The Power of Local Women: An Innovative Social Capital Model Addresses Rural Financial Inclusion in India During COVID-19

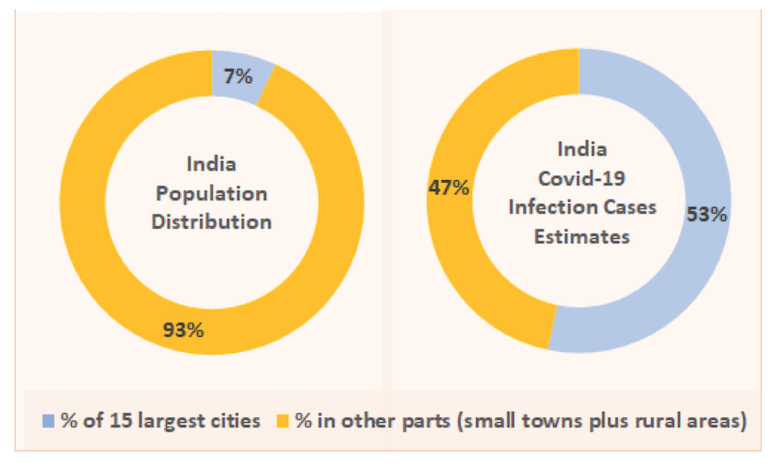

Socio-economic life plummeted to a near-standstill in India as the COVID-19 lockdown unfolded in March. Since then, it hasn’t fully recovered – in part because the relaxations in the lockdown are only partial, and many regions have re-instated lockdowns in response to newly rising infection rates. The distribution of COVID cases suggests that rural regions (and small towns) have fared better than their big-city counterparts. For instance, based on the population of India’s 15 largest cities, their infection tally as reported in the latest news articles, and the overall case count from the government’s COVID-19 website, the country’s largest 15 cities – which comprised only around 7% of India’s population in the last Census in 2011 – have contributed over half of the country’s COVID-19 infection cases so far.

Sources: Census 2011 data, latest news articles on city-wide infection and Indian government’s COVID website

Nevertheless, the pandemic and its economic impact have had a heavy toll in rural India. To help these local communities weather the crisis, the Indian government has transferred funds into women’s Jan Dhan bank accounts. Jan Dhan, or people’s asset, is a financial inclusion programme launched by the Modi government to open accounts for poor and marginalised families who were generally outside the formal banking sector. The government is now using these bank accounts as a channel to transfer cash grants to the people whose daily wages have been the worst affected by the COVID-19 lockdown. However, in assessing the likely impact of these transfers, some rural-specific issues spring up. Amongst them are the logistics involved for the rural populace to access those funds, as the nearest ATMs or bank branches are often several kilometres away, which can require long journeys without any public transport. This presents a significant opportunity cost, even under normal circumstances, for lower-income rural families who have to take time away from working for their daily livelihoods. What’s more, many rural women still face restrictions on mobility, and the lockdown has made it even tougher for them to access government support funds when they need them the most. Further complicating this picture, the long queues outside bank branches can also compromise the public health gains made from an otherwise stringent lockdown, exposing more people to the virus.

A Lifeline for Rural Communities During COVID-19

To address these issues, the social impact organisation Grameen Foundation and its subsidiary, Grameen Foundation India have created the Grameen Mitra model (Grameen means rural and Mitra means friend). This model has provided a lifeline for rural women and communities in Maharashtra’s Bhandara district. It is an initiative of Grameen’s Women-Link project in Bhandara, which is involved in educating local communities on digital financial literacy, banking modules and goal-based financial planning. Scaled up with the goal of bringing financial inclusion to far-flung rural areas by leveraging digital technologies, this model is helping the local communities in the villages of Bhandara weather the COVID-19 lockdown.

Grameen Mitra is a network of village-based women which, even prior to COVID, was helping local villagers access basic banking services like cash deposit, withdrawal and balance checks from their own communities by using Aadhaar-linked biometric devices. (Aadhaar is a biometric identity system that includes a unique identification number and a national ID card for every Indian citizen, which is linked to bank and tax accounts to create transparency in income flows and curtail tax evasion and counterfeiting.) Grameen Mitra leverages Aadhaar and the Grameen Connect mobile application to enable digital payments in rural villages. The network of Mitra women act as agents of positive change by helping villagers circumvent the logistical issues involved in travelling to faraway ATMs or bank branches. Many of the beneficiaries are also local women, and the network also targets villagers who are elderly, disabled or pregnant. With the COVID-19 lockdown reducing access the banks, this services provided by these women have become all the more relevant.

Cash withdrawals through the Grameen Mitra network have enabled farmers, pensioners and households to access the balance in their bank accounts and meet their cash needs – whether the money comes from income, pensions, transfers from family/friends, or the government cash grants intended to help them through the pandemic. Thus it is helping to ensure that the basic socio-economic engine in these villages keeps running, to the best extent possible, during the lockdown. This network of Mitra women has also helped spread awareness of the health and safety measures that have been implemented in response to the pandemic, by educating customers about the need for social distancing, mask usage and hand-washing, both during their visit to the Mitra and at all other times in their daily lives. The Mitra women are also mandated to refuse service to any customer who does not adhere to these guidelines.

Challenges and Benefits of the Grameen Mitra Model

Initiating this social capital model has had its challenges. The Grameen Mitra women live in the local villages where they provide services, and many households in these communities are still patriarchal in nature, offering limited opportunities for their women to venture out to work. Thus, it took several conversations to effect behavioural changes in those families, increasing the time required to onboard the Mitra women into the network. But including these local women in the model has also had an upside. They have personal relationships and trust within their communities, which became the assets the model was built on. Since bank transactions like cash withdrawals involve some lag time for clearing, this trust factor works both ways. It makes it easier for the beneficiaries to approach the Mitra women for services like withdrawals, balance checks and payment of utilities, but it also allows the women to offer a different level of personal support. For instance, in one case a beneficiary needed a small cash loan for an immediate emergency, which the Mitra woman paid upfront from her own account – thanks to the existing trust in the relationship, she knew the recipient would repay it after a couple of days, once their government payment had been cleared and credited by the bank.

The Grameen Mitra model not only helps increase the financial independence of rural women and other vulnerable people by building on the social capital within their own local communities, it has also proven instrumental in overcoming cash constraints and ensuring access to basic banking services during unexpected crises like the lockdown. To give an indication of how essential these services have been during COVID-19, the average weekly withdrawals per Mitra woman was Rs 3000-5000 before the lockdown. Those averages have risen over threefold to Rs 12000-15000 post-lockdown.

Models like these are easily scalable – not just in India but across other developing nations whose demographic and geographic profiles are similar. This is largely due to the emphasis on using digital technologies instead of the brick-and-mortar banking infrastructure, which is a major limiting factor in extending the bank branch network across the expanse of large nations. In addition, India’s efforts to develop its own digital payments infrastructure complement this approach. The model may also prove useful in facilitating other types of financial services: Research must be done to determine if networks like this can create near-term solutions to revive the microfinance sector, which has been negatively impacted by the lockdown’s logistical issues. In the long-term, models like these which promote greater financial inclusion can only help reduce the income inequality that exists between urban and rural geographies in emerging markets.

Prabhat Labh is CEO of Grameen Foundation India and Sourajit Aiyer is a research consultant with South Asia Fast Track Sustainability Communications.

Photo courtesy of sandeepachetan.com travel photography.

- Categories

- Coronavirus, Finance