysis of written text at scale, identifying patterns and generating insights.

At AlliedCrowds we have entered the carbon offsetting space to employ these disruptive technologies, with the aim of bringing more transparency to the industry. Our company is using big data and will soon begin using NLP for our AlliedOffsets database and directory. AlliedOffets is a new database that is the first of its kind in the offsetting market. It uses web scraping tools to aggregate an open database of carbon projects in the voluntary offsetting market. It hosts data on the registries where projects register and verify their offset carbon emissions, including the four largest voluntary registries (American Carbon Registry, Climate Action Reserve, Gold Standard and Verra), along with the U.N.’s own registry, the Clean Development Mechanism. Through the AlliedOffets platform, purchasers and sellers are able to filter for projects by country, project type and registry. The platform also includes an interactive data dashboard to improve macro-level visualisations of the industry.

We are also beginning to introduce NLP into our work. Through this we will be able to extract valuable data from project documents, clarifying important details about the carbon offsetting projects – such as who actually verifies and monitors whether these projects are delivering the emissions reductions they claim. Whether or not projects are creating emissions reductions is at the crux of offsettings’ dubious status: With NLP we hope to take the market one step closer to answering this question, discerning genuinely additional projects from those that aren’t.

The goal of AlliedOffsets is to provide real transparency and greater access to information for those looking to better understand the carbon offsetting space.

Using Blockchain to Enhance Carbon Offsetting Transparency

Blockchain is a distributed ledger technology that allows information to be recorded by a set of distributed users across the system. Blockchain’s approach contrasts with traditional accounting methods, in which data is typically stored in a central hub that every user has to interact with. In blockchain, each user can enter new information to the ledger, which copies and distributes that information across a network of computers, giving all users instant access to it and showing which user added it to the ledger. The mechanism by which data enters and is accepted by the blockchain makes it virtually impossible to change or hack. Many see this as an exciting technological application for offsetting due to its transparency and integrity. With transactions conducted on a blockchain, users could be confident that their carbon credit wasn’t being double-counted, or resold after it has already been used. There are a number of firms exploring the use of blockchain for carbon offsetting, including Climatetrade and Everledger.

Climatetrade hosts a carbon offsetting marketplace that is based on a distributed ledger technology. This system inherently builds transparency and full traceability into the transactions, offering security against double counting a project’s emissions reductions. Along with hosting carbon offsetting projects on a blockchain, Climatetrade develops sustainability reports for its clients. This application’s value will continue to rise, as companies’ carbon footprints are increasingly scrutinised and (potentially) become the subject of carbon taxes.

Everledger didn’t start out as a carbon offsetting platform. Instead, the firm developed a blockchain platform to track and confirm the transfer of luxury goods, such as gemstones. However, it is now using this technology to enable industries to calculate their carbon emissions data throughout their supply chains, and to transparently offset these emissions through the platform. Everledger’s move into carbon offsetting as a second business model shouldn’t be ignored. As one of the first non-offsetting companies to enter this sector, it has paved the way for other businesses to embrace the financial value of carbon offsetting. In turn, we can expect to see demand for these offsets rise, with income flowing predominantly to emerging markets.

Taking Carbon Offsetting Directly to Consumers

Consumer product firms are not employing the emergent technologies discussed above, but are instead applying existing technologies and business models to a new market — taking carbon offsetting directly to consumers.

Seeds, which is currently in the pre-launch phase, is enabling users to invest the spare change from online payments into renewable energy projects. For example, an individual may spend $8.50 on a new book, and the 50 cents in change would automatically be allocated towards a carbon offsetting technology. Users have full choice of the kind of renewable energy project they want to invest in, and how much spare change can be used when they make purchases. This is a peer-to-peer lending practice which connects individual lenders with renewable energy projects that need funding, allowing these projects to avoid the heavy fees charged by traditional financing institutions. This model will enable many carbon offsetting projects to come into existence that were previously considered too risky.

Climeworks is incorporating a subscription model into its carbon offsetting business — instead of signing up to receive regular delivery of groceries or other consumer goods, users subscribe to remove carbon from the atmosphere via Climeworks’ offsetting projects. Importantly, Climeworks is directly selling its credits to customers, rather than going through the lengthy and expensive process of having its work verified in order to register them with the major voluntary offsetting registries. Buying credits straight from the project developer responsible for creating them is a big selling point for customers who are disenchanted with buying carbon credits from big registries and resellers, whose credits feel impossible to track and trace.

Conclusion

Carbon offsetting is currently in the midst of a dramatic change. In the run-up to new international policy that will kick in with the end of the Kyoto Protocol and incoming commitments from COP26, new and established firms are employing emergent technologies and disruptive business models to tackle the systemic problems that have hampered the industry. The outcomes of these innovations are likely to improve the quality of carbon reductions, deliver more capital where it’s needed most in emerging markets, and support a more transparent international carbon trading system.

Kavit Borkhataria is an Alternative Finance Analyst at AlliedCrowds.

Photo courtesy of mad mags.

- Categories

- Environment, Technology